Photography is, for me, a spontaneous impulse coming from an ever-attentive eye, which captures the moment and its eternity. - Henri Cartier-Bresson

When I was seventeen I attended a 2-year photography program in Boston, taking hundreds of pictures between 1987 and 1989. I first walked through the school’s doors as a rather shy girl, and a novice photographer with no previous training at all. The program encouraged students to experiment in all types of photography before settling on a major: Portraiture/Wedding, Advertising/Commercial, Journalism, Black and White Studies or Color Studies. I worked in all these areas before finding my own style of editorial portraiture and street photography, inspired by Annie Leibovitz, Harry Benson, Mary Ellen Mark, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Helen Levitt, Eugène Atget and many others. I realized early on that my photography would always include people—endlessly fascinating, ever changing, and with limitless resources; as far as I was concerned, people would always be in my best images. Some of my fellow students preferred photographing in the studio, setting up still life scenes, adjusting lights, working in solitary; for me, my camera helped me overcome my timidity, and introduced me to all sorts of people I had yet to meet. I loved the anticipation of waiting for film to dry after processing, stealing little glimpses of hanging negatives to see what magical moments I might have captured—to see if chance had smiled down upon me that day.

While in school I worked in various formats: 35mm, medium format (2 ¼” square), and large format (4x5”). While the portable 35mm worked best for street photography, I could still be mobile with the vintage twin lens medium format camera I used quite often, as the larger negative would yield a sharper result. The large format camera, with imperative tripod, long set-up time and endless fiddling with the bellows adjustment for focus, was cumbersome and would draw attention, particularly as I went under the dark cloth to frame and focus my subjects. Being under my dark cloth also made me susceptible to anyone who might want to mug me—we were encouraged to work in pairs but often I went out to shoot on my own in order to get unique results that would win praise from my classmates and instructors when we pinned our photographs up for critiques.

I often thought of Cartier-Bresson’s term, “The Decisive Moment,” when I was shooting. When the legendary French photographer was in the street with his camera, he was always alert, never wanting to miss that perfect moment: “One must seize the moment before it passes, the fleeting gesture, the evanescent smile… that’s why I’m so nervous… but it’s only by maintaining a permanent tension that I can stick to reality.” I too was always on high alert, camera ready, so that I might find a perfect image. Preparedness plays a large part—the right speed film loaded, camera aperture and speed set depending on your lighting conditions, and knowing where there might be some action that day. But chance is what you can’t prepare for—and you must be ready for it when it comes. I have chosen a few of my favorite photographs from my time at photography school and the years immediately following. Their visual success really relies not only upon my skills as a photographer, but just the sheer luck—and chance—of finding these subjects.

While in school I worked in various formats: 35mm, medium format (2 ¼” square), and large format (4x5”). While the portable 35mm worked best for street photography, I could still be mobile with the vintage twin lens medium format camera I used quite often, as the larger negative would yield a sharper result. The large format camera, with imperative tripod, long set-up time and endless fiddling with the bellows adjustment for focus, was cumbersome and would draw attention, particularly as I went under the dark cloth to frame and focus my subjects. Being under my dark cloth also made me susceptible to anyone who might want to mug me—we were encouraged to work in pairs but often I went out to shoot on my own in order to get unique results that would win praise from my classmates and instructors when we pinned our photographs up for critiques.

I often thought of Cartier-Bresson’s term, “The Decisive Moment,” when I was shooting. When the legendary French photographer was in the street with his camera, he was always alert, never wanting to miss that perfect moment: “One must seize the moment before it passes, the fleeting gesture, the evanescent smile… that’s why I’m so nervous… but it’s only by maintaining a permanent tension that I can stick to reality.” I too was always on high alert, camera ready, so that I might find a perfect image. Preparedness plays a large part—the right speed film loaded, camera aperture and speed set depending on your lighting conditions, and knowing where there might be some action that day. But chance is what you can’t prepare for—and you must be ready for it when it comes. I have chosen a few of my favorite photographs from my time at photography school and the years immediately following. Their visual success really relies not only upon my skills as a photographer, but just the sheer luck—and chance—of finding these subjects.

I took this photo during my first trip to Italy. In those days I carried several cameras with me, and I took this image with my vintage twin lens medium format camera by the entrance of the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II shopping arcade in Milan. I was captivated by the ornate uniforms of the Carabinieri, the Italian military police who have a presence everywhere in Italy. When I saw them chatting with the young, stylish, Italian woman I snapped the picture from a distance, trying not be noticed. I was very pleased when I returned home and processed the film, as it really captured the mood of the Italian street—crowded with the hustle and bustle of tourists, but with the everyday street conversations held by Italians at an altogether slower pace. The identical positions of the men’s hands resting on their swords, the woman’s right foot flexed up and her impossibly slim legs, the moment just before she flicks her cigarette ash, the officer who noticed me just as I clicked the shutter—there are so many elements of this image that I adore.

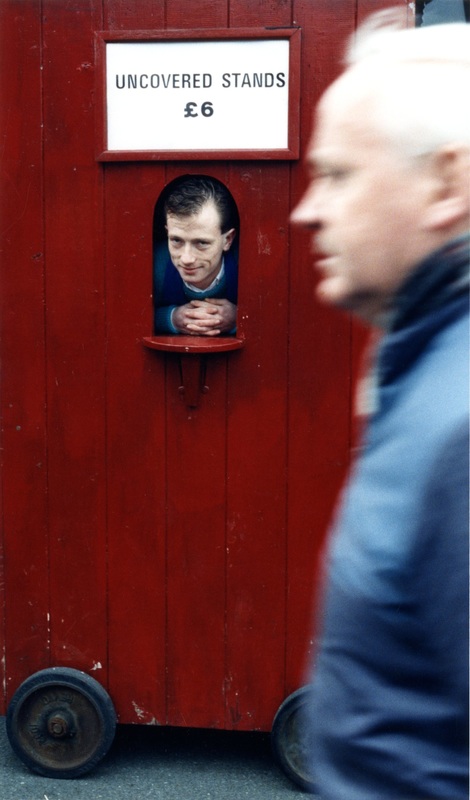

Soon after I started photography school my older sister married and moved to Ireland. I flew to Limerick to visit her and her new husband, and we drove to Dublin to catch, of all things, an American Football game: Boston College vs. Army. They were homesick and wanted to take advantage of a unique opportunity for some American sport; sitting outside on a damp November day watching football was not at all what I wanted to do, upon first landing in picturesque Ireland. I made the most of it, taking photographs with my 35mm around the crowded rugby grounds of Lansdowne Road Stadium. This ticket seller, in a tiny booth on wheels, caught my attention. I took a photo of him in the booth just as he spied me—but an elderly man passing by ruined the shot. I took another picture, thinking that the moment had passed and I moved on to other subjects. I was delighted to later find a great shot of the ticket booth that was made all the richer by the flash of a passerby, the vivid red paint, and the charismatic Irish face within.

During the first semester of photography school, we learned to use the bulky 4x5” cameras, which required the use of light readings, the understanding of exposure and composition, and required us to make very deliberate technical choices in taking photographs. We had all been using 35mm before we came to school, and employing this very old-fashioned method of photography using sheet film required us to slow down—it could take several hours to expose just a few photos. My class partner and I went to Boston’s Chinatown neighborhood, each of us taking turns with the heavy camera and tripod. While she set up her shot, I noticed this man down the block sitting on the stoop, watching us and giggling. When it was my turn to use the camera, I asked him if he would pose for me—an unusual circumstance, as the slow task of 4x5” photography is not suited for portraits. He didn’t understand me at first, as he didn’t speak English; but he soon understood what I wanted, and he gladly posed for this image. Had this shy seventeen-year-old girl not dared to ask him to pose, it never would have happened. I made a choice, and took a chance.

I later entered this image into a Kodak contest, and it won second prize. To have it published I needed my subject’s name and consent—I knocked on many doors in Chinatown, finally finding someone who recognized his face and directed me to his home. In exchange for his consent, I gave him several copies of the photo. Through an interpreter, he wrote me a letter thanking me profusely for taking such a beautiful image of him. It was one of the first images I took in photography school, and I was encouraged to continue taking people pictures.

I later entered this image into a Kodak contest, and it won second prize. To have it published I needed my subject’s name and consent—I knocked on many doors in Chinatown, finally finding someone who recognized his face and directed me to his home. In exchange for his consent, I gave him several copies of the photo. Through an interpreter, he wrote me a letter thanking me profusely for taking such a beautiful image of him. It was one of the first images I took in photography school, and I was encouraged to continue taking people pictures.

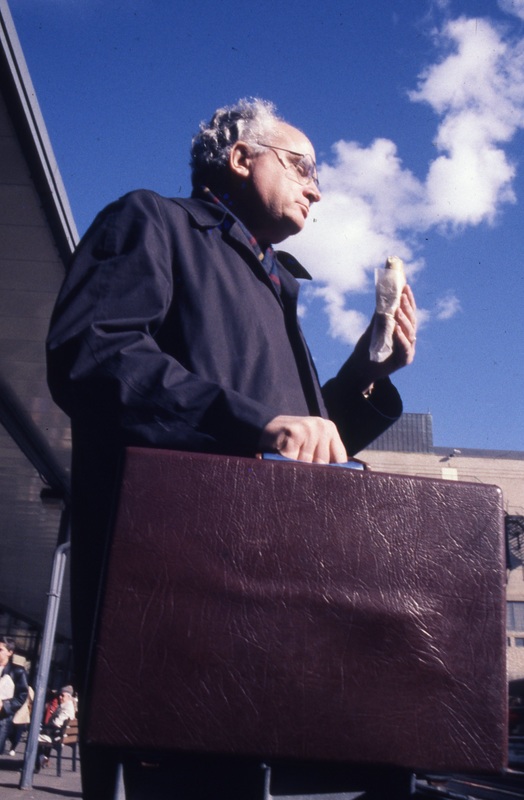

This image is one I took without really fully assessing the scene—while sitting at the train station waiting to go home, a man with a briefcase approached the bench I was sitting on, and proceeded to eat a pretzel wrapped in paper. I held my 35mm camera loaded with color slide film in my lap, guessed on angle, focus, and exposure, and quietly snapped this one picture, making sure he was not aware of what I was doing. I was hoping that the clouds would create a comical illusion of smoke coming from his snack, but I did not have any further expectations from this shot. I processed the film taken for my Color Transparencies class and determined that this image was worth including in this week’s critique. When I projected this slide on the screen, my classmates pointed out the protruding image of a gun in the briefcase. The light and shadows create the distinct shape, one that I had not seen when I snapped the photo. If it’s not a handgun, what on earth could it be? I took the photo for other reasons, but upon projection, there was so much more to talk about. Who is this man? What else is in that briefcase? Would I have dared to take the picture if I had seen, and understood, the image of the gun? Was I at all aware of the menacing angle that I had chosen, shooting the picture ‘from the hip,’ and not looking through the viewfinder? During my commute back and forth from school, I continued to look for this man, but never saw him again. What are the chances I would find him again?

These days I do not earn my living as a photographer, but I always take pictures. With the advent of digital photography and the ease with which one can take pictures with cell phones, photography has changed immensely. Social media has changed how we share photos, how we discuss them, how we look at them… even why we take them in the first place. And it’s just so easy. Instantly seeing your images, and quickly deleting the ones that you don’t like, has done away with the delightful feeling of anticipation while you wait for your film to develop, and the joy with which you pour over your contact sheets. When you delete your “mistakes,” you may miss out on details you didn’t see when you took the pictures. Images are very disposable, they’re everywhere and we don’t spend a lot of time looking at any of our own images in a meaningful way.

I don’t fight the change, and I use my iPhone far more than any other camera I own. I use social media. But I often wonder how Cartier-Bresson and his ilk would view this massive change in the medium of photography. Is it better? Or worse? Why do we take pictures now?

And if you can “fix it” in Photoshop or with Instagram filters, how much is left to chance?

These days I do not earn my living as a photographer, but I always take pictures. With the advent of digital photography and the ease with which one can take pictures with cell phones, photography has changed immensely. Social media has changed how we share photos, how we discuss them, how we look at them… even why we take them in the first place. And it’s just so easy. Instantly seeing your images, and quickly deleting the ones that you don’t like, has done away with the delightful feeling of anticipation while you wait for your film to develop, and the joy with which you pour over your contact sheets. When you delete your “mistakes,” you may miss out on details you didn’t see when you took the pictures. Images are very disposable, they’re everywhere and we don’t spend a lot of time looking at any of our own images in a meaningful way.

I don’t fight the change, and I use my iPhone far more than any other camera I own. I use social media. But I often wonder how Cartier-Bresson and his ilk would view this massive change in the medium of photography. Is it better? Or worse? Why do we take pictures now?

And if you can “fix it” in Photoshop or with Instagram filters, how much is left to chance?

Header art by T. Guzzio. Original image by the author.

CONNECT WITH CECILY:

Cecily Pollard studied photography at New England School of Photography, earned a BA in Art History from Northeastern University and expects to earn her MA in Museum Studies from Harvard University Extension School in 2016. She has never stopped loving photography, but she never really liked acid-washed jeans all that much (it was the 80’s...). You can find her on Twitter @CecilyPollard.

ADD YOUR VOICE:

ABOUT COMMENTS:

At Prodigal's Chair, thoughtful, honest interaction with our readers is important to our site's success. That's why we use Disqus as our comment / moderation system. Yes, you will need to login to leave a comment - with either your existing Facebook, Twitter, or Google+ account - or you can create your own free Disqus account. We do this for a couple of reasons: 1) to discourage trolling, and 2) to discourage spamming. Please note that Disqus will never post anything to your social network accounts unless you authorize it to do so. Finally, if you prefer you can always email comments directly to us by clicking here.