During the latter part of the 1970s, a group of young, rebellious English musicians tried to change their prospects by creating an entirely new visual and musical aesthetic based on non-conformity to established values and authority. These artists became known as Punks, and they used their loud, grinding music, garish appearance and outlandish attitudes in an attempt to challenge the prevailing views of class, status and individual freedom. With names like The Clash, The Sex Pistols, Stiff Little Fingers, The Damned, and The Vibrators, Punk bands stood on the outside looking in, and tried to point out the contradictions inherent in modern English society. This article will explore how socio-economic factors led to the colored hair, quick chord changes, and obscene, cockneyed lyrics that set Punk apart from other musical forms, and kept it outside the established social order. But Punk was a movement that both confronted and embodied the contradictions it sought to rectify. Via relentless self promotion based on a “do-it-yourself” model, Punk created a dialectic that tried to subvert a system that allowed record executives to make a buck at the expense of working class kids who really couldn't afford to pay, and it ironically embraced this system as a means to deride it. Punk tried to become a resounding "no" to the demands of middle class values in a working class world, but its outsider image and its profound impact on British youth helped to establish Punk as a social movement while leading to its induction into the established social order, ultimately diffusing its power to promote lasting social change.

Punk served as a cultural platform for its many fans, which used it as a way of protesting the hardships and frustrations that came with being young, working class and British in the mid to late 1970s. Yet for these young fans, Punk was not the main event, rather "the main event was Britain herself: the virtual collapse of her economy, the wearying dissolution of her post-war affluence, the widening breach between her classes- her decline."(1) Punk began as an outgrowth of the deepening sense of hopelessness that grew from the troubling socio-economic condition of Britain in the 1970s. The economic boom of the 1950s, coupled with the rise of the popular youth culture of the 1960s, were both structurally conducive to the subsequent rise of Punk. These factors would combine with the economic hardships of the 1970s to produce enough structural stress to ensure that Punk had a receptive audience, and helped to spread the general perception among many British youth that Punk was a viable outlet with which to voice their frustrations. Punk created situations that further precipitated youth involvement, and that mobilized them into mass action. But Punk’s love-hate relationship with the recording industry would ultimately became an effective means of social control that diffused and deflected its emotionalism, and lead to its failure as a vehicle for real social change.

The conditions that were structurally conducive to the rise of Punk were actually rooted in the post World War II boom of the 1950s. With victory secure, England and her European allies turned their attention to rebuilding a broken continent. With unprecedented effort, both the liberal and conservative elements of the English government united to create a new, robust England out of the rubble of the old. By the time Clash member Mick Jones was born in 1955 the British economy was gaining strength. The united government had instituted social programs that successfully diffused unemployment, and working class youths were presented with better educational and professional opportunities than ever before. While all this growth was taking place, the care free, vibrant strains of a new sound floated over from America. As Britain came to grips with its post-war security, Rock and Roll music played in the background, becoming an appropriate soundtrack for a newly energized nation.

Punk served as a cultural platform for its many fans, which used it as a way of protesting the hardships and frustrations that came with being young, working class and British in the mid to late 1970s. Yet for these young fans, Punk was not the main event, rather "the main event was Britain herself: the virtual collapse of her economy, the wearying dissolution of her post-war affluence, the widening breach between her classes- her decline."(1) Punk began as an outgrowth of the deepening sense of hopelessness that grew from the troubling socio-economic condition of Britain in the 1970s. The economic boom of the 1950s, coupled with the rise of the popular youth culture of the 1960s, were both structurally conducive to the subsequent rise of Punk. These factors would combine with the economic hardships of the 1970s to produce enough structural stress to ensure that Punk had a receptive audience, and helped to spread the general perception among many British youth that Punk was a viable outlet with which to voice their frustrations. Punk created situations that further precipitated youth involvement, and that mobilized them into mass action. But Punk’s love-hate relationship with the recording industry would ultimately became an effective means of social control that diffused and deflected its emotionalism, and lead to its failure as a vehicle for real social change.

The conditions that were structurally conducive to the rise of Punk were actually rooted in the post World War II boom of the 1950s. With victory secure, England and her European allies turned their attention to rebuilding a broken continent. With unprecedented effort, both the liberal and conservative elements of the English government united to create a new, robust England out of the rubble of the old. By the time Clash member Mick Jones was born in 1955 the British economy was gaining strength. The united government had instituted social programs that successfully diffused unemployment, and working class youths were presented with better educational and professional opportunities than ever before. While all this growth was taking place, the care free, vibrant strains of a new sound floated over from America. As Britain came to grips with its post-war security, Rock and Roll music played in the background, becoming an appropriate soundtrack for a newly energized nation.

London's Carnaby Street circa 1968. Photo via the Victoria & Albert Museum.

London's Carnaby Street circa 1968. Photo via the Victoria & Albert Museum.

The placid prosperity of the 1950s would lead to choppy waters in the 1960s. Like their American counterparts, British youth were starting to use their newfound security and buying power as a platform to appraise the state of the nation as they saw it. Their education, coupled with the prosperity of their parents, gave them a voice that had previously been ignored, and made them a new and viable market with unique tastes and full wallets. This caused the Rock and Roll fad of the 50s to become a legitimate industry in the 60s, and at the same time gave British youth a sort of social power they never experienced. Rock and Roll broke down race and class barriers, and became an established voice for social change, as artists like The Beatles, The Who, and others began to question the nature of the English class system, British imperialism, and the threat of nuclear war. Their music reflected the concerns of their young audiences, and these groups became ambassadors of the new youth culture via the lyrical content of their music and the attention it received on a national scale. Despite the tension their actions caused, there was a sense among young people that they could change the world in a positive way, and make a good nation even better by ironing out the contradictions present in their prosperity. But as the Beatle’s encouraged their listeners to “Let it Be” recession set in. If all you needed was love in the 60s, all you had were bills in the 70s, for the cultural friction produced by the 60s youth culture gave way to economic strain early in the next decade that would precipitate the rise of Punk.

By 1976, England was in the grip of a deep recession marked by the highest unemployment rate since the Second World War, and social spending was cut by one billion pounds as legislators prepared an appeal to the International Monetary Fund for aid.(2) The pastel colored psychedelia that marked the hope and prosperity of post-war England was waning, and "the bright colors, the 'classlessness', and especially the optimism of the sixties, now seemed like a mirage."(2) There was a deep sense that the 60s promise of a better, more complete future might not be fulfilled, and patience with both the liberal and conservative elements of the government was wearing thin. This growing sense of frustration was spreading, and would be vividly captured by an anonymous vandal, who wrote on a dingy brick wall that bordered a working class neighborhood filled with dirty row-houses: "How many bridges do we have to cross before we get to meet the boss?"(2) This question, along with many others preoccupied many of the young men and women who lived in these neighborhoods, and would lead them to see Punk as a means to not only find the answers, but to be the boss. In this sense, Punk could be seen as a redemptive, norm oriented social movement that sought to provoke the individual to create a voice for themselves within the void left by economic and social decline in the din of a highly differentiated society.

By 1976, England was in the grip of a deep recession marked by the highest unemployment rate since the Second World War, and social spending was cut by one billion pounds as legislators prepared an appeal to the International Monetary Fund for aid.(2) The pastel colored psychedelia that marked the hope and prosperity of post-war England was waning, and "the bright colors, the 'classlessness', and especially the optimism of the sixties, now seemed like a mirage."(2) There was a deep sense that the 60s promise of a better, more complete future might not be fulfilled, and patience with both the liberal and conservative elements of the government was wearing thin. This growing sense of frustration was spreading, and would be vividly captured by an anonymous vandal, who wrote on a dingy brick wall that bordered a working class neighborhood filled with dirty row-houses: "How many bridges do we have to cross before we get to meet the boss?"(2) This question, along with many others preoccupied many of the young men and women who lived in these neighborhoods, and would lead them to see Punk as a means to not only find the answers, but to be the boss. In this sense, Punk could be seen as a redemptive, norm oriented social movement that sought to provoke the individual to create a voice for themselves within the void left by economic and social decline in the din of a highly differentiated society.

During this time, the English music industry was experiencing strain as well. For one thing, it was in a creative quandary. Business was controlled by six multi-national corporations who saw little sense in pouring money into developing new bands. K-Tel compilations of sixties one-hit-wonders, along with the Swedish bubble-gum pop group, Abba dominated the charts, while “the Bohemian, if not revolutionary attitudes of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones” were now co-opted and bankrolled by the aforementioned multi-nationals.(2) This lack of creative fervor, coupled with the recession led to declining album sales and the industry was worried. As one producer would complain, "It is certainly time we got a super new UK thing like The Beatles. The music business needs a shot in the arm. We are overdue for it."(3) Punk could’ve easily been that shot in the arm. But even though the timing seemed right for something new and different, many companies were unwilling to risk losing money on untested artists in such troubling economic waters. This would help Punk establish its outsider mystique because it started from the ground up with very little help from the music industry, and established a dedicated core of fans before any band could record a demo tape, let alone an album.

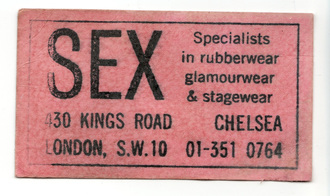

A business card from Sex, courtesy of Punk Pistol

A business card from Sex, courtesy of Punk Pistol

The trepidation on the part of many record companies could not overshadow the fact that change was needed, a belief that would spread and underpin Punk during its genesis. In the midst of these troubling economic conditions many disaffected youth began meeting in places like the clothing shop at number 430, King's Road in London where the perception that something wasn’t right was cultivated by its owner Malcolm McClaren. Simply called "SEX," this shop and others like it, provided a place where kids who had nothing else to do could kill time in surroundings they knew their parents wouldn’t approve of. These places, which sold outlandish clothes and the occasional record, became the foundations upon which Punk was to be built. Many of these shops catered to the unrest of their patrons, and would serve as epicenters for the growing network of kids that would become Punk’s adherents. But what set SEX apart from these other shops was the fact that McClaren had agreed to manage a band that some of the teen aged shop regulars had assembled. McClaren biographer Craig Bromberg documents how even this “business” arrangement subverted the traditional formalities of the day: "There were no commitments, no contracts or agreements, and McClaren didn't yet provide the boys with the cash or clothes he knew they would eventually need, but the more he looked at these kids... the more he realized they were 'his boys'."(1) His boys adopted the name of a New York street gang, thus The Sex Pistols, and with them Punk Rock, came to be.

In the months to follow the Sex Pistols would themselves become a precipitating factor of that “super new UK thing.” McClaren used his tenacity and marketing savvy to create a burgeoning new underground dominated by a do-it-yourself ethic of rugged creativity. Soon bands would emulate the Sex Pistols and buy or steal their own equipment, mimeograph their own “fanzines”, take to the road in “borrowed” milk trucks, and press their own records on cheap vinyl. A thriving cottage industry grew from behind the counters of places like SEX, for as Punks networked from shop to shop other owners eyed their patrons looking for their own bands to promote. Punk was slowly spreading throughout London when, in late 1976, the Sex Pistols laboriously started touring, playing various art schools and polytechnics in and around the London area. This touring produced an even larger fan base, and turned the slight buzz Punk produced into a steady hum.

In the months to follow the Sex Pistols would themselves become a precipitating factor of that “super new UK thing.” McClaren used his tenacity and marketing savvy to create a burgeoning new underground dominated by a do-it-yourself ethic of rugged creativity. Soon bands would emulate the Sex Pistols and buy or steal their own equipment, mimeograph their own “fanzines”, take to the road in “borrowed” milk trucks, and press their own records on cheap vinyl. A thriving cottage industry grew from behind the counters of places like SEX, for as Punks networked from shop to shop other owners eyed their patrons looking for their own bands to promote. Punk was slowly spreading throughout London when, in late 1976, the Sex Pistols laboriously started touring, playing various art schools and polytechnics in and around the London area. This touring produced an even larger fan base, and turned the slight buzz Punk produced into a steady hum.

The Sex Pistols performing in 1977. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

The Sex Pistols performing in 1977. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

The growing popularity of the Sex Pistols helped Punk transcend its localized beginnings and rooted it firmly at the heart of the growing social unrest felt by its followers. The Pistol’s concerts were violently energetic, and often resulted in fights and arrests. Lead singer Johnny Rotten taunted the crowd with statements like, “You don’t hate us as much as we hate you!” and begged them to “get pissed” and “destroy.”(2) As a result, raucous crowds often vandalized the concert halls, in some cases beyond repair. Members of the music press also started to notice Punk at this time. Particularly, Caroline Coon of The New Music Express began to follow the Pistol’s performances, and even though the reviews and articles she wrote were ultimately rejected or given limited space, they did have an impact on indoctrinating new adherents to Punk and gave the Pistols their first ally within the record industry. The fact that Punk gained very little mainstream recognition at this point served only to strengthen its core following, and allowed it to go on perfecting its trademark look and sound without the interference of A and R men. These elements would become key factors in Punk’s ultimate success, and would serve as effective tactics with which to spread the word, thus carrying Punk to the next level as a broader social movement.

As proper dress gave way to "wearing safety pins and ripped up T-shirts with insulting things on them", Punk followers would become more and more noticeable, thus allowing them to identify one another and present a visual appeal to would be members.(2) McClaren’s shop sold "striped shirts with slogans like 'Only Anarchists Are Pretty' and 'Modernity Kills Every Night'", and the Sex Pistols were his premiere models.(1) But this was more than fad and fashion. The Punk look created in SEX was a uniform that "became as self-consciously proletarian as it was aesthetic", and hinted at defining a Punk ideology.(4) It served as a symbol of the emerging group identity as well as a form of protest, and best of all it was relatively inexpensive. Everybody had old t-shirts lying around that they could dress up with a few strategically placed safety pins. Thus, in Punk performers working class youth saw people who looked like themselves via a fashion aesthetic that was easy to emulate, and that made a broad statement about how they felt.

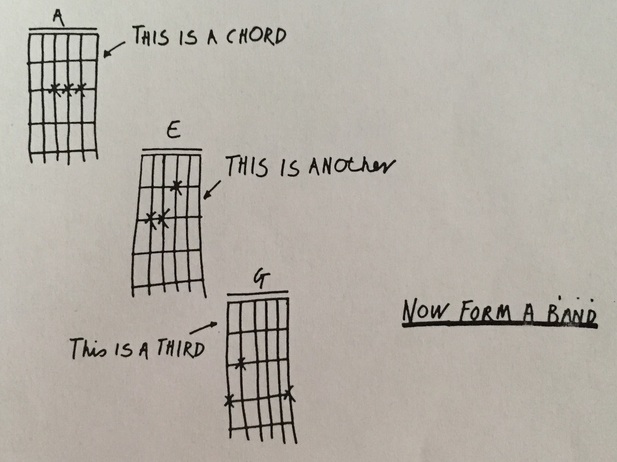

The utility and simplicity of Punk style was not just limited to fashion. It was also evident in the Punk sound, which was characterized by the "mastery" of a few, sloppy chords, minimal changes, and driving rhythm support, all cranked to the highest volume level. Tom Carson writes, “...they had defined the music in its purest terms: a return to basics which was deliberately primitive and revisionist.”(3) This sound redefined what was required of the musician in terms of skill. Clash lead vocalist, Joe Strummer, would comment on this while recounting his conversion to Punk, "...when I saw the Pistols I suddenly realized I wasn't alone in the fact that I couldn't play too well...I thought it was great cos' it just suddenly struck me that it didn't have to matter that much, you know?"(5) This facet of the Punk musical aesthetic was then proliferated to its audiences by many other new bands, which toured extensively in small neighborhood clubs, and began to produce their own records. The growth and ingenuity of these young bands helped to further spur on Punk’s grass roots popularity, and broadened its scope outside of Sex’s inner circle because the feeling was that, truly, anyone could easily join in, as illustrated by this cartoon from a fanzine dedicated to The Stranglers:

As proper dress gave way to "wearing safety pins and ripped up T-shirts with insulting things on them", Punk followers would become more and more noticeable, thus allowing them to identify one another and present a visual appeal to would be members.(2) McClaren’s shop sold "striped shirts with slogans like 'Only Anarchists Are Pretty' and 'Modernity Kills Every Night'", and the Sex Pistols were his premiere models.(1) But this was more than fad and fashion. The Punk look created in SEX was a uniform that "became as self-consciously proletarian as it was aesthetic", and hinted at defining a Punk ideology.(4) It served as a symbol of the emerging group identity as well as a form of protest, and best of all it was relatively inexpensive. Everybody had old t-shirts lying around that they could dress up with a few strategically placed safety pins. Thus, in Punk performers working class youth saw people who looked like themselves via a fashion aesthetic that was easy to emulate, and that made a broad statement about how they felt.

The utility and simplicity of Punk style was not just limited to fashion. It was also evident in the Punk sound, which was characterized by the "mastery" of a few, sloppy chords, minimal changes, and driving rhythm support, all cranked to the highest volume level. Tom Carson writes, “...they had defined the music in its purest terms: a return to basics which was deliberately primitive and revisionist.”(3) This sound redefined what was required of the musician in terms of skill. Clash lead vocalist, Joe Strummer, would comment on this while recounting his conversion to Punk, "...when I saw the Pistols I suddenly realized I wasn't alone in the fact that I couldn't play too well...I thought it was great cos' it just suddenly struck me that it didn't have to matter that much, you know?"(5) This facet of the Punk musical aesthetic was then proliferated to its audiences by many other new bands, which toured extensively in small neighborhood clubs, and began to produce their own records. The growth and ingenuity of these young bands helped to further spur on Punk’s grass roots popularity, and broadened its scope outside of Sex’s inner circle because the feeling was that, truly, anyone could easily join in, as illustrated by this cartoon from a fanzine dedicated to The Stranglers:

Punk would mobilize nationally as the simplicity of its sound opened doors for many would be musicians who were either too lazy or too intimidated to learn how to play. This served to set Punk bands apart from those who, in learning to play and play well, embodied the work ethic condoned by the rest of society (an ethic which in the eyes of many British teens was fruitless). Furthermore, Punk lyrics weren't sung so much as they were ranted, becoming, “a mixture of speech, recitative chanting or wordless cries or mutterings.”(3) The Punk vocal style was all English and all working class, and it distinguished Punks from other Brit artists whose accents suddenly disappeared in the midst of singing. This was intended to give the music a greater sense of force and power. Joe Strummer reflected on this when describing The Clash's first time in the studio with an established producer, "he said, 'Look, ... you better pronounce the words right.' So I made a big deal and really tried to pronounce it, but it just took all the piss out of it."(5)

Its message of angry individualism caused Punk to grow rapidly inward and outward. Bands sprung up from other Punk group's inner circles, such as Siouxsie and the Banshees, whose members could previously be seen standing with The Sex Pistols in publicity photos not as musicians, but as fans.(2) Still others shared the feelings of Strummer, becoming greatly affected by the impact of seeing the Pistols on stage. Virtually everywhere the Sex Pistols went they left a score of new Punk adherents in their wake. This is best exemplified by the growth of the Punk scene in Manchester and the birth of its core band, the Buzzcocks. Energized by seeing The Sex Pistols, Buzzcocks founder Pete Shelley grew from fan, to fanzine editor, to bandleader and record producer. The ease with which people moved in and out of Punk circles isn’t to imply that Punk had no identifiable leadership, but its leadership structure was never vividly defined, and very fluid. Each band was essentially a pseudo-social movement organization, having its own adherents that preferred that band over the others, but with all being equally accepted into the larger scheme of the Punk underground. The Punk look and sound would effectively erase any distinction between bands and their fans, with the act of performing simply being something that band members did as part of the ritual of Punk, serving a similar function to a choir at church. This would change as the movement progressed and achieved greater notoriety outside of its own circle. Groups like The Sex Pistols and The Clash would be labeled, either positively or negatively, as being responsible for Punk’s creation and growth to the exclusion of other forerunning groups, leading to petty jealousy and grandstanding. Its success also lead to a superstar mentality being conferred on core bands by the press, while loyal fans, much of whom were there from before the beginning, were left behind as Punk’s reputation grew larger.

Its message of angry individualism caused Punk to grow rapidly inward and outward. Bands sprung up from other Punk group's inner circles, such as Siouxsie and the Banshees, whose members could previously be seen standing with The Sex Pistols in publicity photos not as musicians, but as fans.(2) Still others shared the feelings of Strummer, becoming greatly affected by the impact of seeing the Pistols on stage. Virtually everywhere the Sex Pistols went they left a score of new Punk adherents in their wake. This is best exemplified by the growth of the Punk scene in Manchester and the birth of its core band, the Buzzcocks. Energized by seeing The Sex Pistols, Buzzcocks founder Pete Shelley grew from fan, to fanzine editor, to bandleader and record producer. The ease with which people moved in and out of Punk circles isn’t to imply that Punk had no identifiable leadership, but its leadership structure was never vividly defined, and very fluid. Each band was essentially a pseudo-social movement organization, having its own adherents that preferred that band over the others, but with all being equally accepted into the larger scheme of the Punk underground. The Punk look and sound would effectively erase any distinction between bands and their fans, with the act of performing simply being something that band members did as part of the ritual of Punk, serving a similar function to a choir at church. This would change as the movement progressed and achieved greater notoriety outside of its own circle. Groups like The Sex Pistols and The Clash would be labeled, either positively or negatively, as being responsible for Punk’s creation and growth to the exclusion of other forerunning groups, leading to petty jealousy and grandstanding. Its success also lead to a superstar mentality being conferred on core bands by the press, while loyal fans, much of whom were there from before the beginning, were left behind as Punk’s reputation grew larger.

Photo via Getty Images.

Photo via Getty Images.

This reputation would not go unchecked by the establishment for long. The anger and frustration expressed on stage, coupled with the violence off it, made many promoters reluctant to stage Punk shows for fear that their venues would be destroyed. Seeing bands like the Pistols live became increasingly hard to do, a fact that added to the energy and mystique of those shows that did occur. In addition, the Punk uniform was not something one could easily ignore when walking down the street, as Punks purposely sought to provoke by donning swastikas in addition to their multi-colored, outrageous hair cuts, nose rings and dog-collars. Their appearance either made Punks subject to fear or ridicule, often resulting in their being physically assaulted. Still, Punk was primarily an underground phenomenon until the evening of December 1, 1976. That was the night the Sex Pistols became a last minute fill-in guest on London’s Today show. Today host Bill Grundy personified everything that Punk did not want to be: old, middle class and conservative. The Pistols were at the least nonchalant, if not antagonistic about being on his show, and the tension that ensued during the interview culminated with Grundy losing his temper as Pistol Steve Jones called him, among other things, a sod, a bastard, a rotter, and a dirty fucker, all on live television. Clearly, the Pistol’s appearance on Today was one of the key events that gave rise to Punk’s notorious national prominence. Immediately after the show, studio telephones rang off the hook, while the morning papers vilified the Sex Pistols as spiked haired pied pipers, leading Britain’s youth astray, making them menaces to the cultural security of the realm.

There was indeed enough substance in Punk’s lyrics to support some of these fears. In 1890, Friedrich Engels wrote that, "political, legal, and philosophical theories... exercise their influence upon the course of the historical struggles and in many cases preponderate in determining their forms."(6) We’ve already seen how England’s socio-economic conditions created an angry new visual and musical aesthetic, but if Punk was to be seen as more than a fad, it would have to reflect an ideological view that differed greatly from its musical counterparts in its political and intellectual scope. Punk ideology was broad, varying by degree from band to band. But at its core was a searing indictment on blindly accepting the status quo. Punk wanted to open doors that couldn’t be opened merely by conforming to the accepted social norms. They became examples of sociologist Talcott Parson’s “innovators:” deviants who accepted the goals of individual success but rejected the usual means of achieving such success. That’s why learning to actually play your instruments became a sign of individual inadequacy, for true Punks weren’t supposed to play by the rules.

In his book, One Chord Wonders, Dave Laing documents how Punk successfully injected their mantra of rugged individualism and disregard for authority into its lyrics. By comparing the lyrical content of the debut albums of The Damned, The Clash, The Stranglers, The Sex Pistols and The Vibrators; "the first five Punk groups to achieve prominence in 1976-77," with the fifty top selling singles in Britain in 1976, Laing found that the Punk songs accurately reflected the discontent and frustration gripping the nation’s youth. Of the Punk songs sampled, 25% dealt with "social and political content" versus only 4% of the top fifty songs. The issues of songs from this category "included royalty, the USA, dead-end jobs, the police, watching television, record companies, sexual hypocrisy, war, anarchy, and riots." Still, another 25% of the Punk songs were concerned with "first person feelings," a topic keeping with the punk mantra of individuality, while only 3% of the top fifty songs touched on this area.(3) These figures reveal two major themes within Punk music that intertwined to form its dominant ideology: the disregard of established, traditional authority figures in favor of personal expression and self and class awareness. This sentiment was not unique to Punk and had, in fact gained notoriety within the 60s music scene. But unlike their politically conscious predecessors, the tone and delivery of the punk message was angrier. It not only struck out at the establishment, but also challenged its listeners to fight subservience to it. Thus, while the Beatles' hit "Revolution" affirmed that everything was going to be "all right", bands like the Sex Pistols saw that something was wrong and declared that there was "no future for you!" unless you made one for yourself.

Punks packaged these sentiments in a hard, leather-clad veneer that added to the power of their lyrics, and used their positions as artists to promote them to their fans. Sham 69 warned, "If the kids are united, then we'll never be divided." Bands like Stiff Little Fingers also "went straight for social relevance."(7) In their song, "Suspect Device," declaring "They play their games of power / they cut among the pack," while, "they deal us to the battle / but what do they put back?" In the chorus we are told, “Don’t believe them, don’t believe them! Don’t be bitten twice!” and to cast off the “suspect device” of materialism endorsed by the establishment. Others, like X-Ray Spex, challenged the artificiality of modern life with songs like "The Day the World Turned Day-Glo," while The Sex Pistols promoted ideas of "Anarchy in the UK" as just one of “the many ways to get what you want” (from “Anarchy in the UK”). Through the form and content of their music, Punk bands created an angry ideology of individual rebellion and nonconformity, and they encouraged their fans to grab onto it. It didn’t seek to overthrow the government or the established social order, but it recognized that the system as it stood was becoming less and less effective.

In his book, One Chord Wonders, Dave Laing documents how Punk successfully injected their mantra of rugged individualism and disregard for authority into its lyrics. By comparing the lyrical content of the debut albums of The Damned, The Clash, The Stranglers, The Sex Pistols and The Vibrators; "the first five Punk groups to achieve prominence in 1976-77," with the fifty top selling singles in Britain in 1976, Laing found that the Punk songs accurately reflected the discontent and frustration gripping the nation’s youth. Of the Punk songs sampled, 25% dealt with "social and political content" versus only 4% of the top fifty songs. The issues of songs from this category "included royalty, the USA, dead-end jobs, the police, watching television, record companies, sexual hypocrisy, war, anarchy, and riots." Still, another 25% of the Punk songs were concerned with "first person feelings," a topic keeping with the punk mantra of individuality, while only 3% of the top fifty songs touched on this area.(3) These figures reveal two major themes within Punk music that intertwined to form its dominant ideology: the disregard of established, traditional authority figures in favor of personal expression and self and class awareness. This sentiment was not unique to Punk and had, in fact gained notoriety within the 60s music scene. But unlike their politically conscious predecessors, the tone and delivery of the punk message was angrier. It not only struck out at the establishment, but also challenged its listeners to fight subservience to it. Thus, while the Beatles' hit "Revolution" affirmed that everything was going to be "all right", bands like the Sex Pistols saw that something was wrong and declared that there was "no future for you!" unless you made one for yourself.

Punks packaged these sentiments in a hard, leather-clad veneer that added to the power of their lyrics, and used their positions as artists to promote them to their fans. Sham 69 warned, "If the kids are united, then we'll never be divided." Bands like Stiff Little Fingers also "went straight for social relevance."(7) In their song, "Suspect Device," declaring "They play their games of power / they cut among the pack," while, "they deal us to the battle / but what do they put back?" In the chorus we are told, “Don’t believe them, don’t believe them! Don’t be bitten twice!” and to cast off the “suspect device” of materialism endorsed by the establishment. Others, like X-Ray Spex, challenged the artificiality of modern life with songs like "The Day the World Turned Day-Glo," while The Sex Pistols promoted ideas of "Anarchy in the UK" as just one of “the many ways to get what you want” (from “Anarchy in the UK”). Through the form and content of their music, Punk bands created an angry ideology of individual rebellion and nonconformity, and they encouraged their fans to grab onto it. It didn’t seek to overthrow the government or the established social order, but it recognized that the system as it stood was becoming less and less effective.

Perhaps nowhere was this ideology related back to the fan more effectively than in the music and actions of The Clash. "Damned for their integrity, attacked for injecting politics into their songs, (and) ridiculed for having ideals,"(8) The Clash were perhaps the most socially relevant, yet down to earth band of the Punk movement. Their song, "White Riot", captures these qualities well. Despite what the title suggests, this is not a song about white supremacy. In fact, it is a call for working class white youths to exhibit the same aggressiveness their black counterparts showed in 1975’s Notting Hill race riots. Members of The Clash witnessed these riots, and were struck by the resolve of the protesters in resisting their oppressors. Says Joe Strummer, "It was the one day of the year when the blacks were going to get their own back against the really atrocious way the police behaved."(2) Looking at the song that he wrote shortly thereafter, it seems he wanted to make sure that, if put into the same position, working class whites would follow the Notting Hill example:

|

|

White riot - I wanna riot

White riot - a riot of my own White riot - I wanna riot White riot - a riot of my own Black people gotta lot a problems But they don't mind throwing a brick White people go to school Where they teach you how to be thick An' everybody's doing Just what they're told to An' nobody wants To go to jail! White riot - I wanna riot White riot - a riot of my own White riot - I wanna riot White riot - a riot of my own |

All the power's in the hands

Of people rich enough to buy it While we walk the street Too chicken to even try it Everybody's doing Just what they're told to Nobody wants To go to jail! White riot - I wanna riot White riot - a riot of my own White riot - I wanna riot White riot - a riot of my own Are you taking over or are you taking orders? Are you going backwards Or are you going forwards? |

The song reveals the insight Strummer had in identifying the workings of the British class system, while revealing, at the same time, his anger towards it. The first verse serves two purposes. First, a possible solution for the problems of working class whites is offered in the form of violent protest. Second, a reference is made to an identifiable part of English culture that contributes to these problems: the educational system, "where they teach you how to be thick" and complacent. The second verse reveals why the schools are set up that way: to make sure the power stays with "the people rich enough to buy it," while the song ends with a direct, personal challenge to the listener to “go forwards” and change it. Songs like "White Riot," "Career Opportunities," and "1977" helped the band to establish themselves as "roots rock rebels", and created a link between themselves and their audience. They soon gained a reputation as a working man's group, a quality that would be reinforced by their stage presence. As one reviewer would note in The Melody Maker:

|

The Clash had just launched into their first encore... when the security, which the band had promised would be low key, spilled over into viciousness as a kid who was trying to get up on-stage was smashed. The group stopped playing immediately, horrified, and Mick Jones pulled the fan up on stage. Then... they let the kid chip in on vocals. And I don't mean they tolerated him – the dream-come-true-bloke probably sang more... than Joe Strummer... That's what Clash are all about, speaking for, with, and from working class youth, instead of talking down to them.(3)

|

The Clash also demanded that their records be sold below market value in order to make them more affordable. Such qualities endeared them to their fans, and helped the growth of all of Punk as a real movement for change. But despite its ideological grandstanding, Punk’s place in rock music was ultimately, and ironically, assured by the aggressiveness of those responsible for marketing it.

Underlying Punk’s social message, which as we’ve seen is directed squarely against the established social and economic structures, was the fact that it had unwittingly become a part of these structures. Without a doubt, Punk was seen as a money-making enterprise for people like McClaren. While all of the touring, fanzines, and bad publicity may have endeared the Sex Pistols to their fans and added to their outsider image, all of it was ultimately done to secure for them a conventional recording contract. As professional musicians, Punk bands had an obligation to produce and be profitable. This is the first and greatest irony of the Punk movement. Despite the style and content of their music or the outrageousness of their actions, Punk groups, beginning with the Sex Pistols, used the established means of the music machine to gain their greatest popularity. The marketplace was primed for something new, and that something would be the Punk product. Malcolm McClaren was a businessman, a de-facto member of the system the band he managed derided. Thus, from the beginning, Punk was chained to the boss, for the ideas McClaren was selling at SEX may’ve been radical; but, nevertheless, he was selling them. This dichotomy would become even more evident after Virgin Records signed the Pistols to a major recording contract. Other companies followed suit soon after, hoping to ride the Punk bandwagon to renewed financial success by quickly signing other Punk groups.

This blanket acceptance into the recording industry would lead Punk to a time when it struggled to stay true to its ethos while straddling the fence of commercial success. Nowhere was this dialectic more evident than in the marketing of the most notorious single ever to be released in England: the Sex Pistol’s, “God Save the Queen.” Because of its content and success, this song is a classic example of the dual nature of Punk as an indictment and affirmation of English authority. “God Save the Queen” was a burning tirade against the values of the British system as embodied in the person of Queen Elizabeth II:

Underlying Punk’s social message, which as we’ve seen is directed squarely against the established social and economic structures, was the fact that it had unwittingly become a part of these structures. Without a doubt, Punk was seen as a money-making enterprise for people like McClaren. While all of the touring, fanzines, and bad publicity may have endeared the Sex Pistols to their fans and added to their outsider image, all of it was ultimately done to secure for them a conventional recording contract. As professional musicians, Punk bands had an obligation to produce and be profitable. This is the first and greatest irony of the Punk movement. Despite the style and content of their music or the outrageousness of their actions, Punk groups, beginning with the Sex Pistols, used the established means of the music machine to gain their greatest popularity. The marketplace was primed for something new, and that something would be the Punk product. Malcolm McClaren was a businessman, a de-facto member of the system the band he managed derided. Thus, from the beginning, Punk was chained to the boss, for the ideas McClaren was selling at SEX may’ve been radical; but, nevertheless, he was selling them. This dichotomy would become even more evident after Virgin Records signed the Pistols to a major recording contract. Other companies followed suit soon after, hoping to ride the Punk bandwagon to renewed financial success by quickly signing other Punk groups.

This blanket acceptance into the recording industry would lead Punk to a time when it struggled to stay true to its ethos while straddling the fence of commercial success. Nowhere was this dialectic more evident than in the marketing of the most notorious single ever to be released in England: the Sex Pistol’s, “God Save the Queen.” Because of its content and success, this song is a classic example of the dual nature of Punk as an indictment and affirmation of English authority. “God Save the Queen” was a burning tirade against the values of the British system as embodied in the person of Queen Elizabeth II:

|

|

God save the queen

The fascist regime They made you a moron Potential H-bomb God save the queen She ain't no human being There is no future In England's dreaming Don't be told what you want Don't be told what you need There's no future, no future, No future for you God save the queen We mean it man We love our queen God saves God save the queen 'Cause tourists are money And our figurehead Is not what she seems Oh God save history God save your mad parade |

Oh Lord God have mercy

All crimes are paid When there's no future How can there be sin We're the flowers in the dustbin We're the poison in your human machine We're the future, your future God save the queen We mean it man We love our queen God saves God save the queen We mean it man And there is no future In England's dreaming No future, no future, No future for you No future, no future, No future for me No future, no future, No future for you No future, no future for you |

An original promo poster for the Sex Pistols' "God Save the Queen" single. Photo via Record Mecca.

An original promo poster for the Sex Pistols' "God Save the Queen" single. Photo via Record Mecca.

Obviously, the song’s tone is consistent with the Punk ideology of individualism and the questioning of authority, but there was more to it than that. Keeping with the adage that any publicity was good publicity, McClaren and Virgin Records chief, Richard Branson decided that “God Save the Queen” was to be released two weeks before the 25th Anniversary of the Queen’s coronation: The Silver Jubilee, and spared no expense in promoting it. “1,000 double-crown posters for use on London buses; 3,000 quad-sized posters for flyposting; 6,000 stickers; 3,000 streamers; transfers; T-shirts, as well as TV, radio and press advertisements” were produced with the intent of mass marketing the single and exploiting the Jubilee, and despite the fact that “the BBC refused to play it on the grounds of ‘gross bad taste’,”(2) it was named the single of the week by The Record Mirror, The Melody Maker, and The New Music Express. Attempts to censor “God Save the Queen” only fueled its popularity. As a result the song simultaneously supported one arm of the status quo while protesting another. The record industry had successfully exploited the anger and energy of Punk for profit as “God Save the Queen” went on to become the first British single to reach number one on the strength of record sales alone. So while “The Sex Pistols’ considerable, but ill-defined conviction lent moral authority to their attack on the status quo,”(2) it made little-known Virgin Records an established part of it. Furthermore, while one can also view the success of “God Save the Queen” as a confirmation of the Punk ideology and aesthetic by those who purchased it, it also validated Punk as part of the marketplace and, therefore, the “machine.” In short, it made rebellion fashionable, marketable, and profitable.

Punk was ironically being embraced by a large sector of the group it condemned, a fact that would play a great role in its overall failure to achieve real social change. Its mainstream acceptance would lead to tension among its core adherents, many of whom viewed the Punk foray into commercial music as a rejection of its morals in favor of profit. Its commercial success and its social relevance were both factors that lead to Punk’s ultimate disintegration via a process Sociologist David Riesman calls “restriction by partial incorporation.”(3) Partial incorporation occurs when “...the popular mainstream... renews itself by drawing in elements from musical genres which had previously remained separate.”(3) For punk, this included not only commercial but also critical and peer acceptance. Mainstream musicians such as the Who’s, Pete Townsend, heralded Punk for being “totally real.” Also, Sex Pistols lead singer Johnny Rotten (now John Lydon), in his memoir, Rotten, recounted his dismay at being chased by Paul McCartney, who wished to have Rotten perform on his next album.(9) The irony in this is that both Townsend and McCartney were members of groups who, much like The Sex Pistols, had questioned the prevailing thought of their day and were both, via the same process of partial incorporation, co-opted into the mainstream of society and then considered “sell-outs.”

Punk was ironically being embraced by a large sector of the group it condemned, a fact that would play a great role in its overall failure to achieve real social change. Its mainstream acceptance would lead to tension among its core adherents, many of whom viewed the Punk foray into commercial music as a rejection of its morals in favor of profit. Its commercial success and its social relevance were both factors that lead to Punk’s ultimate disintegration via a process Sociologist David Riesman calls “restriction by partial incorporation.”(3) Partial incorporation occurs when “...the popular mainstream... renews itself by drawing in elements from musical genres which had previously remained separate.”(3) For punk, this included not only commercial but also critical and peer acceptance. Mainstream musicians such as the Who’s, Pete Townsend, heralded Punk for being “totally real.” Also, Sex Pistols lead singer Johnny Rotten (now John Lydon), in his memoir, Rotten, recounted his dismay at being chased by Paul McCartney, who wished to have Rotten perform on his next album.(9) The irony in this is that both Townsend and McCartney were members of groups who, much like The Sex Pistols, had questioned the prevailing thought of their day and were both, via the same process of partial incorporation, co-opted into the mainstream of society and then considered “sell-outs.”

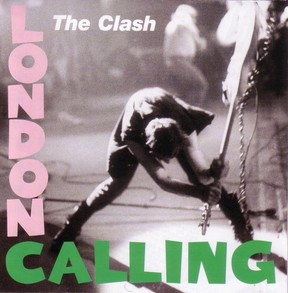

The cover to The Clash's iconic 1979 release.

The cover to The Clash's iconic 1979 release.

Punk’s success among the critics also helped its demise by speeding its transition into the mainstream, thus reflecting Riesman’s process of partial incorporation. Greil Marcus, in writing a review of the 1979 Clash double album, London Calling, claimed that the band had “found a place” for itself in all of rock history,(10) while Rolling Stone Magazine would hail that same album as the most important album of the 80s (it wasn’t released in the US until early 1980). Not to be outdone, The New Trouser Press Record Guide gushed that The Sex Pistol’s contribution, not just to rock music, but all to popular culture “can hardly be overstated,”(8) while record executive Derek Green ironically put them into the same class as The Who and The Rolling Stones: “They give me much the same feelings.”(3) Such accolades had a profound effect on the punk movement and its fans, many of whom accused the more successful bands of selling out. But what had happened was beyond the control of the artists, and had an even greater impact on them. In 1978 The Sex Pistols disintegrated after a tour of the US. Rotten left the group immediately after their fabled concert at San Francisco’s Winterland Ballroom, and soon sued McClaren for breach of contract. Later that year, bass player Sid Vicious was found dead of a drug overdose in New York while awaiting trial on charges of second degree murder in the death of his girlfriend, Nancy Spungeon. Other lesser bands, like The Rezillos, 999, and Subway Sect would soon follow the Pistols’ lead, disbanding into musical obscurity while others like The Jam, The Buzzcocks, The Police, and Billy Idol, formerly of Generation X, tried exploring new musical territories. They then rode this “new wave” into the eighties, where The Police, Idol, and a band of former Jam members, The Style Council, would find even greater success. In short, Punk artists were seemingly forced to choose between abandoning the shrill resolve of the music it had created or losing the fruits of mainstream acceptance. Again, The Clash are a prime example of this stage of punk development.

At first, The Clash survived the supposed demise of Punk that was embodied in the collapse of The Sex Pistols; and, despite modifying their sound somewhat, kept the anger of their social themes intact – even broadened them, taking on global issues. After learning proper chord changes, they continued to produce songs with themes ranging from the alienation of capitalist society (“Clampdown,” “Lost in the Supermarket”), to the plight of Amer-Asians orphans in Vietnam (“Straight to Hell”), or the United State’s interference in South American politics (“Washington Bullets”). But, after reaching the pinnacle of commercial success by having a top ten album and single on the American charts with Combat Rock and “Rock the Casbah” (a song about the Ayatollah’s banning of rock music in Iran), respectively The Clash imploded. Shocked by the band’s great success, Joe Strummer disappeared to Paris, only to return months later and disband the group. It seemed that “despite the Punk attempt to destroy the pop system, a pop star was all (guitarist and co-leader) Mick Jones had ever wanted to be.”(10) Strummer grew deeply depressed over the inherent contradictions The Clash embodied. He later attempted to reform the band with new members and a return “back to the roots” of Punk, while Jones formed the dance-pop band, Big Audio Dynamite. After releasing one album, This Is the Clash, which failed to garner any significant critical or commercial attention, Strummer and the new Clash faded from the public eye, while Jones scored renewed success with B.A.D. Strummer’s new Clash would resurface shortly again in May, 1985, outside of a concert by a new “post-punk” band The Alarm, playing for change and looking for a place to stay. Strummer was true to his word. He had indeed returned to his roots, and in turn cemented his status as a Punk icon, the ultimate irony for a man who saw Punk as a means to “destroy all heroes.”(10)

At first, The Clash survived the supposed demise of Punk that was embodied in the collapse of The Sex Pistols; and, despite modifying their sound somewhat, kept the anger of their social themes intact – even broadened them, taking on global issues. After learning proper chord changes, they continued to produce songs with themes ranging from the alienation of capitalist society (“Clampdown,” “Lost in the Supermarket”), to the plight of Amer-Asians orphans in Vietnam (“Straight to Hell”), or the United State’s interference in South American politics (“Washington Bullets”). But, after reaching the pinnacle of commercial success by having a top ten album and single on the American charts with Combat Rock and “Rock the Casbah” (a song about the Ayatollah’s banning of rock music in Iran), respectively The Clash imploded. Shocked by the band’s great success, Joe Strummer disappeared to Paris, only to return months later and disband the group. It seemed that “despite the Punk attempt to destroy the pop system, a pop star was all (guitarist and co-leader) Mick Jones had ever wanted to be.”(10) Strummer grew deeply depressed over the inherent contradictions The Clash embodied. He later attempted to reform the band with new members and a return “back to the roots” of Punk, while Jones formed the dance-pop band, Big Audio Dynamite. After releasing one album, This Is the Clash, which failed to garner any significant critical or commercial attention, Strummer and the new Clash faded from the public eye, while Jones scored renewed success with B.A.D. Strummer’s new Clash would resurface shortly again in May, 1985, outside of a concert by a new “post-punk” band The Alarm, playing for change and looking for a place to stay. Strummer was true to his word. He had indeed returned to his roots, and in turn cemented his status as a Punk icon, the ultimate irony for a man who saw Punk as a means to “destroy all heroes.”(10)

|

What’s left of Punk today differs little socially from what remains of the 60s music scene. Punk is so viable a commercial genre that a separate sales chart category, catchingly dubbed “alternative” has been created by the recording industry to document its success, while Hip Hop and Rap became the next genres to embrace and sell rebellion. Even more ironic (or tragic, depending on your view), was the 1996 reunion of the Sex Pistols, with original bassist Glenn Matlock taking the place of Sid Vicious. The newly united Pistols toured under the banner, “We’re Fat, Forty, and Back,” with lead singer Lydon proclaiming that, “this time it’s for the money!” and deriding those tragic elements of Punk’s past as a result of self abuse and delusions of grandeur.(11) The Pistols toured again in 2003, with Rotten proudly proclaiming that the band would never record new material, stating "We only needed to make one album to define how the world is."(12) Like the Beatles and the Rolling Stones before them, both the Sex Pistols and the Clash have been enshrined in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame (though the Pistols refused to attend).

|

|

In the end one cannot escape the fact that for all its anger, Punk could not lower the unemployment rate, or stop the rise of Thatcherism, or even survive its fame intact. Most of its fans matured and entered the mainstream along with their more notable counterparts. Yet despite its failure to promote long lasting social change for the whole of society, one must not deny the profound effect punk had on the course of popular music, or its ability to inspire individuals to act. Punks and their artistic progeny worked to end Apartheid, stop nuclear proliferation, ease hunger, and it spoke up for the environment to the fore. It drew media attention to organizations like Amnesty International and Greenpeace (to name just a few). Artists as diverse as U2, Nirvana, and Public Enemy all cite it as an influence on their artistic development, and while the Punk sound and style is decidedly mainstream now, so are many of the causes artists championed. That's a good thing.

- Bromberg, Craig. The Wicked Ways of Malcolm McClaren.

- Savage, Jon. England’s Dreaming: Anarchy, Sex Pistols, Punk Rock and Beyond.

- Laing, Dave. One Chord Wonders: Power and Meaning in Punk Rock.

- O’Hara, Craig. The Philosophy of Punk: More Than Noise.

- Interview (No interviewer given). The Story of The Clash, Vol. I.

- Eagleton, Terry. Marxism and Literary Criticism.

- Savage, Jon. Liner note from DIY: The Modern World: UK Punk Vol. II.

- Robbins (Ed.), Ira A. The New Trouser Press Record Guide.

- Lydon, John (with Keith and Kent Zimmerman). Rotten: No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs.

- Marcus, Greil. Ranters and Crowd Pleasers: Punk in Pop Music, 1977-92.

- Schoener, Karen. “God Save the Queen, God Save us All.” Newsweek, June 24,1996.

- "Sex Pistols On Rock Hall Induction: 'We're Not Coming'." Billboard, February 24, 2006.

Header art by T. Guzzio. Original photo by B. Mazzer.

CONNECT WITH TOM:

In addition to editing Prodigal's Chair, Tom is a teacher, father, husband, writer, artist, futbol fan and slightly maladjusted optimist. Tom lives in Beverly, Massachusetts with his wife and their aging (yet still ticking) cocker spaniel, Honey (who approves this message). You can connect with him on Twitter @t_guzzio, or via email at [email protected].

ADD YOUR VOICE:

ABOUT COMMENTS:

At Prodigal's Chair, thoughtful, honest interaction with our readers is important to our site's success. That's why we use Disqus as our comment / moderation system. Yes, you will need to login to leave a comment - with either your existing Facebook, Twitter, or Google+ account - or you can create your own free Disqus account. We do this for a couple of reasons: 1) to discourage trolling, and 2) to discourage spamming. Please note that Disqus will never post anything to your social network accounts unless you authorize it to do so. Finally, if you prefer you can always email comments directly to us by clicking here.