Australia is at war with cats.

In an effort to control this non-native species’ impact on the environment, and in spite of impassioned pleas from Morrissey and Brigitte Bardot, the government has pledged to kill 2 million feral felines by 2020. Bardot wrote a letter to the continent’s environment minister, stating that, “This animal genocide is inhumane and ridiculous” because the 18 million cats that remain will simply keep on breeding. Sterilization, she argues, is a better long term solution. Maybe for the cats. But many feel the Australian ecosystem can’t afford to wait for such potent (yet potentially impotent) predators to die of old age.

In an effort to control this non-native species’ impact on the environment, and in spite of impassioned pleas from Morrissey and Brigitte Bardot, the government has pledged to kill 2 million feral felines by 2020. Bardot wrote a letter to the continent’s environment minister, stating that, “This animal genocide is inhumane and ridiculous” because the 18 million cats that remain will simply keep on breeding. Sterilization, she argues, is a better long term solution. Maybe for the cats. But many feel the Australian ecosystem can’t afford to wait for such potent (yet potentially impotent) predators to die of old age.

|

That’s because Australia’s crusade isn’t against invasive feral cats so much as it is for protecting endangered native species. The impact cats have on Australia’s environment is profound. Feral cats are the biggest threat to 124 species of endangered Australian mammals, birds, and lizards. It is estimated that a healthy adult cat will kill up to five times a day, and they are thought to be responsible for the extinction of at least 27 Australian mammals, including the lesser bilby, desert bandicoot and large-eared hopping mouse.

|

People who debate the ethics of blaming cats for being cats must acknowledge that humans in Australia share blame as well. This isn’t the first time Australians have had to deal with the environmental fallout of their animal importation habits. Australians have a history of inviting animal guests that don’t know when to leave. Some of these creatures – like goats (feral population of at least 2.6 million) and donkeys (with feral numbers of up to 5 million) – came with European colonizers as farm and work animals. Others, including the European rabbit (200 million now living wild) and the red fox (7.2 million) were brought in for sport. Australian farmers imported the cane toad (now at 200 million plus) to control a native species of beetle that threatened sugar plantations. Even the dingo – one of Australia’s most recognizable symbols – was brought to the continent by man, albeit some 4,000 years ago, though it’s no longer considered an invader.

Eastern Barred Bandicoot, Photo by J. Harrison, via Wikimedia Commons.

Eastern Barred Bandicoot, Photo by J. Harrison, via Wikimedia Commons.

Cats came to Australia as pets, with their presence down under first noted in the historical record in 1804. Reports of cats living wild in and around Sidney surfaced about 15 years later. Evolutionary biologists understand why it’s been so easy for cats to thrive in Australia, and why their impact has been so devastating to native species. A study published in 2012 by researchers from the University of New South Wales found that “the impact of alien predators on native prey populations is often attributed to prey naiveté towards a novel threat;” something they confirmed by examining the foraging habits of native bandicoots living in suburban areas. Researchers concluded that bandicoots were much more likely to avoid yards with resident dogs than yards with cats – probably due to the species’ 4000-plus years of experience with the dingo. Bandicoots have had enough time to recognize dogs as a threat – something their evolutionary arc has yet to teach them about cats.

Because bandicoots and other prey animals recognize dingoes as dangerous, dingoes can be considered native, as can other non-native species whose prey has adapted to their presence. Where this leaves wild Australian cats and their prey at present is unclear. There are those who argue that the key to sustaining biodiversity in Australia and other places on the planet rests not in returning biomes to how they once were, but in accepting them as they are – a train of thought which give cats a pass (pity the poor bilby).

It should be obvious by now that cats really aren’t the problem in Australia.

Humans are potent, if not skilled, manipulators of the natural world. For centuries we have been selectively breeding animals to promote desired physical and behavioral traits, but we’ve also been engaged in other forms of biological and environmental manipulation. We slash and burn jungles to make way for crops. We eliminate predators to allow livestock to thrive. We mine the earth to power our machines. We dredge the oceans so we may eat. And we bring cats to places they don’t belong because we like that weird kneading thing they do when they sit on our laps. To look at the earth as it is now is to recognize humanity's place as the ultimate invasive species.

In order to understand and manage the world we created, we need to first accept the fact that we did indeed create it. Man’s role as the primary driver of environmental change, while still denied by some, has prompted geologists to conclude the Earth has entered a new epoch: the Anthropocene. The name signifies the role mankind has had as the driving force of evolutionary change on lithospheric, atmospheric, and biospheric levels. In short, nature – in what we have imagined to be its purist form – no longer exists. It hasn't for a while. Consciously or not, humans have approached the Earth the way they have approached cats and other domesticated animals, implementing a form of “selective breeding” on a planetary scale.

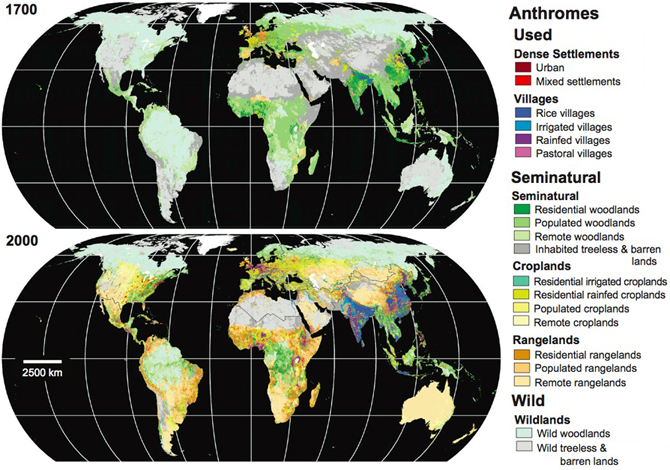

Ecologists Erle Ellis and Navin Ramankutty have documented the impact humans have had on the planet. Ellis and Ramankutty have reimagined those biome maps we saw in school so that instead of showing different types of habitats and the spaces they occupy, their maps reflect how humans interact with these spaces. These anthrospheric maps reflect a world as it is, where “biology goes on in a human context” and the natural cycle has come to be ruled by human activity. They make a compelling visual point.

Because bandicoots and other prey animals recognize dingoes as dangerous, dingoes can be considered native, as can other non-native species whose prey has adapted to their presence. Where this leaves wild Australian cats and their prey at present is unclear. There are those who argue that the key to sustaining biodiversity in Australia and other places on the planet rests not in returning biomes to how they once were, but in accepting them as they are – a train of thought which give cats a pass (pity the poor bilby).

It should be obvious by now that cats really aren’t the problem in Australia.

Humans are potent, if not skilled, manipulators of the natural world. For centuries we have been selectively breeding animals to promote desired physical and behavioral traits, but we’ve also been engaged in other forms of biological and environmental manipulation. We slash and burn jungles to make way for crops. We eliminate predators to allow livestock to thrive. We mine the earth to power our machines. We dredge the oceans so we may eat. And we bring cats to places they don’t belong because we like that weird kneading thing they do when they sit on our laps. To look at the earth as it is now is to recognize humanity's place as the ultimate invasive species.

In order to understand and manage the world we created, we need to first accept the fact that we did indeed create it. Man’s role as the primary driver of environmental change, while still denied by some, has prompted geologists to conclude the Earth has entered a new epoch: the Anthropocene. The name signifies the role mankind has had as the driving force of evolutionary change on lithospheric, atmospheric, and biospheric levels. In short, nature – in what we have imagined to be its purist form – no longer exists. It hasn't for a while. Consciously or not, humans have approached the Earth the way they have approached cats and other domesticated animals, implementing a form of “selective breeding” on a planetary scale.

Ecologists Erle Ellis and Navin Ramankutty have documented the impact humans have had on the planet. Ellis and Ramankutty have reimagined those biome maps we saw in school so that instead of showing different types of habitats and the spaces they occupy, their maps reflect how humans interact with these spaces. These anthrospheric maps reflect a world as it is, where “biology goes on in a human context” and the natural cycle has come to be ruled by human activity. They make a compelling visual point.

So what does this mean for Australia’s cats? Should they stay or should they go, now?

As it stands, the Australian government has no intention of altering its plan, meaning that at least 2-million cats who aren’t as fleet of foot as their brethren will die. That might not be a bad thing. Australia will never again be the land it was before the arrival of the domestic cat, or the red fox, or the cane toad, and even if it could be, we’d still be there. And humans, it seems, are incapable of keeping nature “wild.” Because of this, Ellis and others argue that it’s time for a new approach, something he calls “postnatural environmentalism.” He writes:

As it stands, the Australian government has no intention of altering its plan, meaning that at least 2-million cats who aren’t as fleet of foot as their brethren will die. That might not be a bad thing. Australia will never again be the land it was before the arrival of the domestic cat, or the red fox, or the cane toad, and even if it could be, we’d still be there. And humans, it seems, are incapable of keeping nature “wild.” Because of this, Ellis and others argue that it’s time for a new approach, something he calls “postnatural environmentalism.” He writes:

|

Postnaturalism is not about recycling your garbage, it is about making something good out of grandpa’s garbage and leaving the very best garbage for your grandchildren. Postnaturalism means loving and embracing our human nature, the nature we have created to feed ourselves, the nature we live in. What good is environmentalism if it makes you depressed about the future?

This is about recognizing that our farms, and even our backyards and cities, are the most important wildlife refuges in the world and should be managed as such. We can keep people out of places we want to think of as wild, but these places will still be changing because of global warming and the alien species we introduce without even trying. |

Don’t confuse postnaturalism with fatalism. It’s not that we can’t save the planet, we just can’t return it to its former glory – whatever that looked like. But we can accept our role in what Earth has become, and influence what it will be by reducing our carbon footprint, pushing for renewable energy, and maybe killing a few million cats (while saving a few ground parrots in the process).

Header image by T. Guzzio. Original photo by Mark Marathon via Wikimedia Commons.

CONNECT WITH TOM:

In addition to editing Prodigal's Chair, Tom is a teacher, father, husband, writer, artist, futbol fan and slightly maladjusted optimist. He likes birds, and lives in Beverly, Massachusetts with his wife and their two newly adopted cocker spaniels. You can connect with him on Twitter @t_guzzio, or via email at tom@prodigalschair.com.

ADD YOUR VOICE:

ABOUT COMMENTS:

At Prodigal's Chair, thoughtful, honest interaction with our readers is important to our site's success. That's why we use Disqus as our comment / moderation system. Yes, you will need to login to leave a comment - with either your existing Facebook, Twitter, or Google+ account - or you can create your own free Disqus account. We do this for a couple of reasons: 1) to discourage trolling, and 2) to discourage spamming. Please note that Disqus will never post anything to your social network accounts unless you authorize it to do so. Finally, if you prefer you can always email comments directly to us by clicking here.