Revere, Massachusetts, a city north of and adjacent to Boston, is home to a three mile crescent of sandy beach, which was the first public beach in the country. A mile from my childhood home was the scene of the first naval battle of the American Revolution, and second overall battle. Locals and patriots from across New England took control of the HMS Diana on what is now known as Chelsea Creek and looted then burned her down. The graveyard behind the local library (which was a gift from Andrew Carnegie) honors the remains of a spectrum of citizenry including servants, tradespeople, and the powerful and influential. Amusements and attractions on Revere Beach during the period of 1900s to the 1960s earned it the nickname, “Coney Island of New England,” and it boasted three arguably world class, spectacularly designed roller coasters, a run of boardwalk, a popular bandstand still used today, and a ballroom extending out into the waters. Today Revere boasts outstanding schools, multicultural neighborhoods, rapid access to jobs and businesses associated with the state’s capital city, and honest hardworking people striving to provide the best for their families. This is a brief history of Revere, my Hometown.

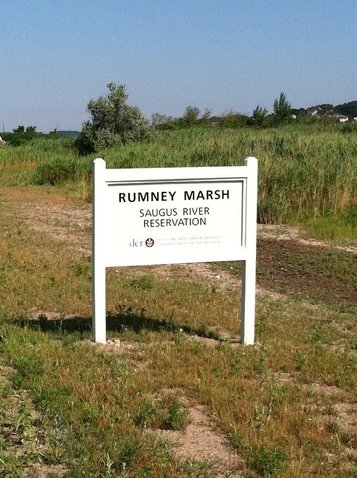

RUMNEY MARSH: THE EARLIEST SETTLERS

Photo: Saugus River Watershed Council.

Photo: Saugus River Watershed Council.

The landscape which grew into Revere was originally known to its earliest European settlers as Rumney Marsh. Prior to 1600 little by way of a historical record is available for the area, however it is known Native American people inhabited the region. Relics and archaeological evidence has been located at many sites across the city, including a tribal burying ground located along current day Revere Street in the neighborhood of Saint Anthony’s Church. The so-called Rumney Marsh Indians, whose land extended beyond the boundaries of modern day Revere into neighboring cities and towns north of the Charles River, were subjects under the leadership of two brothers named Sagamore John and Sagamore James. By 1617 many of the tribe were destroyed by warfare and illness. A plague swept across the region, and the Rumney Marsh Indians did not fare well. From that point forward, Sagamore John controlled his people in the region that today comprises the cities of Revere, Chelsea, East Boston and Winthrop. His brother, Sagamore James, controlled the areas now known as Lynn and Salem.

The first permanent settlement near Boston Harbor involved the work of Samuel Maverick. Later, in 1631 the first ferry in New England and perhaps North America was established, crossing Boston Harbor from Boston to Charlestown to Winnisimmet (Chelsea/Revere). Sam Maverick was one of the men running the Winnisimmet Ferry Company. Modern day Maverick Station, on the T’s Blue Line, located on the Chelsea side of Boston Harbor, commemorates the Maverick’s contributions to the area.

Samuel Maverick had a brother, Elias, who moved from Charlestown to Winnisimmet in the early 1620s. It is likely he was the first white settler in the region of Rumney Marsh. Elias Maverick formed an allegiance with Sagamore John, and befriended the Rumney Marsh Indians. Their coexistence was peaceful and in 1633 when a small pox epidemic struck the Indians, Elias Maverick was among those helping to bury the dead tribespeople. Indeed, Maverick is believed to have buried his friend Sagamore John during this time.

The Rumney Marsh Indians were hunters and gatherers who subsisted largely on fishing. The skills and knowledge base they shared with white settlers in the vicinity of Rumney Marsh was invaluable and allowed these newcomers the opportunity to survive and to thrive. As a runner I have often enjoyed running the trails at the Belle Isle Reservation located in Revere and East Boston. The landscape, one of salt marsh estuary and tidal creeks, is where our earliest settlers drew subsistence. From any vantage point along the trails or walking paths at Belle Isle I have found it is easy to imagine more primitive times, when Revere was known as Rumney Marsh, and Native Americans and hearty settlers coexisted together, laying down the roots from which the city of Revere would grow.

The first permanent settlement near Boston Harbor involved the work of Samuel Maverick. Later, in 1631 the first ferry in New England and perhaps North America was established, crossing Boston Harbor from Boston to Charlestown to Winnisimmet (Chelsea/Revere). Sam Maverick was one of the men running the Winnisimmet Ferry Company. Modern day Maverick Station, on the T’s Blue Line, located on the Chelsea side of Boston Harbor, commemorates the Maverick’s contributions to the area.

Samuel Maverick had a brother, Elias, who moved from Charlestown to Winnisimmet in the early 1620s. It is likely he was the first white settler in the region of Rumney Marsh. Elias Maverick formed an allegiance with Sagamore John, and befriended the Rumney Marsh Indians. Their coexistence was peaceful and in 1633 when a small pox epidemic struck the Indians, Elias Maverick was among those helping to bury the dead tribespeople. Indeed, Maverick is believed to have buried his friend Sagamore John during this time.

The Rumney Marsh Indians were hunters and gatherers who subsisted largely on fishing. The skills and knowledge base they shared with white settlers in the vicinity of Rumney Marsh was invaluable and allowed these newcomers the opportunity to survive and to thrive. As a runner I have often enjoyed running the trails at the Belle Isle Reservation located in Revere and East Boston. The landscape, one of salt marsh estuary and tidal creeks, is where our earliest settlers drew subsistence. From any vantage point along the trails or walking paths at Belle Isle I have found it is easy to imagine more primitive times, when Revere was known as Rumney Marsh, and Native Americans and hearty settlers coexisted together, laying down the roots from which the city of Revere would grow.

THE BATTLE OF CHELSEA CREEK

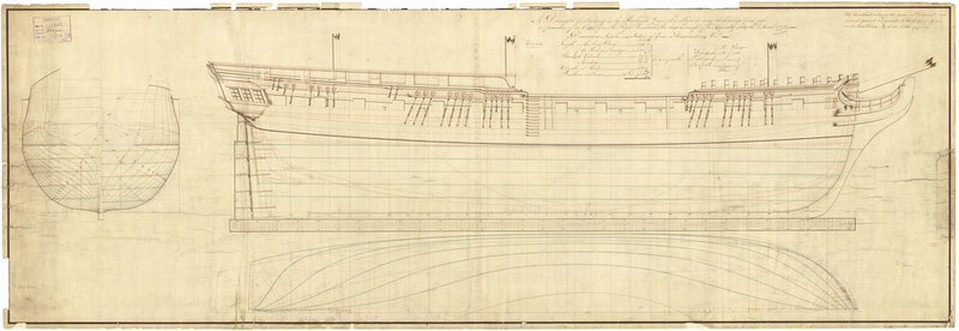

Map of Chelsea Creek. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Map of Chelsea Creek. Via Wikimedia Commons.

When you were in grade school chances are good you learned about the American Revolution. Likely you studied the first battle of the Revolutionary War, The Battle of Lexington and Concord. Just as likely you have heard of the third battle of the war, The Battle of Bunker Hill. Very few, however, can identify the second battle of the American Revolutionary War despite its impact and significance to the rebel cause.

Seemingly obscured by the history books, the Battle of Chelsea Creek was the second battle of the American Revolution, and the first naval battle. The battle was fought on Chelsea Creek, a marshy, ocean-inlet whose waters rise and lower with each successive tide, and only about a mile stroll from my childhood home. Chelsea Creek is located along the Revere/Chelsea town line, and in areas the waterway itself forms the town line. In current times the creek has been encroached upon by urban sprawl, and a highway (Revere Beach Parkway, Route 16) runs through it. It would not be too difficult, though, to imagine a time when nary a structure was present and a vast wilderness of salt marsh estuary blanketed the coastal edge of this region, inhabited mainly by wildlife, and some wild-eyed musket-wielding revolutionaries committed to carving out a nation of and by the people.

On May 27th of 1775, not long after the first battle of the American Revolution was fought on the greens and bridges of Lexington and Concord, the HMS Diana chased colonist patriots up the Chelsea Creek away from Noddles Island (the present-day Beachmont section of Revere) and Hog Island (which is the Orient Heights section of East Boston today) where the Americans were attempting to remove all provisions the British relied on. In essence, the young patriots were attempting to starve the British out of Boston. It was good strategy and the British soon took notice.

Sometime in the mid afternoon the British spied smoke from Noddles Island and recognized it immediately for what it was. After absconding with all of the livestock they could handle, the colonists had set fire to a house and barn on the island, following through on their mission to destroy anything they could not consume or carry with them. The colonists’ plan was working to some degree. On this particular afternoon, however, the British Navy was in quick pursuit of the colonists. The HMS Diana, a schooner purchased by the British in North America from a British loyalist living in Weymouth, sailed up Chelsea Creek in an attempt to cut off the patriots, reclaim the stolen livestock, and make public examples of the American rebels. It was not so easily accomplished, the Diana’s crew soon found out.

Over 300 militia men, representing at least three colonies had come together under the command of Colonel John Stark* and Colonel John Nixon*, both of New Hampshire, and Israel Putnam* from Connecticut. They dug in at various points along the Creek, hidden in the reeds of the salt marsh, and energized by the desire for freedom and liberation from England. Strong and confident, the colonists battled valiantly against the powerful English Navy.

Captained by Lieutenant William Graves, the Diana and the patriots exchanged fire for several hours. At about 8pm with the tide quickly lowering, Graves found himself in a precarious situation and ordered crew members out to the Diana’s longboats in an effort to help redirect the battleship. What Graves needed was a u-turn and fast, for the Diana was in a narrow channel and the watercourse ahead was tighter still. The British marines who oared those longboats did so under heavy fire from the colonists. It is reported two British longboat oarsmen were killed, with several others wounded.

Despite the efforts of the British sailors to turn the ship around and retreat out to Boston Harbor, the Diana was caught in the mud flats as the tide withdrew shortly before dark. Graves ordered the ship be stabilized and for a short while the British were able to continue to fight the colonists from her stationary position. The stabilization did not last long, however, as the mud in the marshes and estuaries surrounding Boston, then as now, is boggy and consuming in its effect, and the HMS Diana rolled over. Now, on her beam ends, the Diana was useless to the British as they could not keep to the deck, nor could they fire the guns. Around 10pm Graves ordered the Diana abandoned.

Sometime around midnight the revolutionaries boarded the British vessel, looted her to the core, and burned her down. The munitions taken from the Diana, including canons and swivel guns, as well as ammunition were used against the British a short time later at the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Seemingly obscured by the history books, the Battle of Chelsea Creek was the second battle of the American Revolution, and the first naval battle. The battle was fought on Chelsea Creek, a marshy, ocean-inlet whose waters rise and lower with each successive tide, and only about a mile stroll from my childhood home. Chelsea Creek is located along the Revere/Chelsea town line, and in areas the waterway itself forms the town line. In current times the creek has been encroached upon by urban sprawl, and a highway (Revere Beach Parkway, Route 16) runs through it. It would not be too difficult, though, to imagine a time when nary a structure was present and a vast wilderness of salt marsh estuary blanketed the coastal edge of this region, inhabited mainly by wildlife, and some wild-eyed musket-wielding revolutionaries committed to carving out a nation of and by the people.

On May 27th of 1775, not long after the first battle of the American Revolution was fought on the greens and bridges of Lexington and Concord, the HMS Diana chased colonist patriots up the Chelsea Creek away from Noddles Island (the present-day Beachmont section of Revere) and Hog Island (which is the Orient Heights section of East Boston today) where the Americans were attempting to remove all provisions the British relied on. In essence, the young patriots were attempting to starve the British out of Boston. It was good strategy and the British soon took notice.

Sometime in the mid afternoon the British spied smoke from Noddles Island and recognized it immediately for what it was. After absconding with all of the livestock they could handle, the colonists had set fire to a house and barn on the island, following through on their mission to destroy anything they could not consume or carry with them. The colonists’ plan was working to some degree. On this particular afternoon, however, the British Navy was in quick pursuit of the colonists. The HMS Diana, a schooner purchased by the British in North America from a British loyalist living in Weymouth, sailed up Chelsea Creek in an attempt to cut off the patriots, reclaim the stolen livestock, and make public examples of the American rebels. It was not so easily accomplished, the Diana’s crew soon found out.

Over 300 militia men, representing at least three colonies had come together under the command of Colonel John Stark* and Colonel John Nixon*, both of New Hampshire, and Israel Putnam* from Connecticut. They dug in at various points along the Creek, hidden in the reeds of the salt marsh, and energized by the desire for freedom and liberation from England. Strong and confident, the colonists battled valiantly against the powerful English Navy.

Captained by Lieutenant William Graves, the Diana and the patriots exchanged fire for several hours. At about 8pm with the tide quickly lowering, Graves found himself in a precarious situation and ordered crew members out to the Diana’s longboats in an effort to help redirect the battleship. What Graves needed was a u-turn and fast, for the Diana was in a narrow channel and the watercourse ahead was tighter still. The British marines who oared those longboats did so under heavy fire from the colonists. It is reported two British longboat oarsmen were killed, with several others wounded.

Despite the efforts of the British sailors to turn the ship around and retreat out to Boston Harbor, the Diana was caught in the mud flats as the tide withdrew shortly before dark. Graves ordered the ship be stabilized and for a short while the British were able to continue to fight the colonists from her stationary position. The stabilization did not last long, however, as the mud in the marshes and estuaries surrounding Boston, then as now, is boggy and consuming in its effect, and the HMS Diana rolled over. Now, on her beam ends, the Diana was useless to the British as they could not keep to the deck, nor could they fire the guns. Around 10pm Graves ordered the Diana abandoned.

Sometime around midnight the revolutionaries boarded the British vessel, looted her to the core, and burned her down. The munitions taken from the Diana, including canons and swivel guns, as well as ammunition were used against the British a short time later at the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Losses for both sides were considered very light. The American records are considered precise; however there is some disagreement as to whether the British intentionally misrepresented their losses from the battle. Most historians agree no Americans lost their lives, though three were wounded at the Battle of Chelsea Creek. Two British soldiers lost their lives while several more were wounded. Gains for the rebels were high. While estimates do vary, it’s generally accepted that in addition to the aforementioned munitions looted from the Diana, the colonists also came away with about 450 sheep, 40 heads of cattle and some horses.

In The Revolutionary War Battle America Forgot: Chelsea Creek, 27-28 May 1775 (Brown, Mastone, and Maio 2013) the authors contend that this little, short lived altercation (several hours of actual battle, a day or two leading up to it and the few skirmishes in days to follow) was slighted its place in history for three very plausible reasons. First, very few accounts of the battle exist from the men themselves who were on the battle field. There are a few and they serve as the main primary resources historians have when attempting to understand the events associated with the battle. Secondly, there were few if any eye witnesses to the action given the diminishing daylight and then darkness coupled with the fact that the altercation took place out in the marsh, a hard place to see into from the periphery under even good daylight conditions. Thirdly, historian and Judge Albert Bossom considered historians’ neglect of the battle something akin to a criminal cover up. He publicly blamed Richard Frothingham especially for deliberately suppressing facts about the battle in effort to promote the heroism of his friend William Prescott at Bunker Hill.

Regardless, The Battle of Chelsea Creek was exceptionally important, as much as the battles at Lexington and Concord and at Bunker Hill. The engagement at Chelsea Creek was the first time three separate colonies’ militia men worked together towards a common goal, repelling the British, and from this point on the future colonial military engagements would include men from around the region. Prior to the Battle, colonists were successful in removing or destroying most of the livestock and other resources relied upon by the British. Also, given the young age and inexperience of the majority of colonial militia men, the Battle of Chelsea Creek afforded on-the-job-training, and provided real world warfare experience against an enemy these soldiers would face repeatedly. Munitions taken from the Diana were used shortly thereafter to fortify positions and gain victory at the Battle of Bunker Hill. The Battle of Chelsea Creek also signified the first time the American rebels went on the offensive. The organization demonstrated by the three commanding officers as well as the cooperation of the civilian soldiers themselves – fighting shoulder to shoulder with men from across three colonies with whom they had not trained and in many instances did not know – indicated they were well prepared, organized and committed to the cause only a month after Lexington and Concord. The victory at Chelsea Creek also provided a wave of confidence and a huge morale boost. Civilian soldiers, many of whom had left families and farms to join the war effort, had experienced and reveled in the destruction of a Royal Navy warship, and that epic experience for many likely inspired the confidence and gusto with which the colonists fought in all future Revolutionary engagements.

One can easily experience Minuteman National Park, the Battle Green, and Old North Bridge with a visit to Lexington and Concord. It is family friendly, well signed, and dotted with informational kiosks for those interested in a self-guided adventure. Visitors can also opt for guided-tours led by enthusiastic historians, and the area is home to frequent reenactments. Lexington and Concord wear their Revolutionary War roots with obvious pride, and because of its authenticity and emphasis on accurately telling the story of the fight for the birth of America, visitors from around the nation and the world come to Lexington and Concord.

The same is true for Bunker Hill, located in the Charlestown section of Boston. A 20 story obelisk paying tribute to the third battle of the Revolution is on many tourists’ hit lists when visiting historical sights in Boston. Bunker Hill is easy to get to, fun to visit; and, like Lexington and Concord, it’s a highly advertised and well known Revolutionary site. Oddly, the Battle of Chelsea Creek site – which is also easy to get to from Boston and surrounding areas – is not on anyone’s radar. It is all but ignored by the few who know its location, and is passed by (usually at 55 mph) by others unaware of the Battle or its significance. There is no ranger, no museum, and no parking: nothing official by way of interpretation to aid a visitor through the experience of what the Battle of Chelsea Creek would have looked like, and what its positive contributions were relative to victory in the American Revolution. There is only a lone plaque, which stands at the corner of a busy intersection of Broadway and the Revere Beach Parkway (near the parking lot for the municipal skating rink), commemorating the Battle. But if you wish, you can park at the lot by the rink, and walk out to the edge of the reedy, overgrown bank by the creek’s waters. With the right kind of eyes you can envision the battle unfolding; the heroics of the patriots, musket shots ringing out, canon fire exploding in the night, and the raging red-orange flames of the HMS Diana against the black of a midnight sky.

In The Revolutionary War Battle America Forgot: Chelsea Creek, 27-28 May 1775 (Brown, Mastone, and Maio 2013) the authors contend that this little, short lived altercation (several hours of actual battle, a day or two leading up to it and the few skirmishes in days to follow) was slighted its place in history for three very plausible reasons. First, very few accounts of the battle exist from the men themselves who were on the battle field. There are a few and they serve as the main primary resources historians have when attempting to understand the events associated with the battle. Secondly, there were few if any eye witnesses to the action given the diminishing daylight and then darkness coupled with the fact that the altercation took place out in the marsh, a hard place to see into from the periphery under even good daylight conditions. Thirdly, historian and Judge Albert Bossom considered historians’ neglect of the battle something akin to a criminal cover up. He publicly blamed Richard Frothingham especially for deliberately suppressing facts about the battle in effort to promote the heroism of his friend William Prescott at Bunker Hill.

Regardless, The Battle of Chelsea Creek was exceptionally important, as much as the battles at Lexington and Concord and at Bunker Hill. The engagement at Chelsea Creek was the first time three separate colonies’ militia men worked together towards a common goal, repelling the British, and from this point on the future colonial military engagements would include men from around the region. Prior to the Battle, colonists were successful in removing or destroying most of the livestock and other resources relied upon by the British. Also, given the young age and inexperience of the majority of colonial militia men, the Battle of Chelsea Creek afforded on-the-job-training, and provided real world warfare experience against an enemy these soldiers would face repeatedly. Munitions taken from the Diana were used shortly thereafter to fortify positions and gain victory at the Battle of Bunker Hill. The Battle of Chelsea Creek also signified the first time the American rebels went on the offensive. The organization demonstrated by the three commanding officers as well as the cooperation of the civilian soldiers themselves – fighting shoulder to shoulder with men from across three colonies with whom they had not trained and in many instances did not know – indicated they were well prepared, organized and committed to the cause only a month after Lexington and Concord. The victory at Chelsea Creek also provided a wave of confidence and a huge morale boost. Civilian soldiers, many of whom had left families and farms to join the war effort, had experienced and reveled in the destruction of a Royal Navy warship, and that epic experience for many likely inspired the confidence and gusto with which the colonists fought in all future Revolutionary engagements.

One can easily experience Minuteman National Park, the Battle Green, and Old North Bridge with a visit to Lexington and Concord. It is family friendly, well signed, and dotted with informational kiosks for those interested in a self-guided adventure. Visitors can also opt for guided-tours led by enthusiastic historians, and the area is home to frequent reenactments. Lexington and Concord wear their Revolutionary War roots with obvious pride, and because of its authenticity and emphasis on accurately telling the story of the fight for the birth of America, visitors from around the nation and the world come to Lexington and Concord.

The same is true for Bunker Hill, located in the Charlestown section of Boston. A 20 story obelisk paying tribute to the third battle of the Revolution is on many tourists’ hit lists when visiting historical sights in Boston. Bunker Hill is easy to get to, fun to visit; and, like Lexington and Concord, it’s a highly advertised and well known Revolutionary site. Oddly, the Battle of Chelsea Creek site – which is also easy to get to from Boston and surrounding areas – is not on anyone’s radar. It is all but ignored by the few who know its location, and is passed by (usually at 55 mph) by others unaware of the Battle or its significance. There is no ranger, no museum, and no parking: nothing official by way of interpretation to aid a visitor through the experience of what the Battle of Chelsea Creek would have looked like, and what its positive contributions were relative to victory in the American Revolution. There is only a lone plaque, which stands at the corner of a busy intersection of Broadway and the Revere Beach Parkway (near the parking lot for the municipal skating rink), commemorating the Battle. But if you wish, you can park at the lot by the rink, and walk out to the edge of the reedy, overgrown bank by the creek’s waters. With the right kind of eyes you can envision the battle unfolding; the heroics of the patriots, musket shots ringing out, canon fire exploding in the night, and the raging red-orange flames of the HMS Diana against the black of a midnight sky.

YE OLDE RUMNEY MARSH BURIAL GROUND

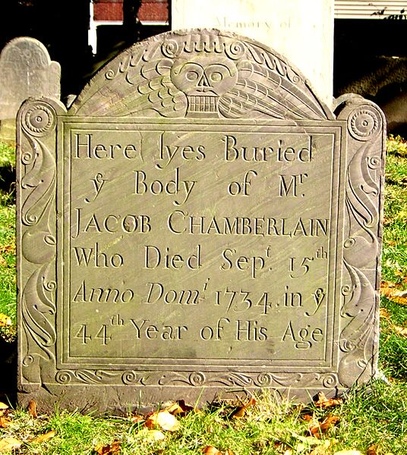

A headstone at the Rumney Marsh Burial Ground.

Photo by James Woodward.

A headstone at the Rumney Marsh Burial Ground.

Photo by James Woodward.

The Rumney Marsh Burial ground is one of the oldest burial grounds in the nation. Located not far from current day Butler Street, the burial ground is the final resting place for many of Revere’s earliest citizens. The first known burial traces back to 1693 when the wife of Captain John Smith (a different Smith, not of Pocahontas fame) was buried in a plot at the cemetery. The Captain joined his wife there some years later. While burials continued at the site from that time forward, it was not until 1748 that the land was officially willed to the town for use as a cemetery by Joshua Cheever, son of the town’s first known teacher.

Those who have visited the burial ground know that it is not large, though it is densely lined with markers and stones, many of which are broken now – eroded by age and weather, or damaged by vandals. Still, one can read the names of those interned here, notice their birth and death dates, and realize from their often short life spans that life was hard in the early days of our town, and one’s passing often came at a young age.

A monument greets the visitor to the burial ground and displays some of the names of those interred here, and provides some brief history as well. Deane Winthrop, who was the son of the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay is buried at the Old Rumney Marsh Burial Ground. Accounts of his funeral indicate it was a formal affair, attended by some of Boston’s most prominent citizens, many arriving by coach. Thomas Cheever, the town’s first teacher, who passed at age 92, is also buried here, as are his two wives. Thomas Pratt, for whom the current day Prattville neighborhood in Chelsea is named, is also buried here. He maintained a large farm in the region, and is known to have built a grist mill on the edge of Chelsea Creek where current day Slade’s Mill is located, near Route 16.

Revolutionary war heroes are also represented at the Old Rumney Marsh Burial Ground. One such figure, Samuel Sprague*, led three companies of Minute Men. Additionally, he was also present at the Battle of Chelsea Creek, fighting off the British Navy from a land position hidden in the reeds and rushes of the marshland. Parson Payson*, a Revolutionary War hero, is buried here, as is his compatriot Joseph Green*. Mr. Green’s son, Joseph Jr. is also buried at the burial ground. He is known for providing refreshments to the colonists during the Battle of Chelsea Creek.

The Old Rumney Marsh Burial Ground is the hallowed resting place for the earliest citizenry of the place which would become Revere. A visit to it provides one with a sense of history and awe, carrying the visitor back to a time when Rumney Marsh was less populated but certainly vital. While I am quite unaware of any statistics regarding its visitation, I am certain many current day citizens of Revere may be unaware of the wonderful resource they have in the Old Rumney Marsh Burial Ground. Indeed, many may be unaware of its presence at all.

Those who have visited the burial ground know that it is not large, though it is densely lined with markers and stones, many of which are broken now – eroded by age and weather, or damaged by vandals. Still, one can read the names of those interned here, notice their birth and death dates, and realize from their often short life spans that life was hard in the early days of our town, and one’s passing often came at a young age.

A monument greets the visitor to the burial ground and displays some of the names of those interred here, and provides some brief history as well. Deane Winthrop, who was the son of the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay is buried at the Old Rumney Marsh Burial Ground. Accounts of his funeral indicate it was a formal affair, attended by some of Boston’s most prominent citizens, many arriving by coach. Thomas Cheever, the town’s first teacher, who passed at age 92, is also buried here, as are his two wives. Thomas Pratt, for whom the current day Prattville neighborhood in Chelsea is named, is also buried here. He maintained a large farm in the region, and is known to have built a grist mill on the edge of Chelsea Creek where current day Slade’s Mill is located, near Route 16.

Revolutionary war heroes are also represented at the Old Rumney Marsh Burial Ground. One such figure, Samuel Sprague*, led three companies of Minute Men. Additionally, he was also present at the Battle of Chelsea Creek, fighting off the British Navy from a land position hidden in the reeds and rushes of the marshland. Parson Payson*, a Revolutionary War hero, is buried here, as is his compatriot Joseph Green*. Mr. Green’s son, Joseph Jr. is also buried at the burial ground. He is known for providing refreshments to the colonists during the Battle of Chelsea Creek.

The Old Rumney Marsh Burial Ground is the hallowed resting place for the earliest citizenry of the place which would become Revere. A visit to it provides one with a sense of history and awe, carrying the visitor back to a time when Rumney Marsh was less populated but certainly vital. While I am quite unaware of any statistics regarding its visitation, I am certain many current day citizens of Revere may be unaware of the wonderful resource they have in the Old Rumney Marsh Burial Ground. Indeed, many may be unaware of its presence at all.

REVERE BEACH: THEN & NOW

Revere Beach is the single most recognizable feature of Revere. It is a beautiful, crescent-shaped sandy beach running about three miles from Eliot Circle to the Point of Pines in Revere. Today its beautiful waters are lined with homes, condos, and eateries. It hosts the Revere Beach Sand Castle Competition each summer. In its heyday, Revere Beach was known as the “People’s Beach” – the first public beach in the nation – and it was not uncommon for nearly 100,000 people to share the sand and surf on any given summer’s day. Later, the Beach would be known as the Coney Island of New England for its famous amusements, theaters, and attractions. Ever constant, beautiful and alluring, Revere Beach now as then is the focal point of the city.

In 1834 the first of many establishments was opened along Revere Beach. The Robinson Crusoe House located at the Point of Pines and built by Solomon Hayes, was a hotel, restaurant and tavern. This two room inn was frequented by sportsmen who came for the fishing and duck hunting and by travelers who simply wanted to enjoy the peace and beauty of the shore. It continued to operate until 1857 when the Ocean House was built on the same footprint. In the ensuing years numerous restaurants, hotels and taverns were built along the thee mile stretch of beachfront.

The Narrow Gauge Railroad, an early version of the Blue Line and Commuter Rail wrapped up into one, carried passengers from Boston to Lynn with multiple stops along Revere Beach. Officially named the Boston, Revere Beach and Lynn Railroad, “Narrow Gauge” was the popular nickname and what most passengers used. In The Story of Revere Beach, George Clarke argues that the Narrow Gauge Railroad had the single most dramatic effect on promoting the growth of Revere. In 1879 the New Pavilion Hotel was built along the beach and served as a hotel as well as a Narrow Gauge railway station. The list of establishments along Revere Beach in its early years prior to the turn of the century is long and varied, but each provided service to the throngs of visitors during the warmer months of the year.

The Narrow Gauge Railroad, an early version of the Blue Line and Commuter Rail wrapped up into one, carried passengers from Boston to Lynn with multiple stops along Revere Beach. Officially named the Boston, Revere Beach and Lynn Railroad, “Narrow Gauge” was the popular nickname and what most passengers used. In The Story of Revere Beach, George Clarke argues that the Narrow Gauge Railroad had the single most dramatic effect on promoting the growth of Revere. In 1879 the New Pavilion Hotel was built along the beach and served as a hotel as well as a Narrow Gauge railway station. The list of establishments along Revere Beach in its early years prior to the turn of the century is long and varied, but each provided service to the throngs of visitors during the warmer months of the year.

In 1896 the Metropolitan Park Commission was charged with overseeing the newly established Revere Beach Reservation. They moved to hire Charles Eliot, a disciple of Frederick Law Olmstead – the well-known landscape architect and designer of such open spaces as Central Park and the “emerald necklaces” of green space and park lands surrounding the metro areas of Boston and Chicago.

Eliot designed and executed the landscape architecture we still see and enjoy today at Revere Beach. His first and foremost guiding principle is found in his statement that “we must not conceal from visitors the long sweep of the open beach, which is the finest thing about the reservation.” Shortly thereafter the Narrow Gauge Railroad tracks were moved off of the beachfront where they had paralleled the coast along Revere Beach, and was reestablished about 400 yards back where the current day Blue Line tracks stand.

In 1900 as the century was turning so too was Revere Beach, which saw more visitors drawn to its many attractions with fewer coming to hunt and fish. Three men – William Neal, Paul Bracket, and John O’Brien – came up with the idea of Carnival Week as a way to promote the beach, and attract even larger crowds. Their idea was enthusiastically received by the Narrow Gauge Railroad and by the management of various attractions along Revere Beach Boulevard, who came together to help finance the project.

Carnival Week featured a number of unusual attractions, including fireworks, band concerts, swimming and rowing contests, and a beauty contest. Also, one could witness Boynton’s Diving Horses – the white horses named King and Queenie that would amaze onlookers by diving from a platform down into the water.

In 1901 Carnival Week featured the Revere Cycle Track. The MacLean brothers built the track – 30 feet wide and in places slanting up to 45 degrees – for motorcycle racing. It was a sophisticated operation that attracted thousands of spectators who had never seen anything like it before.

Eliot designed and executed the landscape architecture we still see and enjoy today at Revere Beach. His first and foremost guiding principle is found in his statement that “we must not conceal from visitors the long sweep of the open beach, which is the finest thing about the reservation.” Shortly thereafter the Narrow Gauge Railroad tracks were moved off of the beachfront where they had paralleled the coast along Revere Beach, and was reestablished about 400 yards back where the current day Blue Line tracks stand.

In 1900 as the century was turning so too was Revere Beach, which saw more visitors drawn to its many attractions with fewer coming to hunt and fish. Three men – William Neal, Paul Bracket, and John O’Brien – came up with the idea of Carnival Week as a way to promote the beach, and attract even larger crowds. Their idea was enthusiastically received by the Narrow Gauge Railroad and by the management of various attractions along Revere Beach Boulevard, who came together to help finance the project.

Carnival Week featured a number of unusual attractions, including fireworks, band concerts, swimming and rowing contests, and a beauty contest. Also, one could witness Boynton’s Diving Horses – the white horses named King and Queenie that would amaze onlookers by diving from a platform down into the water.

In 1901 Carnival Week featured the Revere Cycle Track. The MacLean brothers built the track – 30 feet wide and in places slanting up to 45 degrees – for motorcycle racing. It was a sophisticated operation that attracted thousands of spectators who had never seen anything like it before.

Via reverebeach.com

Via reverebeach.com

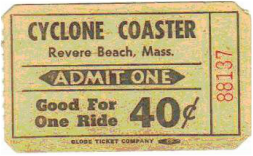

Revere Beach boasted a lot of roller coasters throughout its time as a stellar coastal entertainment destination. Some roller coasters in the early 1920s at Revere Beach were the Dragon Gorge and the Thompson Scenic Railway. Additionally, the Thunderbolt, the Jack Rabbit, and the Derby Racer were available to take the rider on a fast, scary track guaranteeing adrenaline, and for most, a fun experience. The Tickler was also a Revere Beach staple in the early years of roller coaster attractions. Around 1925 two soon-to-be-classic roller coasters came onto the scene at Revere Beach – The Lightening Roller Coaster and The Cyclone. The Lightening Roller Coaster was considered by some to be the most frightening coaster in the world. Constructed entirely of steel, and with no level track except at the entry and exit point, riders experienced steep grades, banked turns and fast speeds. Built by Harry Davis and Harry Travers, The Lightening lasted only a number of years – driven out of business by the high cost of taxes, insurance, maintenance, and the economic hit of the Great Depression.

Built a short time before the Lightening, The Cyclone operated for nearly five decades. Opened in 1925 and running until 1969, The Cyclone was a classic wooden coaster, and was the largest in the world at the time. It boasted over 3,600 feet of track, speeds of fifty miles per hour, and a one hundred foot vertical drop which took riders’ breaths away. Harry Travers also built The Cyclone. The cost was high for its day, coming in at about $125,000, but the venture quickly made its initial investment back due to the coaster’s wild popularity. In its heyday The Cyclone could handle about 1,400 riders per hour; an astonishing number attesting to the popularity of the ride and the efficiency of its attendants.

I was only two years old when The Cyclone ceased operations in 1969 after a fire had hit the network of wooden beams supporting the tracks. I never had the chance to ride the classic coaster. I do have memories though of the hulking structure standing tall and proud along the beach – however disheveled she may have been by the ravages of fire, time, weather, vandalism and abandonment. She still looked good to my 5 year-old eyes, almost seeming ride-ready, and I half expected The Cyclone to open one day, unaware as I was at my innocent age that the rides were to be over forever. Two years later, in 1974, the charred remains of The Cyclone would be demolished and removed from the Revere Beach landscape.

Built a short time before the Lightening, The Cyclone operated for nearly five decades. Opened in 1925 and running until 1969, The Cyclone was a classic wooden coaster, and was the largest in the world at the time. It boasted over 3,600 feet of track, speeds of fifty miles per hour, and a one hundred foot vertical drop which took riders’ breaths away. Harry Travers also built The Cyclone. The cost was high for its day, coming in at about $125,000, but the venture quickly made its initial investment back due to the coaster’s wild popularity. In its heyday The Cyclone could handle about 1,400 riders per hour; an astonishing number attesting to the popularity of the ride and the efficiency of its attendants.

I was only two years old when The Cyclone ceased operations in 1969 after a fire had hit the network of wooden beams supporting the tracks. I never had the chance to ride the classic coaster. I do have memories though of the hulking structure standing tall and proud along the beach – however disheveled she may have been by the ravages of fire, time, weather, vandalism and abandonment. She still looked good to my 5 year-old eyes, almost seeming ride-ready, and I half expected The Cyclone to open one day, unaware as I was at my innocent age that the rides were to be over forever. Two years later, in 1974, the charred remains of The Cyclone would be demolished and removed from the Revere Beach landscape.

A far more forgiving ride – much slower and easier to take for children of all ages – was the carousel. Revere Beach boasted its share of these iconic rides. Built in 1903 the Hippodrome was likely the most well known, and rather unique for a number of reasons. Like all carousels, it featured horses – in this case hand carved wooden horses – which were sat upon by riders who were taken around in a slow moving circle while being entertained with music. The Hippodrome featured horses which were three abreast, making it unlike the other carousels on the Beach at the time. Later the ride would be expanded, and five horses would be mounted abreast making it the only one like it in the world. I have vivid memories of riding on the Hippodrome from age 4 through about 6. In addition to the Hippodrome, Revere Beach offered the visitor a number of other carousels including The Rough Riders, The Teddy Bear Merry Go Round, and Hurley’s Hurdlers.

Also famous at Revere Beach were the many dance halls which lined the beach and nearby neighborhoods. From 1900 until the 1970s Revere Beach was known for venues dedicated to music, dancing and similar entertainment. Of all, the Ocean Pier Dancing Pavilion must have been the most inspiring. Built on a pier above the ocean waters, visitors would walk from Revere Beach Boulevard onto the boardwalk style pier over to the ballroom where big band music would ring out into the night. These days all which remains are the wooden pylons which once supported the boardwalk and pier on which the pavilion once stood. Visitors to the Eliot Circle (named for Charles Eliot) end of Revere Beach can gaze out at the last remaining evidence of the Ocean Pier Dancing Pavilion and guess to themselves how many marriage proposals were made at that venue in its day.

Other dance halls included the Frolic, where headline entertainment from Boston and New York including Guy Lombardo, Jimmy Dorsey, and Tommy Dorsey, performed amid the salt air; the Beachcroft; the Nautical Gardens; the Spanish Gables; and the Moorish Castle – each ornately decorated and designed. One cannot forget either the Wonderland Ballroom, which remained in operation until the 1980s. During the 1930s in particular dance marathons were held regularly. It was common place for dancers to rack up exceptionally large numbers of dance hours in an effort to capture the elusive cash prizes, sometimes up to a couple thousand dollars – big money during the Depression.

Also famous at Revere Beach were the many dance halls which lined the beach and nearby neighborhoods. From 1900 until the 1970s Revere Beach was known for venues dedicated to music, dancing and similar entertainment. Of all, the Ocean Pier Dancing Pavilion must have been the most inspiring. Built on a pier above the ocean waters, visitors would walk from Revere Beach Boulevard onto the boardwalk style pier over to the ballroom where big band music would ring out into the night. These days all which remains are the wooden pylons which once supported the boardwalk and pier on which the pavilion once stood. Visitors to the Eliot Circle (named for Charles Eliot) end of Revere Beach can gaze out at the last remaining evidence of the Ocean Pier Dancing Pavilion and guess to themselves how many marriage proposals were made at that venue in its day.

Other dance halls included the Frolic, where headline entertainment from Boston and New York including Guy Lombardo, Jimmy Dorsey, and Tommy Dorsey, performed amid the salt air; the Beachcroft; the Nautical Gardens; the Spanish Gables; and the Moorish Castle – each ornately decorated and designed. One cannot forget either the Wonderland Ballroom, which remained in operation until the 1980s. During the 1930s in particular dance marathons were held regularly. It was common place for dancers to rack up exceptionally large numbers of dance hours in an effort to capture the elusive cash prizes, sometimes up to a couple thousand dollars – big money during the Depression.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Wonderland Park is another gem from Revere Beach’s storied past. A concept many believe was a forerunner to today’s Disney parks, Wonderland Park attempted to transport the park goer with an entertaining, all inclusive experience. Like the contemporary Disney theme parks Wonderland featured a parade every day. It also had rides for all age levels and thrills from mild to wild. Laid out on 30 acres of land, Wonderland Park was a sprawling, first of its kind theme park in the nation. A beautiful lagoon sat as the centerpiece of Wonderland, and a thrill ride took place adjacent to and ultimately on the lagoon. Shoot the Chute allowed patrons to ride in a gondola, slide down a giant water slide at a high angle, then out onto the lagoon. Unfortunately Wonderland Park remained in business for only six years. Due to overwhelming financial troubles, Wonderland shut down in 1911. The land lay fallow for quite some time, and in 1935 was reopened as Wonderland Dog Track. While I could not have known Wonderland Park given its age, I did grow up with the dog track firmly entrenched as part of the local culture and economy. Sometime in my later thirties, about a decade ago, racing ceased at Wonderland. With its position across from a Blue Line T stop bearing its namesake, the Wonderland area is poised for its next rebirth whenever someone with the means and vision steps up to the plate with a plan the community can embrace. Likewise, Suffolk Downs, the one time premiere horse racing track where the mighty Seabiscuit once ran proud and lean, provided a lot of jobs and entertainment to the community. Only in recent years has live racing come to a stop. The track and its grand stand once hosted the Beatles in the early 60s and like the site at Wonderland is poised for rebirth. What Suffolk Downs now needs are those with vision and the financial wherewithal to realize it. Accessible via highway and the T, the Suffolk Downs site is an exceptionally valuable piece of Revere’s past, its present, and (hopefully) it's future.

Photo via visitingnewengland.com.

Photo via visitingnewengland.com.

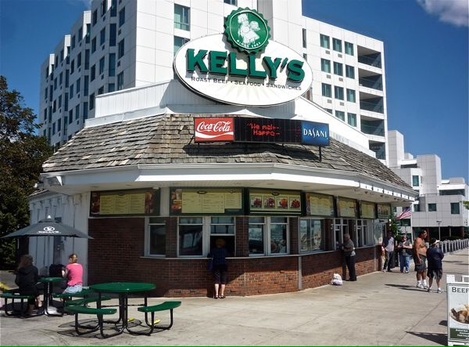

Any discussion of Revere Beach would be incomplete without mention of the world famous Kelly’s Roast Beef, which has been a staple at the beach since 1951. The restaurant’s website notes that Kelly’s was the creator of the first ever roast beef sandwich. Since that time Kelly’s has served untold numbers of their trademark sandwiches, as well as fish and chips, clams, cheeseburgers, and all the fare one would associate with a beachside establishment. Currently the family run restaurant has grown into an operation boasting five locations across the area.While all locations do quite well, some believe eating food from the original location, at the beach, sitting on the wall in the sun, makes for the perfect Kelly’s experience. Many a seagull has benefitted from me or my friends or family when a french fry or three was proffered. Multiply that by the hundreds of thousands of people who have enjoyed this classic Revere Beach fare along the wall and that’s a lot of very plump, very satisfied gulls.

THE PUBLIC LIBRARY

The first documented public library serving our area was named the Chelsea Social Library, which was established around 1825. Reverend Joseph Tuckerman* is credited with founding the library, and the prominent Carey* family is said to have donated the lion’s share of books, including many from their extensive personal collection. At that time, patrons of the library paid one dollar in exchange for the opportunity to borrow books without limit.

In 1835, ten years after the founding of the Chelsea Social Library, a new town hall was built in the part of Chelsea now known as Revere. The library moved its resources to a room in this new building, only to see it go up in flames in 1897. The library had about 5,300 titles in its holdings at the time of the fire, approximately 3,300 of which were out in circulation. In the end, the Chelsea Social Library lost roughly 2,000 books to the flames, but was reborn in a location on Broadway where it continued to loan books to the public.

After the fire, fund raising efforts to finance a new library building began in earnest. The Revere Women’s Club organized a library fair, along with other fundraising activities, eventually raising more than $3,000 towards the purchase of a lot where the library now stands. The president of the Women’s Club, Samantha Sparkhawk, then reached out to steel magnate and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie in an effort to secure enough funding to assure the library would come to fruition. Carnegie, whose philanthropy helped establish the New York City Public Library System as one of the nation’s best, was struck by the story relayed by Mrs. Sparkhawk. He endowed the town with $20,000 to erect the new library building. Money raised by the Women’s Club, combined with various other gifts and contributions, was used to purchase books and materials for each of its two rooms (one for adults and the other for children). The words, “A Gift of Andrew Carnegie” may still be read above the front doors to the Revere Public Library.

In 1835, ten years after the founding of the Chelsea Social Library, a new town hall was built in the part of Chelsea now known as Revere. The library moved its resources to a room in this new building, only to see it go up in flames in 1897. The library had about 5,300 titles in its holdings at the time of the fire, approximately 3,300 of which were out in circulation. In the end, the Chelsea Social Library lost roughly 2,000 books to the flames, but was reborn in a location on Broadway where it continued to loan books to the public.

After the fire, fund raising efforts to finance a new library building began in earnest. The Revere Women’s Club organized a library fair, along with other fundraising activities, eventually raising more than $3,000 towards the purchase of a lot where the library now stands. The president of the Women’s Club, Samantha Sparkhawk, then reached out to steel magnate and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie in an effort to secure enough funding to assure the library would come to fruition. Carnegie, whose philanthropy helped establish the New York City Public Library System as one of the nation’s best, was struck by the story relayed by Mrs. Sparkhawk. He endowed the town with $20,000 to erect the new library building. Money raised by the Women’s Club, combined with various other gifts and contributions, was used to purchase books and materials for each of its two rooms (one for adults and the other for children). The words, “A Gift of Andrew Carnegie” may still be read above the front doors to the Revere Public Library.

As a school kid I did not spend much time at the library, mainly doing my work at school or at home. However as a young college student I would often use the library as a quiet place to read, study, or write. Sometimes I would walk there, since it was a short distance from my home. Other times I would ride my bike. One time I learned a lesson about locking my bike when, after a quick visit to return some books, I came out to find my ten-speed was gone. A powerful lesson about bike security to be sure, but the incident did nothing to stop my visitation of the Revere Public Library. In addition to being a useful resource the library is also a beautiful example of Georgian Architecture. The stained glass art work, created for the library by my cousin John Misci, adds both old-world charm and modern elegance to the interior. One of the few Carnegie buildings which has not received an addition, the Revere Public Library could use a tasteful and architecturally accurate addition so that it may expand to better serve our community.

THE REVERE JOURNAL

The Revere Journal, Revere’s weekly newspaper, was born in 1881. Malden based newspaper publisher Henry Gray, the man behind that city’s weekly Mirror, became the first publisher of the Revere Journal. Printing and production took place in Malden at first. Later, in 1889 the Journal was sold to Ernest H. Pierce and he moved operations to Revere. His became the first printing press in the city. Pierce’s original location was on Beach Street, near the corner of Beach and Winthrop Ave. However, in 1901 he moved his press and full operations across from the newly built town hall, at the corner of Broadway. These days the Journal is still home-based on Broadway, though its 1901 location has changed. And like its modern day media brethren, it can be found on the World Wide Web, and large social media outlets such as Facebook.

One of the earliest, if not the first, issues of the Revere Journal featured an editorial focusing on its mission and purpose: to unify the various neighborhoods of Revere via a robust citywide newspaper serving, in a way, as a meeting place, albeit in print. Revere then, as now, was composed of many neighborhoods, and at the time of the Journal’s infancy both geographic and cultural influences sometimes interfered with citywide cohesion. The new Revere Journal sought to inform, empower, and most importantly unify the residents of Revere.

Over the collection of decades since the Revere Journal’s inception, local and occasionally national events have been reflected upon in its pages. In its first year the Journal covered the shooting of President Garfield, and issued frequent updates and bulletins on the president’s condition during the eleven weeks Garfield lived after being shot by Charles J. Guiteau. The president’s death was announced on September 19, 1881, and the tone of the Journal, reflecting that of the national mood, was somber. In Revere, the Reverend Bixby* held a memorial service in honor of the assassinated president, and locally Garfield Avenue and the Garfield School were named in his honor.

It’s been 135 years since the founding of the Revere Journal. Today, as in earlier times, the newspaper is the go to resource for local news, politics, and information.

One of the earliest, if not the first, issues of the Revere Journal featured an editorial focusing on its mission and purpose: to unify the various neighborhoods of Revere via a robust citywide newspaper serving, in a way, as a meeting place, albeit in print. Revere then, as now, was composed of many neighborhoods, and at the time of the Journal’s infancy both geographic and cultural influences sometimes interfered with citywide cohesion. The new Revere Journal sought to inform, empower, and most importantly unify the residents of Revere.

Over the collection of decades since the Revere Journal’s inception, local and occasionally national events have been reflected upon in its pages. In its first year the Journal covered the shooting of President Garfield, and issued frequent updates and bulletins on the president’s condition during the eleven weeks Garfield lived after being shot by Charles J. Guiteau. The president’s death was announced on September 19, 1881, and the tone of the Journal, reflecting that of the national mood, was somber. In Revere, the Reverend Bixby* held a memorial service in honor of the assassinated president, and locally Garfield Avenue and the Garfield School were named in his honor.

It’s been 135 years since the founding of the Revere Journal. Today, as in earlier times, the newspaper is the go to resource for local news, politics, and information.

REVERE PUBLIC SCHOOLS: THEN & NOW

In the 1830s children in Revere were schooled in a room within the town hall. By 1838 the student body had risen to 160 school aged children, and the one room school house was far too small to accommodate them all. Then as now the number of school age children is ever growing, and the current day Revere Public Schools face the same challenges presented by growth as did our forefathers and mothers in the first half of the 1800s.

Three men whose names are street names in Revere today worked together to raise money to purchase land for a dedicated school. Benjamin Shurtleff, John Wright and Zachariah Hall raised over $300, enough to purchase the land needed – a half acre lot – where the school would be built. It was to be a two story building, and plans called for a great room on the first floor where all students could be seated, in rows, facing front. With a spectrum of student ages ranging from 6 to 15, there were to be no grade levels. No first grade, second grade, etc. All students would learn together, with material differentiated when possible to match the age of the student.

Unable to secure financing from banks in Boston, the school was in jeopardy of not being built. Shurtleff paid nearly $10,000 from his own accounts and the project was completed. School children were marched from the old town hall school room to the spacious new school. There was appropriate pomp and celebration. All was wonderful, at first. However, soon the town determined that cost overruns the project had absorbed were never officially sanctioned, so the town did not take ownership of the school. It returned to Benjamin Shurtleff as his possession alone. The students were again marched out, this time without the pomp and celebration, and returned to the town hall, where teaching as usual continued. Eventually, after coming to an agreement at a town meeting, the sum of $5,000 was offered to Shurtleff for the building. Shurtleff accepted with the agreement the new school would be named for him, and it was. The Shurtleff School opened officially.

Since the opening of the Shurtleff School the city of Revere has operated up to 18 schools at any one time, depending on budgetary and population demands. Currently, the city maintains 8 buildings containing 11 total schools (some schools share the same large building or complex) despite larger enrollment and service to more students than ever before. The larger numbers are managed mainly through consolidation. In recent times the Revere Public Schools have emerged as the best urban district in the state of Massachusetts when measured by several standardized benchmarks and compared to other urban districts in the Commonwealth. Moreover, in 2014 Revere High School was honored as best urban high school in America by the National Center for Urban School Transformation.

Success does not come easy. I am a teacher in the Revere Public Schools and I am aware that for many of our students survival often takes precedence over all else, including that science fair project or haiku poem. Assisting kids in their specific needs well beyond the realm of academics is as much a part of the job – the unwritten job description if you will – as is teaching the curriculum. About 11.9% of families and 14.6% of the population of Revere live below the poverty line, including 20.4% of those under age 18 and 10.4% of those aged 65 or over. This is old data taken from the 2010 census, but I imagine the numbers are about the same in 2016, or worse. Therefore, on average one in five kids we teach lives in poverty.

What these figures don't tell us directly is what percentage of kids are living in de facto poverty, just above the line, even if it’s not poverty by definition. On the one hand we certainly ought not to lower our standards, on the other hand we always have to be highly sensitive to the fact that many of our kids come to school with exceptional needs that are far beyond the realm of academics. It’s a delicate balance to be sure, and it’s a tall order. The Revere Public Schools do it well, and it’s a shame there is no score for this on standardized testing because our already strong scores would go through the roof. There is no standardized score given for heart and soul.

Three men whose names are street names in Revere today worked together to raise money to purchase land for a dedicated school. Benjamin Shurtleff, John Wright and Zachariah Hall raised over $300, enough to purchase the land needed – a half acre lot – where the school would be built. It was to be a two story building, and plans called for a great room on the first floor where all students could be seated, in rows, facing front. With a spectrum of student ages ranging from 6 to 15, there were to be no grade levels. No first grade, second grade, etc. All students would learn together, with material differentiated when possible to match the age of the student.

Unable to secure financing from banks in Boston, the school was in jeopardy of not being built. Shurtleff paid nearly $10,000 from his own accounts and the project was completed. School children were marched from the old town hall school room to the spacious new school. There was appropriate pomp and celebration. All was wonderful, at first. However, soon the town determined that cost overruns the project had absorbed were never officially sanctioned, so the town did not take ownership of the school. It returned to Benjamin Shurtleff as his possession alone. The students were again marched out, this time without the pomp and celebration, and returned to the town hall, where teaching as usual continued. Eventually, after coming to an agreement at a town meeting, the sum of $5,000 was offered to Shurtleff for the building. Shurtleff accepted with the agreement the new school would be named for him, and it was. The Shurtleff School opened officially.

Since the opening of the Shurtleff School the city of Revere has operated up to 18 schools at any one time, depending on budgetary and population demands. Currently, the city maintains 8 buildings containing 11 total schools (some schools share the same large building or complex) despite larger enrollment and service to more students than ever before. The larger numbers are managed mainly through consolidation. In recent times the Revere Public Schools have emerged as the best urban district in the state of Massachusetts when measured by several standardized benchmarks and compared to other urban districts in the Commonwealth. Moreover, in 2014 Revere High School was honored as best urban high school in America by the National Center for Urban School Transformation.

Success does not come easy. I am a teacher in the Revere Public Schools and I am aware that for many of our students survival often takes precedence over all else, including that science fair project or haiku poem. Assisting kids in their specific needs well beyond the realm of academics is as much a part of the job – the unwritten job description if you will – as is teaching the curriculum. About 11.9% of families and 14.6% of the population of Revere live below the poverty line, including 20.4% of those under age 18 and 10.4% of those aged 65 or over. This is old data taken from the 2010 census, but I imagine the numbers are about the same in 2016, or worse. Therefore, on average one in five kids we teach lives in poverty.

What these figures don't tell us directly is what percentage of kids are living in de facto poverty, just above the line, even if it’s not poverty by definition. On the one hand we certainly ought not to lower our standards, on the other hand we always have to be highly sensitive to the fact that many of our kids come to school with exceptional needs that are far beyond the realm of academics. It’s a delicate balance to be sure, and it’s a tall order. The Revere Public Schools do it well, and it’s a shame there is no score for this on standardized testing because our already strong scores would go through the roof. There is no standardized score given for heart and soul.

Revere is a city with a long and storied history. It has exhibited an influence on my life for the last 48 years, and continues to do so today. Revere and its people have proudly enjoyed glowing times and have endured many hardships. The end of the era of Revere Beach as the entertainment capital of the region, the harsh pounding the city took during the famed Blizzard of 1978 with much flooding and terrible destruction of many homes in the area, as well as the Revere Tornado in the summer of 2014 pulling roofs off of houses and causing significant damage to the City Hall building are certainly low points in our city’s history. The strength, however, that Revere has drawn from these challenging times has pulled the city together and allowed for some of its finest moments. When the F2 tornado devastated the city’s central corridor, including a path right down Broadway, the city responded with Revere Pride, rebuilding and moving – as always – towards the future with direction and vision. This is Revere, Massachusetts. This is my hometown.

*These individuals or families have streets named after them in Revere; a tribute to their lasting impact on the town's history.

SOURCES:

- The Revolutionary War Battle America Forgot: Chelsea Creek, 27-28 May 1775 by Craig j. Brown, Victor T Mastone, and Christopher V. Maio 2013 from The New England Quarterly volume LXXXVI sept 2013

- Series of weekly articles featuring varied topics of Revere history by local historian and 35 year Revere Public School history teacher (now retired) Jeffery Pearlman which ran in the Revere Journal in the 1970s or early 80s (photocopied and on loan from the collection of Mr. Roy Colannino)

- Conversations with Jeffery Pearlman in 1998/99

- Memories of Revere Beach by local author Peter McCauley

- Revere Beach Chips: Historical Background from the Revere Journal local author Peter McCauley 1996

- Revere Beach: Images of America, Leah A. Schmidt, 2002

- Census data from Revere, MA 2010

- History of the Town of Revere, Benjamin Shurtleff 1938

- www.reverepubliclibrary.org

- www.reverebeach.com

- www.revere.org

- www.reverechmber.org

- www.kellysroastbeef.com

Header photo by T. Guzzio.

CONNECT WITH CHRISTOPHER:

Christopher Mattera, Ed.D. has been descending and photographing technical canyons on the Colorado Plateau for twenty-five years. His photography appears in Moab Canyoneering: Exploring Technical Canyons Around Moab, the newest guide book to technical canyoneering on the Colorado Plateau, recently published by Sharp End Publications. In addition he is an educator, and writer. Contact Chris at chrismattera@hotmail.com.

ADD YOUR VOICE:

ABOUT COMMENTS:

At Prodigal's Chair, thoughtful, honest interaction with our readers is important to our site's success. That's why we use Disqus as our comment / moderation system. Yes, you will need to login to leave a comment - with either your existing Facebook, Twitter, or Google+ account - or you can create your own free Disqus account. We do this for a couple of reasons: 1) to discourage trolling, and 2) to discourage spamming. Please note that Disqus will never post anything to your social network accounts unless you authorize it to do so. Finally, if you prefer you can always email comments directly to us by clicking here.