"Anthropocene" is a neologism coined by climate scientist, Paul Crutzen, who suggests that we are no longer in the Holocene - the geologic epoch that began roughly 12,000 years ago with the end of the last ice age. Rather, humans - especially since the industrial revolution - are as earthquakes, volcanoes, and meteors. We now live in the "the age of man," with new rules, forces, contingencies, powers, politics and nature. Scholars in the humanities and social sciences have seized upon this idea.

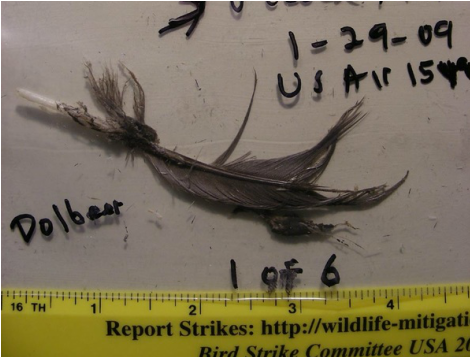

Snarge, I would argue, is a unique creature of the anthropocene. It is a word used by naturalists at the Smithsonian’s feather laboratory to refer to the avian tissue scraped from a plane’s fuselage after a bird strike. The samples are used to identify problem species that threaten jet engines. But we can recruit the word to stand in for all the animals whose lives end in a violent collision with the quintessential technologies of the anthropocene. The word snarge collects a weird assemblage: road-kill, train-strikes, bird-strikes, whale and manatee collisions.

Snarge signify a new form of killing that is unique to the anthropocene. There is no analog in the Holocene, other than stepping on ants or hitting an occasional chicken in a horse-drawn carriage.

The imperative for mass-mobility – the often unquestioned prerequisite for the industrialized human – is responsible for this new taxonomic clade of organisms that live their lives inhabiting, feeding, and traveling through novel ecosystems designed and constructed for the rapid mobility of human goods and bodies.

And so snarge is a consequence of two differentiated mobilities. An anthropocenic mobility that uses the stored energy of fossilized sunlight to hurtle heavy machines through space with terrifying celerity. And an animal mobility that must constantly adjust to the modern world.

Snarge has a long history that can provide markers for dating the anthropocene with some precision. A fitting place to start might be the death of PT Barnum’s Jumbo on September 15, 1885 after being hit by the Special Freight 151 on the Grand Trunk railway in St. Thomas, Ontario. And the Great Acceleration could be marked in 1960 with the Humane Society’s first annual 4th of July roadkill count – a bizarre anthropocenic analog to Audubon’s Christmas count. After six years, the Society disbanded the program. One organizer noted that the program “was doing no good. The conscientious few were depressed by our statistics,” (roughly a million per day), while “the indifferent majority could have cared less.”

Snarge environments are novel ecosystems that are a hybrid of materials, technologies and vegetation. They consist of 1% of overall land use in the United States. Train-beds, highway medians and right of ways, airfields, even oceanic sea-lanes and Floridian canals.

Like National Parks, National Forests and farms, snarge environments are planned, maintained, and cultivated by a heterogeneous assemblage of rambunctious gardeners to meet – largely – anthropocenic goals. Highway engineers create floral assemblages that attempt to balance the aesthetics and the safety of driving. Airfield architects create new ecosystems where planes and birds mingle in shared airspace. Florida water managers create and maintain a system of canals where manatees encounter the postwar explosion of recreational watercraft. Most of these designers would prefer a de-naturalized infrastructure without Canada geese, White-tailed deer, raccoons and manatees.

A small army of humans is concerned with snarge, but in different ways and for different reasons. All, however, are busy creating new knowledge, new sciences, and new technologies that are – again – unique to the anthropocene.

By far, the largest response by “snarge mitigators” has been to harden snarge environments – to make them uninviting and impermeable to animal mobility. These are the people who – necessarily – prioritize the mobility of human animals. Wildlife cause “accidents” that jeopardize both human life and property. The all-too-elusive goal is to create zones of exclusion. Creating these zones of separation has been the highest priority for snarge mitigators.

A second approach that is becoming increasingly popular is to accommodate animal mobility by making transportation environments permeable. Using the anthropocenic science of “road ecology,” these mitigators use fencing, culverts and overpasses to lessen the impacts of habitat fragmentation. These projects are usually found in areas where wildlife play an important role in a state’s tourism profile. Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, Arizona, California and Florida have led the way – usually close to National Parks, as with Glacier National Park’s goat underpass, or when a transportation department tangles with an endangered species, like the Florida panther. While these projects tend to be expensive, these mitigators note how the need for repairing crumbling infrastructure has led to some promising innovation between transportation engineers and wildlife biologists.

The third approach is by far the rarest and the hardest to achieve – changing the mobility behaviors of humans to accommodate non-human animals. The Florida Manatee and the North Atlantic Right Whale are the two conspicuous examples. Two activist groups that merged political activism and scientific expertise – “Save the Manatees” and the “North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium” have battled leviathan lobbies to slow down boating speeds and even move sea-lanes.

Beyond the world of wildlife hazard mitigation, snarge presents us with some uniquely anthropocenic moral quandaries. Several animal rights and welfare organizations have attempted to put snarge on their activist radars. With exceptions, most have failed because, according to one activist, road kill "is not a problem that can be easily traced to a single set of culprits. With roots that are deep and diffuse, penetrating every layer of society – political, technological, and economic – the search for a real solution requires far more than just taking on a determined opponent.”

Perhaps the best we can do is to donate money and bring our snarged critters into wildlife rehabilitation centers. Well over half of the squirrels, raccoons, birds, and turtles brought into the Roseville Rehabilitation Center, for instance, are there because of snarge encounters. Indeed, if anyone needs to restore their faith in human kindness, volunteer at one of these centers.

But is this enough? I’m not sure if there are enough overpasses or deer compost piles to assuage my unsettledness with this form of anthropocenic killing.

The sight of snarge bothers us, but not nearly enough. That fleeting twinge of regret and remorse that most of us feel when moving past a snarged deer on the highway is important for humans in the anthropocene. The feeling is a reminder of that which we all know, but choose to forget for fairly obvious reasons. There is something violently wrong with the speed of the anthropocene. Perhaps it is time to dust off our copies of Ivan Illich’s Equity and Power. In 1974, writing in the context of the ostensible energy crisis, Illich pointed to a new global speed limit beyond which the social conditions of our societies degrade –15 mph, the speed of a bicycle.

But then it would be far more difficult (at least for me) to gather at conferences. Does my quest for exculpation doom me to a life of hermitage? Must I damn you for getting in cars and planes? This hardly seems productive. Life in the anthropocene is complicated, and the problem of snarge is a bit of a hyper-object, or a wicked problem that sticks to our fingers even as we attempt to find a way out.

Snarge, I would argue, is a unique creature of the anthropocene. It is a word used by naturalists at the Smithsonian’s feather laboratory to refer to the avian tissue scraped from a plane’s fuselage after a bird strike. The samples are used to identify problem species that threaten jet engines. But we can recruit the word to stand in for all the animals whose lives end in a violent collision with the quintessential technologies of the anthropocene. The word snarge collects a weird assemblage: road-kill, train-strikes, bird-strikes, whale and manatee collisions.

Snarge signify a new form of killing that is unique to the anthropocene. There is no analog in the Holocene, other than stepping on ants or hitting an occasional chicken in a horse-drawn carriage.

The imperative for mass-mobility – the often unquestioned prerequisite for the industrialized human – is responsible for this new taxonomic clade of organisms that live their lives inhabiting, feeding, and traveling through novel ecosystems designed and constructed for the rapid mobility of human goods and bodies.

And so snarge is a consequence of two differentiated mobilities. An anthropocenic mobility that uses the stored energy of fossilized sunlight to hurtle heavy machines through space with terrifying celerity. And an animal mobility that must constantly adjust to the modern world.

Snarge has a long history that can provide markers for dating the anthropocene with some precision. A fitting place to start might be the death of PT Barnum’s Jumbo on September 15, 1885 after being hit by the Special Freight 151 on the Grand Trunk railway in St. Thomas, Ontario. And the Great Acceleration could be marked in 1960 with the Humane Society’s first annual 4th of July roadkill count – a bizarre anthropocenic analog to Audubon’s Christmas count. After six years, the Society disbanded the program. One organizer noted that the program “was doing no good. The conscientious few were depressed by our statistics,” (roughly a million per day), while “the indifferent majority could have cared less.”

Snarge environments are novel ecosystems that are a hybrid of materials, technologies and vegetation. They consist of 1% of overall land use in the United States. Train-beds, highway medians and right of ways, airfields, even oceanic sea-lanes and Floridian canals.

Like National Parks, National Forests and farms, snarge environments are planned, maintained, and cultivated by a heterogeneous assemblage of rambunctious gardeners to meet – largely – anthropocenic goals. Highway engineers create floral assemblages that attempt to balance the aesthetics and the safety of driving. Airfield architects create new ecosystems where planes and birds mingle in shared airspace. Florida water managers create and maintain a system of canals where manatees encounter the postwar explosion of recreational watercraft. Most of these designers would prefer a de-naturalized infrastructure without Canada geese, White-tailed deer, raccoons and manatees.

A small army of humans is concerned with snarge, but in different ways and for different reasons. All, however, are busy creating new knowledge, new sciences, and new technologies that are – again – unique to the anthropocene.

By far, the largest response by “snarge mitigators” has been to harden snarge environments – to make them uninviting and impermeable to animal mobility. These are the people who – necessarily – prioritize the mobility of human animals. Wildlife cause “accidents” that jeopardize both human life and property. The all-too-elusive goal is to create zones of exclusion. Creating these zones of separation has been the highest priority for snarge mitigators.

A second approach that is becoming increasingly popular is to accommodate animal mobility by making transportation environments permeable. Using the anthropocenic science of “road ecology,” these mitigators use fencing, culverts and overpasses to lessen the impacts of habitat fragmentation. These projects are usually found in areas where wildlife play an important role in a state’s tourism profile. Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, Arizona, California and Florida have led the way – usually close to National Parks, as with Glacier National Park’s goat underpass, or when a transportation department tangles with an endangered species, like the Florida panther. While these projects tend to be expensive, these mitigators note how the need for repairing crumbling infrastructure has led to some promising innovation between transportation engineers and wildlife biologists.

The third approach is by far the rarest and the hardest to achieve – changing the mobility behaviors of humans to accommodate non-human animals. The Florida Manatee and the North Atlantic Right Whale are the two conspicuous examples. Two activist groups that merged political activism and scientific expertise – “Save the Manatees” and the “North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium” have battled leviathan lobbies to slow down boating speeds and even move sea-lanes.

Beyond the world of wildlife hazard mitigation, snarge presents us with some uniquely anthropocenic moral quandaries. Several animal rights and welfare organizations have attempted to put snarge on their activist radars. With exceptions, most have failed because, according to one activist, road kill "is not a problem that can be easily traced to a single set of culprits. With roots that are deep and diffuse, penetrating every layer of society – political, technological, and economic – the search for a real solution requires far more than just taking on a determined opponent.”

Perhaps the best we can do is to donate money and bring our snarged critters into wildlife rehabilitation centers. Well over half of the squirrels, raccoons, birds, and turtles brought into the Roseville Rehabilitation Center, for instance, are there because of snarge encounters. Indeed, if anyone needs to restore their faith in human kindness, volunteer at one of these centers.

But is this enough? I’m not sure if there are enough overpasses or deer compost piles to assuage my unsettledness with this form of anthropocenic killing.

The sight of snarge bothers us, but not nearly enough. That fleeting twinge of regret and remorse that most of us feel when moving past a snarged deer on the highway is important for humans in the anthropocene. The feeling is a reminder of that which we all know, but choose to forget for fairly obvious reasons. There is something violently wrong with the speed of the anthropocene. Perhaps it is time to dust off our copies of Ivan Illich’s Equity and Power. In 1974, writing in the context of the ostensible energy crisis, Illich pointed to a new global speed limit beyond which the social conditions of our societies degrade –15 mph, the speed of a bicycle.

But then it would be far more difficult (at least for me) to gather at conferences. Does my quest for exculpation doom me to a life of hermitage? Must I damn you for getting in cars and planes? This hardly seems productive. Life in the anthropocene is complicated, and the problem of snarge is a bit of a hyper-object, or a wicked problem that sticks to our fingers even as we attempt to find a way out.

|

As always, I turn to Donna Haraway, the foremost guide to life in the anthropocene. She has recently noted that it is a mistake for us to think that we can live outside the world of killing. She invokes us, instead, to be thoughtful killers. If the snarge universe truly represents a new anthropocenic form of killing, then perhaps it is enough – at least for now – to be a bit more mindful of price that wildlife pays for our speedy ways.

And this sample of snarge – the remainder of a Canada Goose that brought down a mighty airship – is cataloged with its conspecifics and lives in a curious cabinet of its own – a storage freezer in Suitland, Maryland. But a picture of this snarge belongs in an anthropocenic cabinet to remind us that fossil-fuel based mobility has required new entanglements of species, behaviors, environments, knowledge and technologies. |

Header art by the author.

CONNECT WITH GARY:

Since graduating from the History of Science program at the University of Oklahoma in 2000, Gary Kroll has been teaching US environmental history and the history of science to undergraduates at SUNY Plattsburgh. Among other things, he is a student of twentieth century natural history and its multi-faceted role in science, popular culture and environmental politics. His previous work focused on ocean naturalists, but he has since taken up the study of novel and designer ecosystems - e.g. highway medians and airport fields - and the people who create, manage and travel through these anthropocenic ecosystems that double as transportation infrastructure. In other words, he is becoming an historian of road-kill. You can learn more about the anthropocene here, and you can reach Gary via by email at [email protected].

ADD YOUR VOICE:

ABOUT COMMENTS:

At Prodigal's Chair, thoughtful, honest interaction with our readers is important to our site's success. That's why we use Disqus as our comment / moderation system. Yes, you will need to login to leave a comment - with either your existing Facebook, Twitter, or Google+ account - or you can create your own free Disqus account. We do this for a couple of reasons: 1) to discourage trolling, and 2) to discourage spamming. Please note that Disqus will never post anything to your social network accounts unless you authorize it to do so. Finally, if you prefer you can always email comments directly to us by clicking here.