When all the rivers are used, when all the creeks in the ravines, when all the brooks, when all the springs are used... there is still not sufficient water to irrigate all this arid land.

- John Wesley Powell to the 1893 Los Angeles International Irrigation Conference

The Colorado River Basin. Map via the USGS National Map Project.

The Colorado River Basin. Map via the USGS National Map Project.

The Colorado is the iconic river of the American West. From its headwaters nearly 10,000 feet above sea level in the Rocky Mountains to its delta at the Gulf of California, the Colorado River traverses 1,450 miles of mountains, highlands, deserts and canyons. Famed for its whitewater thrills, scenic wonder, and of course its 280 mile stretch cutting through the Grand Canyon, the river is a source of grandeur, inspiration and recreation… But it is so much more.

To flora and fauna alike, as well as to over 40 million people spread across a thousand miles of arid landscape, the Colorado River is life itself. Drinking water and irrigation from the river flows to seven states according to the Colorado River Compact, an agreement born in 1922. The allocations agreed upon and stated in the Compact were based on a short term analysis of flow rate; and, worthy of note, that analysis took place during particularly wet years. Consequently, more water is allocated from the river than there is actual available water. Sadly, the Colorado River does not make its way to sea any longer. The Colorado River Delta exists in name only, but the river runs dry at its southern terminus. The once mighty Colorado is now known as a “deficit river” — as if there was something wrong with the river itself, as opposed to the overallocation laid onto the river by need, political will, and ignorance.

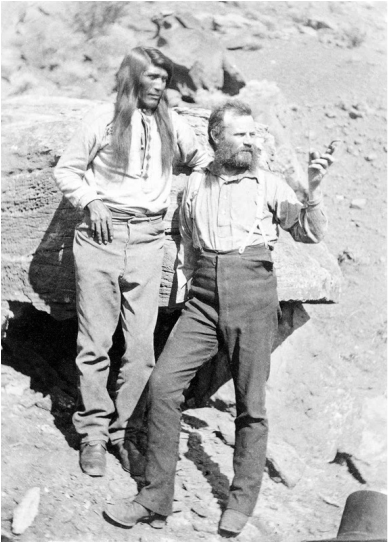

A warning was voiced as early as 1870 about settling the lands within the Colorado River’s watershed, and across all of the arid west for that matter. Civil War hero Major John Wesley Powell, who had lost one arm at the battle of Shiloh, was a self taught geologist and held a strong interest in Native American culture. He cofounded the National Geographic Institute as well as the Bureau of Ethnography at the Smithsonian Institute. Additionally, Powell served as the second director of the United States Geologic Survey.

To flora and fauna alike, as well as to over 40 million people spread across a thousand miles of arid landscape, the Colorado River is life itself. Drinking water and irrigation from the river flows to seven states according to the Colorado River Compact, an agreement born in 1922. The allocations agreed upon and stated in the Compact were based on a short term analysis of flow rate; and, worthy of note, that analysis took place during particularly wet years. Consequently, more water is allocated from the river than there is actual available water. Sadly, the Colorado River does not make its way to sea any longer. The Colorado River Delta exists in name only, but the river runs dry at its southern terminus. The once mighty Colorado is now known as a “deficit river” — as if there was something wrong with the river itself, as opposed to the overallocation laid onto the river by need, political will, and ignorance.

A warning was voiced as early as 1870 about settling the lands within the Colorado River’s watershed, and across all of the arid west for that matter. Civil War hero Major John Wesley Powell, who had lost one arm at the battle of Shiloh, was a self taught geologist and held a strong interest in Native American culture. He cofounded the National Geographic Institute as well as the Bureau of Ethnography at the Smithsonian Institute. Additionally, Powell served as the second director of the United States Geologic Survey.

Powell in 1871 with Tau-gu of the Paiute tribe. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Powell in 1871 with Tau-gu of the Paiute tribe. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

In 1869 Powell became the first systematic explorer of the Colorado River, and with his small band of men in four wooden boats, led the first recorded party though Grand Canyon naming many of the river’s features along the way, including Grand Canyon itself. Beginning in Green River, Wyoming, Powell’s party endured the searing heat, dreadful cold, and horrific whitewater. They lost a boat, as well as three crew members who decided they’d rather try walking out of the Grand Canyon (and were subsequently killed) rather than face another day on the river. Still, Powell’s small group completed their explorations and exited the Grand Canyon under their own power having mapped the river and its tributaries extensively.

Powell would return in 1871 to gather significantly more data, and ultimately publish an account of both journeys under the title The Exploration of the Colorado River and its Canyons. Through his work Powell understood the significance of the river and issued stern warnings about the area’s habitability which went unheeded. The Major was clear that settling the region of the Colorado River, and indeed much of the West, was folly due to the aridity of the landscape.

Powell went on record stating the American West, with minute exception, was completely unsuitable for any type of agriculture and settlement. This assessment, drawn from data taken during the expeditions, was of course ahead of its time. Post Civil War America basked in the idea of Manifest Destiny, desirous of spreading out coast to coast, and the Major’s ideas of conservation did not fit in such a model. Concurrently, the railroad industry lobbied hard in Congress for a western push into expansive agriculture —this is what would bring the people out west, they argued in Washington. A decade earlier large tracts of land had been traded from the US government to the railroads in exchange for laying the track, and with that track laid down came the opportunity for the railroads to cash in. Western expansion had begun despite Powell’s visionary testimony to Congress on numerous occasions.

The Congress had initially appeared to consider both sides of the issue, investigating what if any impact populating the West may have and ultimately decided Powell had the science wrong. Congress rested its decisions regarding the population of the West on a scientific theory promoting agriculture as a means of favorably changing the climate of the region. The phrase, “the rain will follow the plow” — a view no doubt embraced by the railroads — came into favor. Of course, nearly a century and a half later the climate has not changed to favor agriculture, and the politics of water rages on. Speaking in 1893 at a conference focussed on irrigation and western settlement Powell warned, “Gentlemen, you are piling up a heritage of conflict and litigation over water rights, for there is not sufficient water to supply the land.” These words are certainly haunting today.

Powell would return in 1871 to gather significantly more data, and ultimately publish an account of both journeys under the title The Exploration of the Colorado River and its Canyons. Through his work Powell understood the significance of the river and issued stern warnings about the area’s habitability which went unheeded. The Major was clear that settling the region of the Colorado River, and indeed much of the West, was folly due to the aridity of the landscape.

Powell went on record stating the American West, with minute exception, was completely unsuitable for any type of agriculture and settlement. This assessment, drawn from data taken during the expeditions, was of course ahead of its time. Post Civil War America basked in the idea of Manifest Destiny, desirous of spreading out coast to coast, and the Major’s ideas of conservation did not fit in such a model. Concurrently, the railroad industry lobbied hard in Congress for a western push into expansive agriculture —this is what would bring the people out west, they argued in Washington. A decade earlier large tracts of land had been traded from the US government to the railroads in exchange for laying the track, and with that track laid down came the opportunity for the railroads to cash in. Western expansion had begun despite Powell’s visionary testimony to Congress on numerous occasions.

The Congress had initially appeared to consider both sides of the issue, investigating what if any impact populating the West may have and ultimately decided Powell had the science wrong. Congress rested its decisions regarding the population of the West on a scientific theory promoting agriculture as a means of favorably changing the climate of the region. The phrase, “the rain will follow the plow” — a view no doubt embraced by the railroads — came into favor. Of course, nearly a century and a half later the climate has not changed to favor agriculture, and the politics of water rages on. Speaking in 1893 at a conference focussed on irrigation and western settlement Powell warned, “Gentlemen, you are piling up a heritage of conflict and litigation over water rights, for there is not sufficient water to supply the land.” These words are certainly haunting today.

The time is far too late for heeding the words of Major John Wesley Powell and staying out of the West. The arid lands of the American West are fully populated and that population is booming. With golf courses in the Phoenix desert, beautifully manicured lawns across Salt Lake City, and magnificent hydro-electric powered neon in Las Vegas, it is clear we as a nation misuse our water resources every day. As the demand for precious water across the West continues to soar, the time is well past — yet of the essence — for us to embrace robust conservation strategies, newer technologies for waste reduction, and solar power as a means to reduce dependence on fossil fuel and hydro power.

But without political will this paradigm shift is unlikely to take place. Voters must embrace green solutions to environmental issues plaguing the nation and the globe. In the American West, there is some irony to be found in this regard because of the seven states in the Colorado River Compact only blue California tends to side with environmental policy favoring green technologies. Red states such as Utah and Arizona, in the heart of Colorado River corridor, have historically eschewed progressive environmental policy in favor of oil, mining and natural gas interests. Additionally, senators from these states refuse to acknowledge negative trends in climate change despite 99% of the scientific community being in agreement about the reality of global warming. It is this type of thinking, and the refusal to embrace the science on the table, which allowed the railroads to sell young America on the notion Major John Wesley Powell aggressively refuted, that somehow the plow would bring the rain.

But without political will this paradigm shift is unlikely to take place. Voters must embrace green solutions to environmental issues plaguing the nation and the globe. In the American West, there is some irony to be found in this regard because of the seven states in the Colorado River Compact only blue California tends to side with environmental policy favoring green technologies. Red states such as Utah and Arizona, in the heart of Colorado River corridor, have historically eschewed progressive environmental policy in favor of oil, mining and natural gas interests. Additionally, senators from these states refuse to acknowledge negative trends in climate change despite 99% of the scientific community being in agreement about the reality of global warming. It is this type of thinking, and the refusal to embrace the science on the table, which allowed the railroads to sell young America on the notion Major John Wesley Powell aggressively refuted, that somehow the plow would bring the rain.

Header art by T. Guzzio. Original photo via Paul Herman / Wikipedia Commons

CONNECT WITH CHRISTOPHER:

Christopher Mattera, Ed.D. has been descending and photographing technical canyons on the Colorado Plateau for twenty-five years. His photography appears in Moab Canyoneering: Exploring Technical Canyons Around Moab, the newest guide book to technical canyoneering on the Colorado Plateau, recently published by Sharp End Publications. In addition he is an educator, and writer. Contact Chris at [email protected].

ADD YOUR VOICE:

ABOUT COMMENTS:

At Prodigal's Chair, thoughtful, honest interaction with our readers is important to our site's success. That's why we use Disqus as our comment / moderation system. Yes, you will need to login to leave a comment - with either your existing Facebook, Twitter, or Google+ account - or you can create your own free Disqus account. We do this for a couple of reasons: 1) to discourage trolling, and 2) to discourage spamming. Please note that Disqus will never post anything to your social network accounts unless you authorize it to do so. Finally, if you prefer you can always email comments directly to us by clicking here.