Viewing the Grand Canyon from the South Rim provides an iconic view, but no sign of the waterfalls and greenery hidden within. Photo: C. Mattera.

Viewing the Grand Canyon from the South Rim provides an iconic view, but no sign of the waterfalls and greenery hidden within. Photo: C. Mattera.

The Grand Canyon is a landscape of great diversity. Viewing the famous gorge from one of its rims, as most visitors experience the Canyon, it’s impossible to imagine the variety contained within its walls. From the lofty bird’s eye perch at any one of the many scenic vistas scattered throughout the national park one is greeted by a seemingly endless wonderland of red rock – mesas, buttes, spires and cliffs – all sunburnt and exposed to the eons, yet shrouded in the mystery of the desert. It’s been said the average visitor to the Grand Canyon spends about five hours in the park, and only about 17 minutes viewing the Canyon itself.

Many come away satisfied; they have seen the iconic landscape, are able to tick it off their tour itinerary or bucket list, and move onto other sights. But there are those for whom the 17 minutes is only the beginning. With curiosity piqued, these souls want to know the Grand Canyon on some other level. Really know it – in a way that a 17-minute viewing could never allow. The spell the Canyon casts on these folks can be obsessive, and it can last a lifetime. I know this to be true firsthand, for I have been a hopeless Grand Canyon addict since 1990 when I took my very first look at the Big Ditch from Mather Point, followed quickly by a hike down the South Kaibab Trail to Cedar Ridge. It was only a few hours in duration and then my travel partner and I were off in the car to another destination, but the experience set in motion the gears in my mind anxiously scheming and planning a way to get back to Grand Canyon, and to truly know it from the inside out.

From that point forward I returned to the Grand Canyon several times annually for many years. With various small teams, and often solo, I hiked every trail into the Canyon from the South Rim, and most of the trails into the Canyon from the North Rim. Then I ventured further, off trail and off route, using a map and compass to navigate travel lasting from one to three weeks in the backcountry. Sometimes a rope was necessary for lowering packs, sometimes for a hand line and occasionally to rig a rappel. Pushing deeper into the side canyons, grottos, and hidden springs, my business became the business of uncovering the secrets of Grand Canyon.

Many come away satisfied; they have seen the iconic landscape, are able to tick it off their tour itinerary or bucket list, and move onto other sights. But there are those for whom the 17 minutes is only the beginning. With curiosity piqued, these souls want to know the Grand Canyon on some other level. Really know it – in a way that a 17-minute viewing could never allow. The spell the Canyon casts on these folks can be obsessive, and it can last a lifetime. I know this to be true firsthand, for I have been a hopeless Grand Canyon addict since 1990 when I took my very first look at the Big Ditch from Mather Point, followed quickly by a hike down the South Kaibab Trail to Cedar Ridge. It was only a few hours in duration and then my travel partner and I were off in the car to another destination, but the experience set in motion the gears in my mind anxiously scheming and planning a way to get back to Grand Canyon, and to truly know it from the inside out.

From that point forward I returned to the Grand Canyon several times annually for many years. With various small teams, and often solo, I hiked every trail into the Canyon from the South Rim, and most of the trails into the Canyon from the North Rim. Then I ventured further, off trail and off route, using a map and compass to navigate travel lasting from one to three weeks in the backcountry. Sometimes a rope was necessary for lowering packs, sometimes for a hand line and occasionally to rig a rappel. Pushing deeper into the side canyons, grottos, and hidden springs, my business became the business of uncovering the secrets of Grand Canyon.

|

Packs weighed up to 50 pounds, and included camping and canyon gear, 600 feet of rope, wetsuits, food for three days, and a lot of ambition. Photo: A. Turchon.

|

In 2011 I contacted Todd Martin, a publisher of an online hiking guide to the Southwest. He had a lot of Grand Canyon route information on his site, much of which I had already hiked, and I figured he’d be a good resource about Phantom Creek Canyon, a side canyon in The Grand that I was interested in descending. Todd did provide the information I was looking for, and also noted he had a new guide book to technical canyoneering in Grand Canyon, called Grand Canyoneering: Exploring the Rugged Gorges and Secret Slots of the Grand Canyon, which would be out in the summer of 2011.

I was ecstatic about this forthcoming guidebook. I had been technical canyoneering for years to that point (technical meaning the use of ropes and rock climbing gear to descend canyons), but most of the well known technical canyons were up in Utah, and little to no information was available to technical canyoneers about Grand Canyon. With the publication of Todd’s book, over one hundred technical side canyon adventures became available to those with the skills, stamina and desire. Once available to the public, I wasted no time and secured the book immediately, reading all 400 pages cover to cover in about two days. |

Garden Creek Canyon is one of the most magnificent places on earth from which I am happy to have escaped. It’s a narrow defile, a short side canyon responsible for draining winter run off, summer monsoons, and the creek’s own springs which flank the headwall at the start of the side canyon. Lush describes the vegetation along the watercourse, and the chutes and pour-offs are scoured smooth by the millennial flow of water. Contained within the hidden, technical, half-mile canyon are a handful of waterfalls, the shortest of which is 120 feet, and the longest dropping over 400 feet. Along with a number of other obstacles, these falls would have to be dealt with appropriately in order to complete a descent of Garden Creek Canyon. On May 11, 2012 as part of a team of three, I set out with just that goal.

Steve Stellato, Andrew Turchon, and I packed our gear together by the side of the road in Grand Canyon National Park at about mid day, and shouldering loads upwards of 50 pounds we began the five mile hike into the Canyon to an area known as Indian Garden, a prime camping spot along upper Garden Creek. Steep, but direct, there were no route finding issues, and soon enough we were camped several thousand feet below the South Rim, listening to the honking of canyon tree frogs in the rushes along the creek. With gear sorted, and the following day’s itinerary laid out clearly, we slept under a universe of stars, anxious and excited to descend Garden Creek Canyon the following day, a route which to that point had only been dropped by a small number of parties before ours. This was still the frontier, and we were both nerved up and pumped up to have the opportunity to descend.

Steve Stellato, Andrew Turchon, and I packed our gear together by the side of the road in Grand Canyon National Park at about mid day, and shouldering loads upwards of 50 pounds we began the five mile hike into the Canyon to an area known as Indian Garden, a prime camping spot along upper Garden Creek. Steep, but direct, there were no route finding issues, and soon enough we were camped several thousand feet below the South Rim, listening to the honking of canyon tree frogs in the rushes along the creek. With gear sorted, and the following day’s itinerary laid out clearly, we slept under a universe of stars, anxious and excited to descend Garden Creek Canyon the following day, a route which to that point had only been dropped by a small number of parties before ours. This was still the frontier, and we were both nerved up and pumped up to have the opportunity to descend.

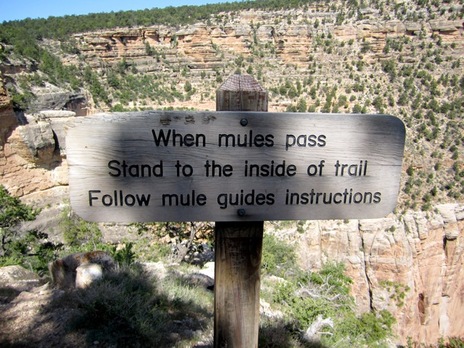

Mules and hikers share the way on the Bright Angel Trail. Photo: A. Turchon.

Mules and hikers share the way on the Bright Angel Trail. Photo: A. Turchon.

The next morning, after a hot breakfast and coffee in camp, we were on the move. Two miles further down, the Bright Angel Trail – which followed Garden Creek – made a wide bend away from the creek itself, and we knew this was the place where we would leave the trail behind. This was the start of the technical section of Garden Creek Canyon, and we immediately made our way off the trail and into the watercourse of the creek. Faced at once with a few down climbs, we choose to rope up for safety and descended the steep chutes over a series of short rappels. Soon we were at the top of the first real rappel, a waterfall of 120 feet. At this place Garden Creek made its point known to us, it asserted itself, and was undeniably a spot of exceptional beauty coupled with the drama associated with an impending swift water rappel. We located an anchor point, set ropes, and descended the falls without trouble. The force of the water was strong, and while on rappel it pushed, swept and pawed at each rappeller. Concentration, attention to foot placement on the slippery vertical rock, and rappelling skill were all necessary for a safe descent. We learned at this point what we should have known going in – that double strand rappelling (using two strands of the rope to lower one’s self) was a bad idea in swift moving water. The lines easily tangled, and rope management became an issue. Having completed the first rappel, over the 120 foot falls, we had come away with an important lesson, and all subsequent rappels over falls were performed single strand with the pull cord end of the rope tossed down last, or carried down in a backpack and fed out while rappelling the swift water drops.

At this point, due to the time it took to sequence our party members down the drop, coupled with the rope management issue we were working out, several hours since we left camp had passed. We were not worried about anything at this point, and the time we had “wasted” would – we felt – come back to us now that we were employing better techniques for the swift water rappels.

At this point, due to the time it took to sequence our party members down the drop, coupled with the rope management issue we were working out, several hours since we left camp had passed. We were not worried about anything at this point, and the time we had “wasted” would – we felt – come back to us now that we were employing better techniques for the swift water rappels.

Steve Stellato on the 120 foot waterfall rappel. Photo: C. Mattera.

Steve Stellato on the 120 foot waterfall rappel. Photo: C. Mattera.

Immediately after completing the 120 foot waterfall rappel, we were deposited at the brink of the 400 foot waterfall. We planned on rappelling this drop in two stages. The first 200 foot rope was set, on a carabineer block, for the first stage of the falls. We knew that half way down the falls there was located a single rock climber’s bolt just above a small ledge which should fit two or three people. Our plan was for each party member to descend to the “bolt station,” rope to be retrieved, and the second stage of the rappel to be set and then descended to the bottom of the large waterfall. It was during this process when fear and loathing overtook us. Our first descentionist, Andrew, rigged into the rope. Having only one operational walkie-talkie (the other accidentally took a swim in a pool) we worked through a few hand signals as a means to communicate over the roar of the flowing water. With that done, and after posing for some photographs at the brink of the large falls, Andrew began his rappel with no fanfare. Working his way over the lip of the falls, and following the flow of the water, we were astounded how deep into the Canyon we were. From the top of the falls, we could easily see the nearly 2-billion year old Vishnu Schist, black as coal, and the reddish intrusions of the Zoroaster Granite. Following my buddy with my eyes amid a backdrop of magnificent, ancient rock, all seemed wonderful in the world. As time passed I presumed I would receive a signal from Andrew that he was at the bolt station, anchored into the bolt, had taken himself off rope, and was ready for the next canyoneer to descend. My heart raced when I saw my partner standing on an outcropping of rock left of the watercourse, and frantically waving his hands. Andrew, unable to locate the needed bolt which we would find out days later was hidden under a “rooster tail” – a wave of rushing water – unseen and desperately needed, was now safe on the rock outcropping. The walkie-talkies would have come in handy at that point, and not having them spawned a series of hand gestures and arm flailing designed to communicate over the 200 vertical feet of rushing water. Screaming to each other was futile as the roar of the water flow was far too loud.

A lot went through my mind as I stood at the brink of the 400-foot falls. I remembered my twenty-year history of safety, and of getting all my partners out of any jams. But I also knew that, truth be told, those jams numbered to zero, really – just minor issues and one unplanned bivouac. This was uncharted territory. The place surrounding our party was absolutely astounding in its beauty and wild nature but this was lost on us at that time. A decision needed to be made. Andrew was unable to ascend from his safe perch on the ledge. He was in no immediate danger; however, he was unable to ascend to the top of the falls and unable to lower down to the bottom. For all intents and purposes, he was stuck.

What to do, what to do? I could have rappelled down towards Andrew looking for the single bolt station on the wall. Had I found it, I would have been able to bring Andrew up to it, and then Steve down to it, wherein we all could have retrieved our ropes and then rappelled the remaining 200 feet of the big falls to the canyon floor. But if I didn’t find that single bolt, I would have been in the same predicament as my partner: stranded on the rock outcropping. At that point, Steve above us would have been unable to assist us in any manner. Ultimately, that may have led to our spending an unintended night or more stranded in Garden Creek Canyon, and likely a search and rescue operation which would have been risky, expensive, and unnecessary. So rather than gamble on finding the bolt, I took the conservative and safe course of action. I signaled to Andrew to disconnect from the rope. He was in a safe place; I could see that from above. Once disconnected, I pulled the two hundred foot rope up to the brink of the falls, tied it together to another two hundred foot rope, and tossed the whole four hundred feet down the falls. This newly fastened 400-footer would allow everyone to rappel safely to the bottom of the four hundred foot falls, but it would be impossible to retrieve. While assuring safety to all members of the party, our actions would result in the loss of four hundred feet of premium line. Also, leaving the rope behind would be leaving a trace, and our backcountry travels are always based on the leave no trace ethic. At the bottom of the big falls all members of the party were adrenalized. We had seen ourselves through a situation which could have gone terribly wrong, were now staring up the big falls in marvel, yet our fellowship still had one more large obstacle, and as we would find out soon, many more smaller obstacles. We were feeling good, but were hardly out of the woods, so to speak.

A lot went through my mind as I stood at the brink of the 400-foot falls. I remembered my twenty-year history of safety, and of getting all my partners out of any jams. But I also knew that, truth be told, those jams numbered to zero, really – just minor issues and one unplanned bivouac. This was uncharted territory. The place surrounding our party was absolutely astounding in its beauty and wild nature but this was lost on us at that time. A decision needed to be made. Andrew was unable to ascend from his safe perch on the ledge. He was in no immediate danger; however, he was unable to ascend to the top of the falls and unable to lower down to the bottom. For all intents and purposes, he was stuck.

What to do, what to do? I could have rappelled down towards Andrew looking for the single bolt station on the wall. Had I found it, I would have been able to bring Andrew up to it, and then Steve down to it, wherein we all could have retrieved our ropes and then rappelled the remaining 200 feet of the big falls to the canyon floor. But if I didn’t find that single bolt, I would have been in the same predicament as my partner: stranded on the rock outcropping. At that point, Steve above us would have been unable to assist us in any manner. Ultimately, that may have led to our spending an unintended night or more stranded in Garden Creek Canyon, and likely a search and rescue operation which would have been risky, expensive, and unnecessary. So rather than gamble on finding the bolt, I took the conservative and safe course of action. I signaled to Andrew to disconnect from the rope. He was in a safe place; I could see that from above. Once disconnected, I pulled the two hundred foot rope up to the brink of the falls, tied it together to another two hundred foot rope, and tossed the whole four hundred feet down the falls. This newly fastened 400-footer would allow everyone to rappel safely to the bottom of the four hundred foot falls, but it would be impossible to retrieve. While assuring safety to all members of the party, our actions would result in the loss of four hundred feet of premium line. Also, leaving the rope behind would be leaving a trace, and our backcountry travels are always based on the leave no trace ethic. At the bottom of the big falls all members of the party were adrenalized. We had seen ourselves through a situation which could have gone terribly wrong, were now staring up the big falls in marvel, yet our fellowship still had one more large obstacle, and as we would find out soon, many more smaller obstacles. We were feeling good, but were hardly out of the woods, so to speak.

After a short time at the bottom of the big falls relishing the freedom of being unfettered from the four hundred foot rappel, we hurried along. It was not long before the last major falls, a 150-footer, blocked our passage down canyon. We had one rope remaining, a two hundred foot line. It would be enough to rappel the drop, but this rope too would not be retrievable. In order to retrieve the rope we would have needed more line, 100 feet more line. But all our other rope was still hanging behind us at the big falls. Leaving the rope behind was inevitable, so we rigged it for the rappel and enjoyed what may have been the sweetest waterfall rappel in Garden Creek Canyon. The water was funneled into a vertical joint or crack in the rock, and flanked on both sides by mosses and ferns contrasting wonderfully against the red hue of the Zoroaster Granite. Completing the rappel, and standing in the flow of the clear Garden Creek waters, our party was elated and exhausted. We had completed our objective, or so we thought, and believed the Bright Angel Trail was right around the corner. We were anxious to locate the trail and hike the steep two miles up a section known as the Devil’s Corkscrew back to our basecamp. However, with no rope remaining and minimal nylon webbing left in our gear supply, we encountered a series of additional down climbs into pools and down drop-offs. In a number of cases we would have felt more comfortable rappelling, given our exhaustion and the nature of the terrain. Being out of material, however, we made due as best we could with whatever we had remaining, building hand lines from small segments of webbing tied together. One last down climb, over and past a garden of cacti and cat’s claw was a little hairy for our already frazzled nerves, but it led to the Bright Angel Trail, and our escape from Garden Creek Canyon.

Post Hike: Andrew Turchon and Christopher Mattera. Photo: C. Mattera.

Post Hike: Andrew Turchon and Christopher Mattera. Photo: C. Mattera.

A couple of hours later, sitting in the relative safety of camp, as dusk was descending on the canyon, and under the first stars of the evening, I sat shivering, unable to get warm. Emotional exhaustion, physical fatigue, dehydration and the heat on the climb out the Devil’s Corkscrew had taken its toll. A canyon which we had planned to spend 3 or 4 hours descending turned into a ten hour plus day. Decisions were made, obstacles overcome, and all were in one piece under the Cottonwood trees at Indian Garden, our basecamp. Rather than the glow of achievement associated with completing an objective such as Garden Creek Canyon, the experience felt anticlimactic. Passing through a canyon, or any wild place for that matter, and leaving no trace of your passage is a beautiful, almost spiritual, experience for many people. Such is certainly true for our small fellowship. But leaving six hundred feet of rope, and a hundred feet of webbing fixed in place in the canyon was anathema to leaving no trace. Overtime, flash floods would certainly wash out the canyon, including our ropes, and nature would have restored itself as nature always does. That was not the point. The following day we hiked the five miles up and out of Grand Canyon with more than just our heavy packs weighing us down. We had completed Garden Creek Canyon, true, but we did not do so in high style.

Days after returning to the East Coast we contacted Todd Martin, and recounted our descent of Garden Creek Canyon. He told us the number one priority at that time was getting the party down safely, and that was accomplished. “Now,” he said, “you know what you have to do.” We had to get back in there and remove those ropes and webbing. Our mess needed to be cleaned. But we were nearly 3,000 miles away and would not be able to return to the Canyon for several weeks, likely longer. Todd Martin, along with Coalition for American Canyoneers (CAC) member Rich Rudow, formed a small group and went through Garden Creek Canyon the following week as part of a service project and cleaned out our gear. With them they took a backcountry ranger from the National Park Service, providing her with the opportunity to view Garden Creek first hand and to discuss canyoneering in the park. Our ropes were left to dry in the horse stables at the South Rim of Grand Canyon for a week and then shipped back to us back East.

Every experience provides opportunities for success and failure. There are always forks in the road of life. Making the best decision possible at any one time, under any given set of circumstances, then living with it and moving forward, is often the best we can hope for in many instances. Garden Creek Canyon in Grand Canyon is one of those very special places where seldom a foot is trod. The canyon gave us many opportunities to practice decision making and plenty of obstacles through which we had to work. Ultimately everyone who entered the canyon also exited the canyon, and under their own power. Several years later, looking back on the experience, despite our grand conundrum, I am happy to have spent time in Garden Creek Canyon, and think back on that special place with reverence.

Days after returning to the East Coast we contacted Todd Martin, and recounted our descent of Garden Creek Canyon. He told us the number one priority at that time was getting the party down safely, and that was accomplished. “Now,” he said, “you know what you have to do.” We had to get back in there and remove those ropes and webbing. Our mess needed to be cleaned. But we were nearly 3,000 miles away and would not be able to return to the Canyon for several weeks, likely longer. Todd Martin, along with Coalition for American Canyoneers (CAC) member Rich Rudow, formed a small group and went through Garden Creek Canyon the following week as part of a service project and cleaned out our gear. With them they took a backcountry ranger from the National Park Service, providing her with the opportunity to view Garden Creek first hand and to discuss canyoneering in the park. Our ropes were left to dry in the horse stables at the South Rim of Grand Canyon for a week and then shipped back to us back East.

Every experience provides opportunities for success and failure. There are always forks in the road of life. Making the best decision possible at any one time, under any given set of circumstances, then living with it and moving forward, is often the best we can hope for in many instances. Garden Creek Canyon in Grand Canyon is one of those very special places where seldom a foot is trod. The canyon gave us many opportunities to practice decision making and plenty of obstacles through which we had to work. Ultimately everyone who entered the canyon also exited the canyon, and under their own power. Several years later, looking back on the experience, despite our grand conundrum, I am happy to have spent time in Garden Creek Canyon, and think back on that special place with reverence.

Header image by T. Guzzio. Original photo by the author.

CONNECT WITH CHRISTOPHER:

Christopher Mattera has been descending and photographing technical canyons on the Colorado Plateau for twenty-five years. His photography appears in Moab Canyoneering: Exploring Technical Canyons Around Moab, the newest guide book to technical canyoneering on the Colorado Plateau, recently published by Sharp End Publications. Contact Christopher Mattera, Ed.D. at [email protected].

ADD YOUR VOICE:

ABOUT COMMENTS:

At Prodigal's Chair, thoughtful, honest interaction with our readers is important to our site's success. That's why we use Disqus as our comment / moderation system. Yes, you will need to login to leave a comment - with either your existing Facebook, Twitter, or Google+ account - or you can create your own free Disqus account. We do this for a couple of reasons: 1) to discourage trolling, and 2) to discourage spamming. Please note that Disqus will never post anything to your social network accounts unless you authorize it to do so. Finally, if you prefer you can always email comments directly to us by clicking here.