July 19, 2016, Donner Memorial State Park, Truckee, CA: It’s a perfect summer morning high in the Sierra Nevada, the kind of pristine locale (elevation 6,000 feet) where even naturalist John Muir might need to pinch himself to see if he was awake. Families on bicycles pull up at the visitor center to use the bathroom and fill their water bottles. A cool creek fed by the mountain snow pack winds among towering pines that smell warm in the sunshine. A couple with a dog take it easy in beach chairs in the middle of the creek. He smokes a cigar and the water trickles around their ankles. Campers emerge from their tents to cool their toes in the crystalline water and see what this placid morning will bring. Kids prod feisty crawfish in a bucket. We hike lazily to the place where the creek meets a shimmering blue lake. People swim and play on floats, kayaks and paddle boards. Our son, Abe, tries a little fishing. Our daughter, Alaina, braves the chilly water of the creek. A steady wind blows from the west. Trouble is nowhere.

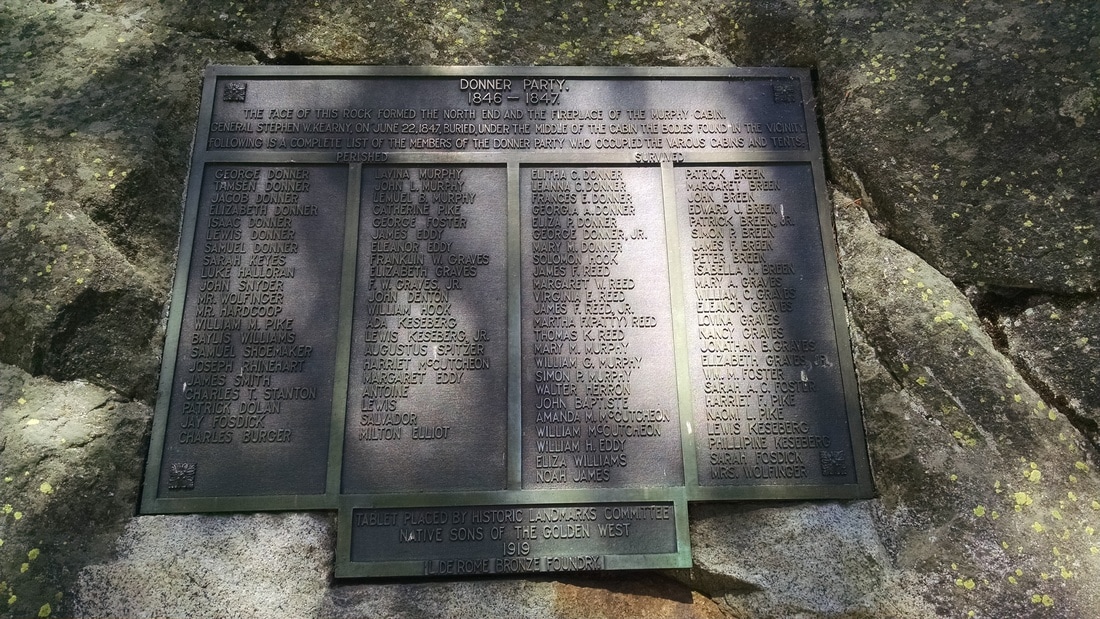

October 28, 1846, same spot: Heavy snowfall blocks the mountain pass just as a group of pioneers known as the Donner Party arrives in the Sierras. In April, the Donner family, along with the Reeds, Murphys, Graveses, and others had set out from Springfield, IL, to do what pioneers do – establish a better life out West. They’ve followed some bad directions, made some unwise decisions, fallen into fighting and bickering, and wind up in the high Sierras just as the unusually harsh winter sets in. Rescue attempts are made, but much of the party hunkers down in cabins, where rations dwindle. They dig the bodies of their frozen oxen out of the snow and shoot a grizzly, but ultimately they run out of food. As members of the group perish, some of the survivors take part in an unthinkable act, eating the flesh of their dead companions to live. Only 45 of the 89 emigrants make it out of the mountains alive. In June, passing through with his company, Gen. Stephen Kearny finds the remains of those who did not survive the winter's horrors. He digs a hole in the center of the Murphy cabin, buries the bodies and all that is associated with them, and burns it to the ground.

October 28, 1846, same spot: Heavy snowfall blocks the mountain pass just as a group of pioneers known as the Donner Party arrives in the Sierras. In April, the Donner family, along with the Reeds, Murphys, Graveses, and others had set out from Springfield, IL, to do what pioneers do – establish a better life out West. They’ve followed some bad directions, made some unwise decisions, fallen into fighting and bickering, and wind up in the high Sierras just as the unusually harsh winter sets in. Rescue attempts are made, but much of the party hunkers down in cabins, where rations dwindle. They dig the bodies of their frozen oxen out of the snow and shoot a grizzly, but ultimately they run out of food. As members of the group perish, some of the survivors take part in an unthinkable act, eating the flesh of their dead companions to live. Only 45 of the 89 emigrants make it out of the mountains alive. In June, passing through with his company, Gen. Stephen Kearny finds the remains of those who did not survive the winter's horrors. He digs a hole in the center of the Murphy cabin, buries the bodies and all that is associated with them, and burns it to the ground.

Reaching Donner State Park was a sort of triumph on our own westward journey last summer. After months of planning, our family loaded all our necessities into a 26-year-old Chevy camper and made a continental circuit that would ultimately cover 23 states, 13 parks and museums, and more than 9,000 miles in 31 days. Making the RV livable and drivable was a feat in itself; our adventure barely made it off the ground on the designated day. As we drove west, the landscape changing from rolling hills to flat cornfields to scraggly cow pastures and back, I felt a kinship with the pioneers who went generations before me. Ours was a covered wagon of sorts, bearing everything our party of four would need to survive a month on the road. The family dynamic was difficult at times. Our son and daughter turned 12 and 10, respectively, along the way. We celebrated their birthdays at campgrounds. The road was no obstacle. Life surged forward. We were drawn west by the lure of discovery, always cognizant of the what-ifs. A camper has all the systems of a house – plumbing, AC, kitchen appliances, LP gas, etc. – plus those you find in any automobile. Though we had gone through everything carefully and replaced worn and broken parts, at 26 years old any of those systems could fail at any time. A small failure might result in an inconvenience – say, not being able to cook or shower. A big failure would be journey-ending. But with a box of tools and spare parts – and a Good Sam membership in case the need for a tow should arise – we persisted.

We arrived at Donner Park in a splendid mood, bolstered by the feeling that we had accomplished something great. We had done it – we had reached California; we had made it coast to coast. The what-ifs faded; no looming breakdown could take this away from us. After a stop in the museum, where we watched a video on the Donner catastrophe and toured exhibits that commemorated their doomed layover, we headed out to the trails. Our nature walk brought us to a big boulder in the woods with a metal plaque that memorializes those who died as well as those who survived. This boulder, the plaque explains, was one wall of the Murphy cabin. Reading the plaque on this perfect summer day, I realized we were standing on a grave. The feeling of this place was at once peaceful and somber. Here we were, joyful, vibrant, breathing in the sun-warmed air, lulled by the sense of satisfaction only nature and achievement can provide. Yet in the layers beneath lay those whose experience was the exact opposite. They must have been gripped by dread and regret as they took their final gasps of crisp mountain air, nestled somewhere in the 20-foot snow pack, reduced to skeletons. To us, Donner State Park represented a triumph. For them, the mountain pass was the worst decision of their lives. Yet somehow, both realities existed in the same spot, on the same mountain, separated only by time. Separated by seasons.

This is how we survive – in layers upon layers, seasons upon seasons, epochs upon epochs. Each generation looks to its own frontier. Some reach it; others fall just short, though their efforts are not in vain.

This is how we survive – in layers upon layers, seasons upon seasons, epochs upon epochs. Each generation looks to its own frontier. Some reach it; others fall just short, though their efforts are not in vain.

All photos by the author. Header art by T. Guzzio.

CONNECT WITH BEN:

Ben Adelman, an English teacher and sometimes newspaper editor, is related to the Graves family, though not directly descended from those Graveses who perished in Donner Pass. Email him at [email protected]. Learn more on the Donner Party here.

ADD YOUR VOICE:

ABOUT COMMENTS:

At Prodigal's Chair, thoughtful, honest interaction with our readers is important to our site's success. That's why we use Disqus as our comment / moderation system. Yes, you will need to login to leave a comment - with either your existing Facebook, Twitter, or Google+ account - or you can create your own free Disqus account. We do this for a couple of reasons: 1) to discourage trolling, and 2) to discourage spamming. Please note that Disqus will never post anything to your social network accounts unless you authorize it to do so. Finally, if you prefer you can always email comments directly to us by clicking here.