We’d like to think the chance of seeing a miracle with our own eyes (not just in a fairytale or some suspect video posted online) is minuscule, maybe even impossible. I’m a big believer in the power of narrative, but miracles seem to be a convention reserved for fairytales and scripture. Or, maybe, miracles are only seen through the eyes of those who desire to witness them? If there is a will, there is a way, I guess. There has always been a part of me that tended to be a cynic; for most of my life I fell into the pool of individuals who thought they’d never see a miracle.

Then I saw one, and so did the other 111.5 million people who watched Super Bowl XLIX.

It’s been 13 years since the New England Patriots won their first Super Bowl, and about five months since they won their last one. Both were the type of events that are stored in the special section of a sport’s fans brain which houses entire games, almost down to every detail. For those of us with this futile talent, we can recite the play-by-play action back as if it were dialogue from our favorite play.

Everyone remembers how Super Bowl XXXVI ended, or at least everyone who lives in, or is originally from New England. The St. Louis Rams had just effortlessly scored and the game was now tied. In front of Tom Brady, the team’s backup QB turned unexpected leader, there were eighty-five yards of field and eleven of the best athletes from the most sports obsessed country in the world. All he had was one minute and twenty-one seconds and no time outs. But, he had the unrelenting allegiance from a rag tag group of underappreciated nobodies, and a talented kicker who had never missed a field goal in a dome.

Then I saw one, and so did the other 111.5 million people who watched Super Bowl XLIX.

It’s been 13 years since the New England Patriots won their first Super Bowl, and about five months since they won their last one. Both were the type of events that are stored in the special section of a sport’s fans brain which houses entire games, almost down to every detail. For those of us with this futile talent, we can recite the play-by-play action back as if it were dialogue from our favorite play.

Everyone remembers how Super Bowl XXXVI ended, or at least everyone who lives in, or is originally from New England. The St. Louis Rams had just effortlessly scored and the game was now tied. In front of Tom Brady, the team’s backup QB turned unexpected leader, there were eighty-five yards of field and eleven of the best athletes from the most sports obsessed country in the world. All he had was one minute and twenty-one seconds and no time outs. But, he had the unrelenting allegiance from a rag tag group of underappreciated nobodies, and a talented kicker who had never missed a field goal in a dome.

|

What happened on the ensuing drive wasn’t a miracle. It was a very well-executed drive that took what the opposing defense gave them, which was dump passes to the Patriot’s running back J.R. Redmond, as well as a big 23-yard catch by the veteran Troy Brown which put them on the cusp of field goal range, and stopped the clock. Bill Belichick's team didn’t perform a miracle. They gave themselves a shot by implementing several high percentage plays that they knew had a chance of being successful. They created a chance by knowing their chances.

|

|

Sports are driven by statistics, more now than ever. With technology, the game has evolved. It’s no longer just about what the eye can see, but also about what a camera can record and the analytical mind can interpret. All decisions are guided by probability. Every year new statistics are created in an effort to find the best way to evaluate the players and the game. The NFL combine has become more of a collection of empirical data than what it used to be - a scouting event. Even coaches today have to be analytical in a way they never had to be in the past. Coaches used to be great personalities: you know, leaders of men. Now, a coach needs to be better at analyzing all aspects of a game at once than motivating his players. What are the chances they run a pass play? Or, what are the chances they target a certain player? What are the chances the other team blitzes? What are the chances they convert on third and seven? All this analysis is concentrated towards finding what are the chances something will happen.

|

Tom Brady and Bill Belichick after winning Super Bowl XXXVI. Photo by J. Haynes via Getty Images.

|

But, sports are contrary. They have a love affair with romance. Sports fans love the unexpected, the heroic, and better yet, the miraculous. Hope is our life force. Like I said before, I am a big believer in the power of narrative. The structure of a football season, or any sport really, is that of a novel. This is especially true when you focus the subject of the season on one team, like a main character. The games are like chapters that provide us with a plot and over arching themes. This element of romanticism is essential to the sports fan's love of the game. They really are a space, or a platform, in which stories can be constantly reinvented or renewed. And that’s why we love them because they’re familiar, but always slightly fresh and new. We watch with the dream that we will see something that we couldn’t predict, or write, on our own. We want to see something that we knew could happen, but we never thought we’d have the chance to see.

|

So in sports, there is ever-present ongoing conflict of what should happen and what could happen. What should happen is driven by probability. It’s the "right" play. It’s the play that yields an average of 5.5 yards. It’s the safe bet. It’s the play that you hesitate to make, but you feel assured by its probability of succeeding that it’s the right choice. What could happen isn’t driven by probability. It’s driven by faith. It’s the faith that the right decision has been made, even though it doesn’t seem like it, or maybe even feel like it. It’s the faith that you know what your opponent is thinking. It’s the faith that you know what happens next. But, we can’t know what happens next. The future is a mystery to us, and so sports' ongoing conflict goes unsettled as we battle the idea of knowing we don’t know the future, but hoping that we do.

The final play of Super Bowl XLIX has been analyzed, dissected, and critiqued by millions of people, some of who are considered experts in the field of football gameplay and decision-making. It’s been deemed a "heads up" play, a result of the Patriot’s game planning, and as a result of Malcolm Butler’s willingness to submit to his fundamentals. It’s also been called a result of bad play calling on the part of Pete Carroll, the Seattle Seahawks' coach, who probably should have given the ball his best player, Marshawn Lynch, AKA "Beast Mode." I can buy these explanations, but when I do I am still left mostly unsatisfied because that is not how I experienced it.

To me, that play was a miracle.

To me, that play was a miracle.

Actually, the miraculous play had already happened. Jermaine Kearse had caught a ball on his ass. A ball that Butler had swatted out of his hands, with his body fully extended, and still somehow fell into Kearse's lap, like a gift from God. As the Seahawks marched down the field and sat merely one yard between themselves and victory, I kneeled before the television hoping that something would happen, but knowing that the chances were not in our favor.

We were about to lose. No, we were going to lose. Actually we had already lost.

We were about to lose. No, we were going to lose. Actually we had already lost.

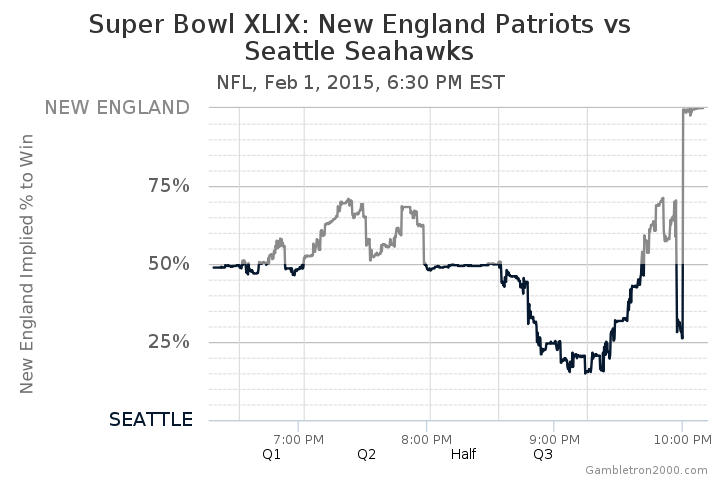

At that point, the chance that the Patriots would win was, statistically speaking, very small. But they could still win. And when I thought about whether or not they could win, the numbers didn’t matter, all it took was a slight chance. That sliver of hope was enough to hold up the validity of that phrase, "they still could still win it."

Malcolm Butler was an undrafted free agent that grinded his way onto the Patriots' roster. On a team that had one of the deepest defensive backfields in football (a miracle in its own right considering the Patriots history with defensive backs) this rookie had made it on the team through his work ethic and a full submission to his fundamentals. He was the kind of guy that Belicheck could fall in love with.

Malcolm Butler was an undrafted free agent that grinded his way onto the Patriots' roster. On a team that had one of the deepest defensive backfields in football (a miracle in its own right considering the Patriots history with defensive backs) this rookie had made it on the team through his work ethic and a full submission to his fundamentals. He was the kind of guy that Belicheck could fall in love with.

They could still win it, but they shouldn’t have. The Seahawks probably should have lined up and shoved Marshawn Lynch down the throats of the Patriots defensive line, but they didn’t. The Patriots lined up in goal line, thinking that the Seahawks would run. That led the Seahawks to run a slant, thinking "we’ll take our chances against an unproven rookie corner who just botched the biggest play of the game instead of running into three Pro Bowl defensive linemen." It was a choice that was self-assured. It was more probable than not that Butler would not be able to make a play on the ball. It was more probable than not that the Seahawks would have another shot at the end zone if the play fizzled out. It was more probable than not that the Seahawks would win, and the Patriots would lose. But, what is probable is never certain.

Earlier this month, Ted Wells, an attorney hired by the NFL to investigate whether or not the Patriots had deflated game balls for the AFC Championship game, released a 243 page report that concluded it was "more probable than not that New England Patriots personnel participated in violations of the Playing Rules and were involved in a deliberate effort to circumvent the rules," and that, "it is more probable than not that Tom Brady. . . was at least generally aware of the inappropriate activities of. . . the release of air from Patriots game balls."

This report has reinforced the notion that the New England Patriots have not only cheated, but are and have been reoccurring cheaters in the NFL. It’s assumed that the Patriots are the type of organization that is incredibly knowledgeable of the rules of football and therefore constantly look for ways to reinterpret them to gain competitive advantages (or increase their own probability of winning) over their opponents. So, it’s said that there is a chance that the Patriots made the choice to cheat in a game that they won handedly, and because of that they haven’t truly earned the right to be considered a deserved champion.

As a Patriot’s fan, the news of Deflategate and the Wells Report has left me unsettled. It leaves a gloomy cloud of doubt over a miraculous act of who knows what. Maybe it was an act of God, destiny, probability, or just plain luck. But, what if the path to that moment was created out of deception and dishonesty? What if Tom Brady did know that game balls were deflated and he asked for them to be that way? Even if I think he didn't, I know that there is still a chance that he did.

The situation is suspect, but what it really is, is a test of faith. What do I choose to believe, and what is the reasoning? Do I choose to believe in the facts that sway towards the thinking that Brady and the Patriots probably knew what was happening and turned a blind eye to the matter, or do I put faith in them, blindly, as I think about how I doubted them before when they were on the one yard line and they proved that all you need is a sliver of hope to believe that something can have a chance of happening. Just how Malcolm Butler’s miraculous interception to save the Patriots late game lead was not probable, it happened. I know that part of me is a cynic, but this time that sliver is enough for me to doubt what is probable.

Earlier this month, Ted Wells, an attorney hired by the NFL to investigate whether or not the Patriots had deflated game balls for the AFC Championship game, released a 243 page report that concluded it was "more probable than not that New England Patriots personnel participated in violations of the Playing Rules and were involved in a deliberate effort to circumvent the rules," and that, "it is more probable than not that Tom Brady. . . was at least generally aware of the inappropriate activities of. . . the release of air from Patriots game balls."

This report has reinforced the notion that the New England Patriots have not only cheated, but are and have been reoccurring cheaters in the NFL. It’s assumed that the Patriots are the type of organization that is incredibly knowledgeable of the rules of football and therefore constantly look for ways to reinterpret them to gain competitive advantages (or increase their own probability of winning) over their opponents. So, it’s said that there is a chance that the Patriots made the choice to cheat in a game that they won handedly, and because of that they haven’t truly earned the right to be considered a deserved champion.

As a Patriot’s fan, the news of Deflategate and the Wells Report has left me unsettled. It leaves a gloomy cloud of doubt over a miraculous act of who knows what. Maybe it was an act of God, destiny, probability, or just plain luck. But, what if the path to that moment was created out of deception and dishonesty? What if Tom Brady did know that game balls were deflated and he asked for them to be that way? Even if I think he didn't, I know that there is still a chance that he did.

The situation is suspect, but what it really is, is a test of faith. What do I choose to believe, and what is the reasoning? Do I choose to believe in the facts that sway towards the thinking that Brady and the Patriots probably knew what was happening and turned a blind eye to the matter, or do I put faith in them, blindly, as I think about how I doubted them before when they were on the one yard line and they proved that all you need is a sliver of hope to believe that something can have a chance of happening. Just how Malcolm Butler’s miraculous interception to save the Patriots late game lead was not probable, it happened. I know that part of me is a cynic, but this time that sliver is enough for me to doubt what is probable.

Header art by T. Guzzio. Original photo by T. Clary via Getty Images.

CONNECT WITH NATE:

Nate Sousa is freshly graduated from Lake Forest College, just north of Chicago. He is a Boston sports fan suffering in exile. His writing tends to focus on what he is passionate about, like sports and his family. Nate used to run, but still listens to, an independent radio station in Lake Forest, WMXM 88.9FM, and he strongly suggests that you do, too. You can follow him on Twitter @ohheynate.

ADD YOUR VOICE:

ABOUT COMMENTS:

At Prodigal's Chair, thoughtful, honest interaction with our readers is important to our site's success. That's why we use Disqus as our comment / moderation system. Yes, you will need to login to leave a comment - with either your existing Facebook, Twitter, or Google+ account - or you can create your own free Disqus account. We do this for a couple of reasons: 1) to discourage trolling, and 2) to discourage spamming. Please note that Disqus will never post anything to your social network accounts unless you authorize it to do so. Finally, if you prefer you can always email comments directly to us by clicking here.