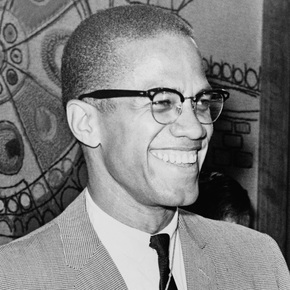

Malcolm in 1964. Photo by Ed Ford.

Malcolm in 1964. Photo by Ed Ford.

I am a 47 year-old, middle-class, white American male with a wife, a job teaching high school, a house with beach access in a little town north of Boston, and I am Malcolm X. I know there are people who will read that and think either: A) He's lost his God-damned mind, or B) He's a white, wanna-be intellectual trying to co-opt a legacy he has not earned and does not deserve.

Admittedly, I have very little in common with who Malcolm was at various points in his life. I was not the dissatisfied son of a broken home who, despite my obvious gifts, could not find support in the white world that destroyed my family. I don’t see myself in the smooth Harlem hipster who hustled his way to prison where he found God and nearly read himself blind. There is no parallel between me and the angry mouthpiece for an ideologue who eventually let Malcolm down. Nor do I identify with the wayward pilgrim who found his footing overseas, and came home more open-minded — and therefore more dangerous — to his enemies.

Maybe both “A” and “B” do describe me.

Only I feel fairly lucent most of the time. And I do strongly believe that Malcolm and I have something in common. For, underneath the large brushstrokes that comprise Malcolm’s image as the founding father of Black Nationalism, there is an accurate sketch of a religious addict.

That is the thread that ties us together.

Religious addiction is a form of process, or behavioral addiction. Process addictions are marked by an obsessive dependence on an action or activity, and are found to generate the same form of chemical dependency within the brain and body over time as other forms of addiction. Like those who are chemical dependent, process addicts engage in their compulsive behavior — like sex, gambling, eating, and spending, for example — because doing so provides them with psychological and physical gratification. And, like chemical dependency, this gratification often comes at a high cost. When the expression of any faith reaches the point where “the religious practice increasingly controls the emotions, intellect, behavior, value formation and relationships” of the practitioner, then this faith becomes what Stephen Arterburn and Jack Felton¹ call “toxic.” Family, friends, jobs and — eventually oneself -- all become lost in service to a faith structured around a myopic worldview, with little room for questions or doubt. I know that I once followed this kind of faith, and I believe that the faith Malcolm found with the Nation of Islam was toxic as well.

While much of the literature on religious addiction focuses on Christianity, the characteristics of a toxic faith and the toxically faithful work both for my time in an Evangelical congregation and Malcolm’s experience with the Nation of Islam. Religious addicts are motivated by a belief system that provides them with security and significance. Arterburn and Felton categorized this system into three groups of beliefs about authority, performance, and suffering. A religious addict assumes that, not only are we less valuable than God, “but that we are also less valuable than other people” — people who are closer to and more highly favored by God. Closely linked to this is the idea that we must work to earn God’s favor and approval. In other words, our worth as a person is contingent on our performance, as measured by those who God has put on earth to act in His stead. Lastly, rather than accept life’s inevitable setbacks with patience and grace, religious addicts seek to mitigate the presence of suffering in their lives by obsessively attempting to manipulate people and circumstances. This is because many religious addicts see their troubles as either a spiritual attack launched by the devil or some other evil force, or as a sign that one has fallen from favor with God.

Religious addicts also have lived lives that make them susceptible to physical and process addictions. Many religious addicts have dealt with instability and loss, and a good number of them have been "delivered" from physical addictions. They may have been traumatized or abused. Cheryl Zerbe Taylor² writes that, “religious addicts suffer from a deep, painful wound." For Malcolm and me, that wounding happened when we were six. For me, it was when my family imploded after moving to Las Vegas. My parents separated, which split my family in two, and resulted in the absence of my father from much of my life. For Malcolm it was the suspicious death of his father coupled with his mother’s mental collapse, which scattered him and his siblings, and robbed them of their center. Malcolm became the ward of an inherently racist social system that, by its very nature, could not have had his best interests at heart. In his autobiography³, Malcolm writes, “if ever a state social agency destroyed a family, it destroyed ours.” This destruction would leave a void – one that Malcolm would struggle to fill throughout his life, just as I would struggle with my own feelings of emptiness after my family’s collapse and my father’s retreat.

As fatherless children, and despite the best intentions and fierce efforts of our mothers, both Malcolm and I led itinerant lives, and suffered from another hallmark of potential religious addicts that Taylor identifies: low self-esteem. Malcolm found himself in and out of various foster and group homes in and around Lansing, Michigan before finally winding up in Boston with his half-sister Ella. By the time I graduated high school, I had attended nearly twenty schools as I hopscotched around the Las Vegas valley with my mother and my only remaining sibling, Michael, who was two-and-a-half years older. Malcolm and I both, it seemed, were children who desperately looked for something to hold on to; for someone through whose eyes we would be able to define ourselves.

Despite showing an aptitude for academics, the racism Malcolm encountered turned him away from school and towards petty thievery, which eventually led to a full-blown life of crime. This was famously chronicled in his autobiography, where he described his encounter with a white teacher who encouraged him to be a carpenter instead of a lawyer as “the first major turning point of my life.” While I tested well enough to merit placement in advanced classes, my academic growth was stunted by my family’s constant movement, my career as a criminal (of the smallest kind) fueled by my brother, who wanted to be a drug dealer when he grew up. Though my mother was still present in my life, she worked full time as a waitress to keep us fed and clothed, which meant that Mike and I had a dangerous amount of freedom with which to pursue our mischievous criminal enterprises. This was time spent doing things like stealing trendy toys from area department stores so that we could sell them to kids at school, and for experimenting with drugs at a dangerously young age. In short, Malcolm and I were both children with an ample amount of promise, but a feeble amount of support and guidance. Malcolm famously followed his impulses to Harlem, where he learned to hustle, pimp, and steal, while eventually winding up in prison, while I rode my brother’s coat tails to a home for troubled boys. It would be in these places where the first seeds of our religious addiction would be planted. For Malcolm, this started with his discovery of the Nation of Islam; and, more importantly, through a connection with the Nation’s leader Elijah Muhammad.

Malcolm was a broken, angry prisoner who was so averse to any form of religion fellow inmates took to calling him "Satan." This changed when members of his family joined the Nation. They told Malcolm that the NOI presented the only viable truth to the black man, and that joining would lead him to freedom. According to the NOI's teachings Malcolm’s debasement was the product of the white man's inherent evil, as manifested by its need to oppress the so-called negro. Malcolm responded to this, and soon began writing to Elijah Muhammad, who in turn became the father figure Malcolm yearned for. The two would correspond regularly while Malcolm was in prison, with Muhammad sending his young convert encouragement and even a little money here and there. In response to this positive attention, Malcolm became a steadfastly dedicated follower, spreading the NOI’s gospel to his fellow prisoners, writing letters proclaiming Muhammad’s “truth” to past associates, and famously challenging those who represented the oppressive hand of the White Devil. Malcolm’s dedication was such that, upon his release, Muhammad held Malcolm up to other Nation members as a model of devotion — of faithfulness through the worst of times. He called Malcolm “Job.”

Elijah Muhammad was in many ways the ideal toxic authority figure. Muhammad preached a message of a self worth that could only be realized by following a certain inflexible path. But he also convinced Malcolm (and rightly so) that Malcolm was more than the sum of his past actions and experiences. Muhammad encouraged Malcolm to better himself — to read, to pray, to dedicate himself to Allah and to Islam. But the religion that the NOI practiced was profoundly out of step with traditional Islamist teachings. The NOI advocated bizarre theories on race relations that were devoid of any scientific merit or support. After converting, Malcolm became a famously voracious reader, and someone who was earnest in his quest for knowledge and truth. Yet his addiction made him willing to accept even the most outrageous of Muhammad’s teachings without questions because they came wrapped in the validation and love that Malcolm yearned for.

For many years after his release, Malcolm continued his steadfast service to the NOI, becoming its greatest evangelist, organizer, and spokesperson. If it were at all possible to work one’s way into God’s favor, Malcolm seemed determined to prove it. When he joined the Nation from his prison cell in 1952, the organization had roughly one thousand members. When Malcolm was forced out twelve years later, membership had grown to over thirty thousand, largely due to his efforts. Yet despite Malcolm's dedication and blind devotion to the NOI and Elijah Muhammad, his departure from the Nation was inevitable because, more than anything else, Muhammad, Malcolm, and all other parties involved were human. Malcolm’s notoriety was not sought; it was thrust upon him as a result of his work as the NOI’s number one minister. This lead to jealousy from those who resented seeing Malcolm’s face in the papers, and caused them to work behind the scenes to weaken Malcolm's relationship with Elijah Muhammad. But it was Malcolm’s faith in Muhammad that would be shaken and destroyed, not the other way around.

Malcolm learned that Elijah Muhammad had committed adultery, fathering numerous children out of wedlock with a parade of young secretaries. Instead of censoring himself the way he had censored Malcolm’s own promiscuous brother, Reginald, years earlier (something that Malcolm fully supported by cutting Reginald from his life), Muhammad claimed that it was his right to spread his seed, the way David and other biblical figures had. He cast out those women he used his power to abuse, without supporting or acknowledging the children he fathered with them. It was at that moment when the scales would begin to lift from Malcolm’s eyes. He would reflect on this in his autobiography, stating “how, after twelve years… I became able to finally muster the nerve, and the strength, to start facing the facts, to think for myself.” But this was not an easy task, something that Spike Lee's biopic on Malcolm deftly portrays. As tensions built within the upper echelons of the Nation, Malcolm continued to work on its behalf, even as doubt began to creep into his words and actions. Eventually, it was Muhammad who severed the Nation's ties to Malcolm. During this time, Malcolm described physical symptoms that are indicative of depression. His body was wracked with numerous aches and pains. He had trouble sleeping despite the overwhelming physical and mental exhaustion he felt. In the midst of this turmoil, Malcolm repeated the figurative ablution he performed in prison: he turned away from his past and looked towards Mecca. Only this time, there was no arbiter between him and Allah. Malcolm's hadj experience would reshape his thinking as he moved forward in his faith and his work:

Admittedly, I have very little in common with who Malcolm was at various points in his life. I was not the dissatisfied son of a broken home who, despite my obvious gifts, could not find support in the white world that destroyed my family. I don’t see myself in the smooth Harlem hipster who hustled his way to prison where he found God and nearly read himself blind. There is no parallel between me and the angry mouthpiece for an ideologue who eventually let Malcolm down. Nor do I identify with the wayward pilgrim who found his footing overseas, and came home more open-minded — and therefore more dangerous — to his enemies.

Maybe both “A” and “B” do describe me.

Only I feel fairly lucent most of the time. And I do strongly believe that Malcolm and I have something in common. For, underneath the large brushstrokes that comprise Malcolm’s image as the founding father of Black Nationalism, there is an accurate sketch of a religious addict.

That is the thread that ties us together.

Religious addiction is a form of process, or behavioral addiction. Process addictions are marked by an obsessive dependence on an action or activity, and are found to generate the same form of chemical dependency within the brain and body over time as other forms of addiction. Like those who are chemical dependent, process addicts engage in their compulsive behavior — like sex, gambling, eating, and spending, for example — because doing so provides them with psychological and physical gratification. And, like chemical dependency, this gratification often comes at a high cost. When the expression of any faith reaches the point where “the religious practice increasingly controls the emotions, intellect, behavior, value formation and relationships” of the practitioner, then this faith becomes what Stephen Arterburn and Jack Felton¹ call “toxic.” Family, friends, jobs and — eventually oneself -- all become lost in service to a faith structured around a myopic worldview, with little room for questions or doubt. I know that I once followed this kind of faith, and I believe that the faith Malcolm found with the Nation of Islam was toxic as well.

While much of the literature on religious addiction focuses on Christianity, the characteristics of a toxic faith and the toxically faithful work both for my time in an Evangelical congregation and Malcolm’s experience with the Nation of Islam. Religious addicts are motivated by a belief system that provides them with security and significance. Arterburn and Felton categorized this system into three groups of beliefs about authority, performance, and suffering. A religious addict assumes that, not only are we less valuable than God, “but that we are also less valuable than other people” — people who are closer to and more highly favored by God. Closely linked to this is the idea that we must work to earn God’s favor and approval. In other words, our worth as a person is contingent on our performance, as measured by those who God has put on earth to act in His stead. Lastly, rather than accept life’s inevitable setbacks with patience and grace, religious addicts seek to mitigate the presence of suffering in their lives by obsessively attempting to manipulate people and circumstances. This is because many religious addicts see their troubles as either a spiritual attack launched by the devil or some other evil force, or as a sign that one has fallen from favor with God.

Religious addicts also have lived lives that make them susceptible to physical and process addictions. Many religious addicts have dealt with instability and loss, and a good number of them have been "delivered" from physical addictions. They may have been traumatized or abused. Cheryl Zerbe Taylor² writes that, “religious addicts suffer from a deep, painful wound." For Malcolm and me, that wounding happened when we were six. For me, it was when my family imploded after moving to Las Vegas. My parents separated, which split my family in two, and resulted in the absence of my father from much of my life. For Malcolm it was the suspicious death of his father coupled with his mother’s mental collapse, which scattered him and his siblings, and robbed them of their center. Malcolm became the ward of an inherently racist social system that, by its very nature, could not have had his best interests at heart. In his autobiography³, Malcolm writes, “if ever a state social agency destroyed a family, it destroyed ours.” This destruction would leave a void – one that Malcolm would struggle to fill throughout his life, just as I would struggle with my own feelings of emptiness after my family’s collapse and my father’s retreat.

As fatherless children, and despite the best intentions and fierce efforts of our mothers, both Malcolm and I led itinerant lives, and suffered from another hallmark of potential religious addicts that Taylor identifies: low self-esteem. Malcolm found himself in and out of various foster and group homes in and around Lansing, Michigan before finally winding up in Boston with his half-sister Ella. By the time I graduated high school, I had attended nearly twenty schools as I hopscotched around the Las Vegas valley with my mother and my only remaining sibling, Michael, who was two-and-a-half years older. Malcolm and I both, it seemed, were children who desperately looked for something to hold on to; for someone through whose eyes we would be able to define ourselves.

Despite showing an aptitude for academics, the racism Malcolm encountered turned him away from school and towards petty thievery, which eventually led to a full-blown life of crime. This was famously chronicled in his autobiography, where he described his encounter with a white teacher who encouraged him to be a carpenter instead of a lawyer as “the first major turning point of my life.” While I tested well enough to merit placement in advanced classes, my academic growth was stunted by my family’s constant movement, my career as a criminal (of the smallest kind) fueled by my brother, who wanted to be a drug dealer when he grew up. Though my mother was still present in my life, she worked full time as a waitress to keep us fed and clothed, which meant that Mike and I had a dangerous amount of freedom with which to pursue our mischievous criminal enterprises. This was time spent doing things like stealing trendy toys from area department stores so that we could sell them to kids at school, and for experimenting with drugs at a dangerously young age. In short, Malcolm and I were both children with an ample amount of promise, but a feeble amount of support and guidance. Malcolm famously followed his impulses to Harlem, where he learned to hustle, pimp, and steal, while eventually winding up in prison, while I rode my brother’s coat tails to a home for troubled boys. It would be in these places where the first seeds of our religious addiction would be planted. For Malcolm, this started with his discovery of the Nation of Islam; and, more importantly, through a connection with the Nation’s leader Elijah Muhammad.

Malcolm was a broken, angry prisoner who was so averse to any form of religion fellow inmates took to calling him "Satan." This changed when members of his family joined the Nation. They told Malcolm that the NOI presented the only viable truth to the black man, and that joining would lead him to freedom. According to the NOI's teachings Malcolm’s debasement was the product of the white man's inherent evil, as manifested by its need to oppress the so-called negro. Malcolm responded to this, and soon began writing to Elijah Muhammad, who in turn became the father figure Malcolm yearned for. The two would correspond regularly while Malcolm was in prison, with Muhammad sending his young convert encouragement and even a little money here and there. In response to this positive attention, Malcolm became a steadfastly dedicated follower, spreading the NOI’s gospel to his fellow prisoners, writing letters proclaiming Muhammad’s “truth” to past associates, and famously challenging those who represented the oppressive hand of the White Devil. Malcolm’s dedication was such that, upon his release, Muhammad held Malcolm up to other Nation members as a model of devotion — of faithfulness through the worst of times. He called Malcolm “Job.”

Elijah Muhammad was in many ways the ideal toxic authority figure. Muhammad preached a message of a self worth that could only be realized by following a certain inflexible path. But he also convinced Malcolm (and rightly so) that Malcolm was more than the sum of his past actions and experiences. Muhammad encouraged Malcolm to better himself — to read, to pray, to dedicate himself to Allah and to Islam. But the religion that the NOI practiced was profoundly out of step with traditional Islamist teachings. The NOI advocated bizarre theories on race relations that were devoid of any scientific merit or support. After converting, Malcolm became a famously voracious reader, and someone who was earnest in his quest for knowledge and truth. Yet his addiction made him willing to accept even the most outrageous of Muhammad’s teachings without questions because they came wrapped in the validation and love that Malcolm yearned for.

For many years after his release, Malcolm continued his steadfast service to the NOI, becoming its greatest evangelist, organizer, and spokesperson. If it were at all possible to work one’s way into God’s favor, Malcolm seemed determined to prove it. When he joined the Nation from his prison cell in 1952, the organization had roughly one thousand members. When Malcolm was forced out twelve years later, membership had grown to over thirty thousand, largely due to his efforts. Yet despite Malcolm's dedication and blind devotion to the NOI and Elijah Muhammad, his departure from the Nation was inevitable because, more than anything else, Muhammad, Malcolm, and all other parties involved were human. Malcolm’s notoriety was not sought; it was thrust upon him as a result of his work as the NOI’s number one minister. This lead to jealousy from those who resented seeing Malcolm’s face in the papers, and caused them to work behind the scenes to weaken Malcolm's relationship with Elijah Muhammad. But it was Malcolm’s faith in Muhammad that would be shaken and destroyed, not the other way around.

Malcolm learned that Elijah Muhammad had committed adultery, fathering numerous children out of wedlock with a parade of young secretaries. Instead of censoring himself the way he had censored Malcolm’s own promiscuous brother, Reginald, years earlier (something that Malcolm fully supported by cutting Reginald from his life), Muhammad claimed that it was his right to spread his seed, the way David and other biblical figures had. He cast out those women he used his power to abuse, without supporting or acknowledging the children he fathered with them. It was at that moment when the scales would begin to lift from Malcolm’s eyes. He would reflect on this in his autobiography, stating “how, after twelve years… I became able to finally muster the nerve, and the strength, to start facing the facts, to think for myself.” But this was not an easy task, something that Spike Lee's biopic on Malcolm deftly portrays. As tensions built within the upper echelons of the Nation, Malcolm continued to work on its behalf, even as doubt began to creep into his words and actions. Eventually, it was Muhammad who severed the Nation's ties to Malcolm. During this time, Malcolm described physical symptoms that are indicative of depression. His body was wracked with numerous aches and pains. He had trouble sleeping despite the overwhelming physical and mental exhaustion he felt. In the midst of this turmoil, Malcolm repeated the figurative ablution he performed in prison: he turned away from his past and looked towards Mecca. Only this time, there was no arbiter between him and Allah. Malcolm's hadj experience would reshape his thinking as he moved forward in his faith and his work:

|

Never have I witnessed such sincere hospitality and the overwhelming spirit of true brotherhood as is practiced by people of all colors and races here in this Ancient Holy Land, the home of Abraham, Muhammad, and all the other prophets of the Holy Scriptures. For this past week, I have been utterly speechless and spellbound by the graciousness I see displayed all around me by people of all colors.

|

It’s unclear whether Malcolm was ever able to fully free himself of his need to work his way into God’s favor, though his limited, yet growing acceptance of other people and points of view indicates that he was heading in that direction. Upon his return, Malcolm cast off the NOI’s brand of pseudo-Islam and turned away from its blind dogmatism in favor of a more traditional view of the faith. While Malcolm may have never had the chance to make peace with his country, or with the NOI, it seems his journey to Mecca allowed him to take steps towards making peace with his place in the world, and with God.

My path to religious addiction followed a similar dynamic. My Elijah Muhammad was a man named Jose Boveda. To be clear, I believe that Jose was (and still is) a good man, with good intentions who happened to have a slanted and unhealthy view of faith. I never knew Jose to be morally corrupt, and to say that he is my Elijah Muhammad isn’t to equate him with a man who espoused outrageous pseudo-scientific views on race, or who lived duplicitously. It simply means that Boveda became for me what Muhammad was for Malcolm: a father figure who helped me feel validated, and who showed me my self-worth, but whose love was predicated on my loyalty to his brand of Christianity. In fairness, this is a role I cast for Jose, one that he stepped into not because he was looking to abuse or manipulate me, but because he felt it was the right thing to do. Nevertheless, the relationship was, I believe, ultimately abusive and — to me — addictive.

Jose Boveda and his wife Toni ran the Mizpah Children’s Program in Las Vegas, Nevada. He was a former outlaw biker, drug dealer, and addict who got caught up in the Jesus People movement of the early 1970s. In his story, I also see hallmarks of religious addiction. Jose came from Cuba, where he lost his father during Castro’s revolution. When he found God, he threw himself whole-heartedly into church. He "witnessed" to the friends he had before he was "saved," become a lay-minister of sorts, and started a Christian rock band before finally deciding to open a home to rescue troubled young men from the road he once traveled. His brand of evangelical Christianity wore “non-denominational” on its sleeve like a badge of honor that indicated to all that it was Jesus who was in charge, not some distant body in the Baptist South. Looking back, it was very “punk” — a DIY movement free from rules and constraints, but also open to bizarre interpretations of doctrine and dogma, with little to no checks or balances. Jose believed in the toxic idea that one must work one’s way to heaven, something that motivated his actions, as well as his interactions with others.

My brother, Mike was sent to Mizpah after he and a friend robbed a house. While I was never formally a part of the Mizpah program, Jose and the staff weren’t averse to having me around, and I quickly grew attached to it because being there was fun. Jose, Toni, and the counselors at Mizpah filled my weekends with trips to California, to the mountains, the movies, and — yes — to church. The program provided everyone — even weekenders like me — with some greatly needed structure. I was expected to do chores when I was there. Jose taught us martial arts; and, most importantly for me, he spent time just being with us. I remember feeling special because he let me help him work on the cars he made extra money fixing. Jose listened to me without judgement. While Jose fancied himself a preacher, often giving guest sermons at some of the churches we attended, he never preached to me personally. He never once told me to repent, even though I’d hear him say it from the pulpit many times. In essence, Jose led me to religion based on how he practiced it. He shared his time, his food, his home with lost boys – some of whom had serious problems. So, from the age of ten up until I turned eighteen, my life revolved around Jose, Mizpah, and the church. It became my home; the people there, my family.

And it was awesome. The best memories of my childhood, I owe to Jose, and his willingness to take a bunch of troubled kids to places like Disneyland. My love of the ocean stems from the time he took us to Laguna Beach, where I was inked by an octopus as I waded near the shore. One summer, he took us to Colorado for three weeks worth of camping at a donor’s ranch; our time filled with ghost stories and campfires, and horseback riding. Being a part of this world made those parts of my life outside of it better, too. Jose encouraged me to do well in school. When I began to gain some recognition in school because of my artwork, Jose was there to offer encouragement and support, going so far as to hang some of my pieces in his own home.

As time went on, and my involvement in the program grew, I became an unofficial "junior counselor." This was because I knew the ropes of the program, and also because I began to take the church side of things more seriously. It was one thing to be a good kid, but being a “young man of God” was something altogether better, coming with more recognition and prestige. It was an easy call to make, especially since the brand of Christianity Jose was preaching rested so heavily on the idea of a loving God who would be a father to a fatherless kid like me, something that Jose's actions towards me seemed to bear out. By the time I was fifteen, I began to attend church heavily, at least two to three times a week. It didn't matter to me that some of the people I went to church with thought that rock music (even Christian rock) was satanic, or that others felt that when their car broke down it was because it was possessed by a demon. It didn't matter that people around me would often speak in tongues; saying things like "oh, shallabakanda!" before running up and down the aisle or falling out on the floor. Nor did it matter when my right leg, which was two-and-a-half inches shorter than my left, resulting in a noticeably strange hitch in my step, refused to grow no matter how many times I asked God to fix it. I was willing to heartily accept these things as normal because of the way being a part of the Mizpah circle made me feel.

When I was sixteen, things slowly began to change. It used to be that Jose wanted to grow the Mizpah program so that it included a home for girls, and eventually a school. But as time moved on he became more and more interested in starting a different ministry, namely a church of his own. There were many factors which, I believe, steered Jose in this direction. First, the state decided that Mizpah House needed more oversight. I’m not sure why this was, as the program had the highest success rate in the state when measured by recidivism, and there is no incident that stands out as triggering this increased scrutiny, something I think I would have been aware of given my closeness to Jose. Additionally, the program’s religious bent was no secret; the parents who sent their kids to Mizpah did so knowing that religion was part of the program, so that could not have been the issue.

Nevertheless, the state demanded that Mizpah become more regimented, more institutionalized in order to survive. These changes sucked the joy out of the place, stripping away the family feeling that existed. There could be no unsupervised walks to 7-Eleven for Slurpees and a bag of Doritos; little things that kids from stable homes took for granted, and instead of surrogate parents, the councilors at Mizpah were forced to serve as jailers. Next, Jose and Toni, who were childless when I first met them, soon had two young sons of their own (Jose had an older son from a previous marriage, who lived with his mother). Running Mizpah was a 24/7 job that offered little pay or future financial security. I think the Bovedas wanted more for their sons than food bank meals augmented by government cheese. Lastly, people came into Jose’s sphere of influence and encouraged him to preach more regularly. They started using words like “prophet.” The Bovedas soon co-founded a church with two other couples. This endeavor would fall apart when one of the lead pastors had an affair with an Elvis impersonator (true story, and only in Vegas…). But for Jose the die was cast, and he would start his own church, called “My Father’s House,” in the Mizpah living room.

At first, my brother and I went willingly in this new direction. Prior to MFH’s founding, Jose had us attend numerous churches throughout the Vegas Valley, never settling in one spot due to what must’ve been theological differences. Now we had roles in creating a stable church home. Mike, despite being only nineteen, and with no formal training, became a youth minister at the church, and I helped design its logo. When MFH formally acquired space in a storefront near downtown Las Vegas, I designed and installed the signage since I worked at a sign shop after school. We were, in a way, the young princes of the congregation, having been a part of Jose’s ministry for roughly seven years. I even “preached” from time to time, though my tendency was more towards chatting rather than to throwing on the evangelical trappings and cadences that I saw others often wear.

But as the church slowly grew, the demands it started placing on me began conflicting with the person Mizpah had helped make. I was entering the middle of my first year of college, which Jose supported and helped me pay for, when he asked me to scale back my studies in order to help run a furniture business he was starting. Jose was always looking for ways to generate income beyond what the state provided for his work at Mizpah, having started a print shop a few months prior. This time, he would be acquiring and selling used furniture remaindered from area hotels and casinos. Jose's sudden about-face with regards to my education was confusing. I didn't know where it was coming from until a relative newcomer to the church, one who quickly ingratiated himself to Jose with flattering “prophecies” about Jose’s leadership during “the Last Days,” stood before the congregants and passive-aggressively chastised those who weren’t willing to put the church first. His gaze fall squarely on me, and it stayed there until the end of his speech. Despite my confusion and discomfort, I probably would have said yes to Jose’s proposal had it not been for something else that made saying no necessary.

Maybe it was because I was older, but giving my time in service to MFH started to get burdensome. It came attached with strings that either never existed before or that I simply hadn’t recognized. Then my brother fell in love and became engaged to a girl whose parents were ministers who had fallen out with Jose and Toni. I still don’t know the full story of what led to this schism; I only know that Toni claimed to have had a “word” from the Lord stating that Mike’s impending marriage was unholy and doomed to fail. I became caught between my brother on one side, and my father figure on the other. I tried to find a middle road. I left My Father’s House, and began attending another church I had hoped would be similar. I thought I could support my brother and maintain my ties to Jose and other members of the church, including people whom I had known for almost half of my life, by keeping the faith in another location. This didn't work out. Once I stopped attending My Father's House, Jose and the others stopped communicating with me. Eventually I showed up at My Father’s House after a midweek service, looking to hang out and catch up, but I was turned away. "Hanging out with you," I was told, "just wouldn't feel right. It would be too strange." Apparently, if I wasn’t their kind of Christian, then I wasn’t a Christian at all.

I tried to mitigate Jose's role in my life by casting it as part of my journey towards a larger truth. I felt that if I could just find the right church, then I could ease the doubts about my own self-worth that were starting to nag at me as a result of Jose's absence. But I couldn't find another group of Christians who would see my obvious worth, and place me in the esteemed position I was used to. My loneliness was compounded by the fact that my brother and his new wife would soon move to New Mexico. Rudderless, I redoubled my efforts in school, which in a way became my trip to Mecca. I learned new things about the world, made friends with new people, and started to recast myself as a young intellectual who was “spiritual, but not religious.” I met someone, a graduate student, seven years my senior. We fell in love and quickly married; Jose, and all the people I had always felt would be a part of my wedding day, were strangely absent from our small ceremony.

Then I fell into a deep, debilitating depression.

Despite my numerous attempts to redefine just who exactly “Tom Guzzio” was — joining another church, throwing myself into school, and getting married (for crying out loud!), I could never recapture that same feeling of love that I felt before. I didn't know it then, but I was still going through the motions of my religious addiction. I was still performing, only now, in the absence of Jose’s approval, I sought a different standard by which to judge my work and earn God’s validation. And, I still measured God’s love for me by the presence or absence of adversity in my life — something that made even small problems beyond the scope of my ability to fix or control a measure of my worth. So while I continued to prove myself a more than capable student, finding confidence in my ability to write and to think for myself, I couldn't stop feeling that I was a fraud. I was genuinely afraid that the only true way back to happiness was to leave my wife, my education — everything — and return to My Father’s House.

Two things happened that finally began to shift my thinking about God. I stumbled across a book on religious addiction while browsing through the psychology section at a local bookstore, and I was assigned The Autobiography of Malcolm X for a class I was taking on the Black Arts Movement of the late 60s and early 70s.

It’s odd that I don’t remember the title or the author of the book on religious addiction. I only remember that it was green and black, maybe had a picture of a priest on the back cover, and that I read the whole thin volume while sitting on the floor of the store. It helped me see that my relationship with Jose, the church, and with God as I understood Him, were all unhealthy, despite how good I felt in the midst of it all, and of how bad I felt after I left it behind. It didn’t completely silence those nagging voices, but it definitely turned their volume down.

The book on religious addiction also helped me see Malcolm outside of the context of the course I was taking. True, Malcolm had a profound impact on African American culture, so much so that he even made the term “African American” possible. His influence on Black artists was clear to me, but as I read Malcolm's story, I also began to see structural similarities between his relationship with Elijah Muhammad, and my relationship with Jose, between his walk and my own. Malcolm talked of having a depth of faith in Mr. Muhammad that led him to “totally and absolutely” reject his own intelligence – something that I had nearly done, and was in danger of still doing if I turned back to the church. He talked of the hurt and shame that came with discovering that the person he held in such high esteem was, like him, simply human.

And he wrote of “the boy Icarus. Do you remember the story?”

He was the boy who defied gravity.

My path to religious addiction followed a similar dynamic. My Elijah Muhammad was a man named Jose Boveda. To be clear, I believe that Jose was (and still is) a good man, with good intentions who happened to have a slanted and unhealthy view of faith. I never knew Jose to be morally corrupt, and to say that he is my Elijah Muhammad isn’t to equate him with a man who espoused outrageous pseudo-scientific views on race, or who lived duplicitously. It simply means that Boveda became for me what Muhammad was for Malcolm: a father figure who helped me feel validated, and who showed me my self-worth, but whose love was predicated on my loyalty to his brand of Christianity. In fairness, this is a role I cast for Jose, one that he stepped into not because he was looking to abuse or manipulate me, but because he felt it was the right thing to do. Nevertheless, the relationship was, I believe, ultimately abusive and — to me — addictive.

Jose Boveda and his wife Toni ran the Mizpah Children’s Program in Las Vegas, Nevada. He was a former outlaw biker, drug dealer, and addict who got caught up in the Jesus People movement of the early 1970s. In his story, I also see hallmarks of religious addiction. Jose came from Cuba, where he lost his father during Castro’s revolution. When he found God, he threw himself whole-heartedly into church. He "witnessed" to the friends he had before he was "saved," become a lay-minister of sorts, and started a Christian rock band before finally deciding to open a home to rescue troubled young men from the road he once traveled. His brand of evangelical Christianity wore “non-denominational” on its sleeve like a badge of honor that indicated to all that it was Jesus who was in charge, not some distant body in the Baptist South. Looking back, it was very “punk” — a DIY movement free from rules and constraints, but also open to bizarre interpretations of doctrine and dogma, with little to no checks or balances. Jose believed in the toxic idea that one must work one’s way to heaven, something that motivated his actions, as well as his interactions with others.

My brother, Mike was sent to Mizpah after he and a friend robbed a house. While I was never formally a part of the Mizpah program, Jose and the staff weren’t averse to having me around, and I quickly grew attached to it because being there was fun. Jose, Toni, and the counselors at Mizpah filled my weekends with trips to California, to the mountains, the movies, and — yes — to church. The program provided everyone — even weekenders like me — with some greatly needed structure. I was expected to do chores when I was there. Jose taught us martial arts; and, most importantly for me, he spent time just being with us. I remember feeling special because he let me help him work on the cars he made extra money fixing. Jose listened to me without judgement. While Jose fancied himself a preacher, often giving guest sermons at some of the churches we attended, he never preached to me personally. He never once told me to repent, even though I’d hear him say it from the pulpit many times. In essence, Jose led me to religion based on how he practiced it. He shared his time, his food, his home with lost boys – some of whom had serious problems. So, from the age of ten up until I turned eighteen, my life revolved around Jose, Mizpah, and the church. It became my home; the people there, my family.

And it was awesome. The best memories of my childhood, I owe to Jose, and his willingness to take a bunch of troubled kids to places like Disneyland. My love of the ocean stems from the time he took us to Laguna Beach, where I was inked by an octopus as I waded near the shore. One summer, he took us to Colorado for three weeks worth of camping at a donor’s ranch; our time filled with ghost stories and campfires, and horseback riding. Being a part of this world made those parts of my life outside of it better, too. Jose encouraged me to do well in school. When I began to gain some recognition in school because of my artwork, Jose was there to offer encouragement and support, going so far as to hang some of my pieces in his own home.

As time went on, and my involvement in the program grew, I became an unofficial "junior counselor." This was because I knew the ropes of the program, and also because I began to take the church side of things more seriously. It was one thing to be a good kid, but being a “young man of God” was something altogether better, coming with more recognition and prestige. It was an easy call to make, especially since the brand of Christianity Jose was preaching rested so heavily on the idea of a loving God who would be a father to a fatherless kid like me, something that Jose's actions towards me seemed to bear out. By the time I was fifteen, I began to attend church heavily, at least two to three times a week. It didn't matter to me that some of the people I went to church with thought that rock music (even Christian rock) was satanic, or that others felt that when their car broke down it was because it was possessed by a demon. It didn't matter that people around me would often speak in tongues; saying things like "oh, shallabakanda!" before running up and down the aisle or falling out on the floor. Nor did it matter when my right leg, which was two-and-a-half inches shorter than my left, resulting in a noticeably strange hitch in my step, refused to grow no matter how many times I asked God to fix it. I was willing to heartily accept these things as normal because of the way being a part of the Mizpah circle made me feel.

When I was sixteen, things slowly began to change. It used to be that Jose wanted to grow the Mizpah program so that it included a home for girls, and eventually a school. But as time moved on he became more and more interested in starting a different ministry, namely a church of his own. There were many factors which, I believe, steered Jose in this direction. First, the state decided that Mizpah House needed more oversight. I’m not sure why this was, as the program had the highest success rate in the state when measured by recidivism, and there is no incident that stands out as triggering this increased scrutiny, something I think I would have been aware of given my closeness to Jose. Additionally, the program’s religious bent was no secret; the parents who sent their kids to Mizpah did so knowing that religion was part of the program, so that could not have been the issue.

Nevertheless, the state demanded that Mizpah become more regimented, more institutionalized in order to survive. These changes sucked the joy out of the place, stripping away the family feeling that existed. There could be no unsupervised walks to 7-Eleven for Slurpees and a bag of Doritos; little things that kids from stable homes took for granted, and instead of surrogate parents, the councilors at Mizpah were forced to serve as jailers. Next, Jose and Toni, who were childless when I first met them, soon had two young sons of their own (Jose had an older son from a previous marriage, who lived with his mother). Running Mizpah was a 24/7 job that offered little pay or future financial security. I think the Bovedas wanted more for their sons than food bank meals augmented by government cheese. Lastly, people came into Jose’s sphere of influence and encouraged him to preach more regularly. They started using words like “prophet.” The Bovedas soon co-founded a church with two other couples. This endeavor would fall apart when one of the lead pastors had an affair with an Elvis impersonator (true story, and only in Vegas…). But for Jose the die was cast, and he would start his own church, called “My Father’s House,” in the Mizpah living room.

At first, my brother and I went willingly in this new direction. Prior to MFH’s founding, Jose had us attend numerous churches throughout the Vegas Valley, never settling in one spot due to what must’ve been theological differences. Now we had roles in creating a stable church home. Mike, despite being only nineteen, and with no formal training, became a youth minister at the church, and I helped design its logo. When MFH formally acquired space in a storefront near downtown Las Vegas, I designed and installed the signage since I worked at a sign shop after school. We were, in a way, the young princes of the congregation, having been a part of Jose’s ministry for roughly seven years. I even “preached” from time to time, though my tendency was more towards chatting rather than to throwing on the evangelical trappings and cadences that I saw others often wear.

But as the church slowly grew, the demands it started placing on me began conflicting with the person Mizpah had helped make. I was entering the middle of my first year of college, which Jose supported and helped me pay for, when he asked me to scale back my studies in order to help run a furniture business he was starting. Jose was always looking for ways to generate income beyond what the state provided for his work at Mizpah, having started a print shop a few months prior. This time, he would be acquiring and selling used furniture remaindered from area hotels and casinos. Jose's sudden about-face with regards to my education was confusing. I didn't know where it was coming from until a relative newcomer to the church, one who quickly ingratiated himself to Jose with flattering “prophecies” about Jose’s leadership during “the Last Days,” stood before the congregants and passive-aggressively chastised those who weren’t willing to put the church first. His gaze fall squarely on me, and it stayed there until the end of his speech. Despite my confusion and discomfort, I probably would have said yes to Jose’s proposal had it not been for something else that made saying no necessary.

Maybe it was because I was older, but giving my time in service to MFH started to get burdensome. It came attached with strings that either never existed before or that I simply hadn’t recognized. Then my brother fell in love and became engaged to a girl whose parents were ministers who had fallen out with Jose and Toni. I still don’t know the full story of what led to this schism; I only know that Toni claimed to have had a “word” from the Lord stating that Mike’s impending marriage was unholy and doomed to fail. I became caught between my brother on one side, and my father figure on the other. I tried to find a middle road. I left My Father’s House, and began attending another church I had hoped would be similar. I thought I could support my brother and maintain my ties to Jose and other members of the church, including people whom I had known for almost half of my life, by keeping the faith in another location. This didn't work out. Once I stopped attending My Father's House, Jose and the others stopped communicating with me. Eventually I showed up at My Father’s House after a midweek service, looking to hang out and catch up, but I was turned away. "Hanging out with you," I was told, "just wouldn't feel right. It would be too strange." Apparently, if I wasn’t their kind of Christian, then I wasn’t a Christian at all.

I tried to mitigate Jose's role in my life by casting it as part of my journey towards a larger truth. I felt that if I could just find the right church, then I could ease the doubts about my own self-worth that were starting to nag at me as a result of Jose's absence. But I couldn't find another group of Christians who would see my obvious worth, and place me in the esteemed position I was used to. My loneliness was compounded by the fact that my brother and his new wife would soon move to New Mexico. Rudderless, I redoubled my efforts in school, which in a way became my trip to Mecca. I learned new things about the world, made friends with new people, and started to recast myself as a young intellectual who was “spiritual, but not religious.” I met someone, a graduate student, seven years my senior. We fell in love and quickly married; Jose, and all the people I had always felt would be a part of my wedding day, were strangely absent from our small ceremony.

Then I fell into a deep, debilitating depression.

Despite my numerous attempts to redefine just who exactly “Tom Guzzio” was — joining another church, throwing myself into school, and getting married (for crying out loud!), I could never recapture that same feeling of love that I felt before. I didn't know it then, but I was still going through the motions of my religious addiction. I was still performing, only now, in the absence of Jose’s approval, I sought a different standard by which to judge my work and earn God’s validation. And, I still measured God’s love for me by the presence or absence of adversity in my life — something that made even small problems beyond the scope of my ability to fix or control a measure of my worth. So while I continued to prove myself a more than capable student, finding confidence in my ability to write and to think for myself, I couldn't stop feeling that I was a fraud. I was genuinely afraid that the only true way back to happiness was to leave my wife, my education — everything — and return to My Father’s House.

Two things happened that finally began to shift my thinking about God. I stumbled across a book on religious addiction while browsing through the psychology section at a local bookstore, and I was assigned The Autobiography of Malcolm X for a class I was taking on the Black Arts Movement of the late 60s and early 70s.

It’s odd that I don’t remember the title or the author of the book on religious addiction. I only remember that it was green and black, maybe had a picture of a priest on the back cover, and that I read the whole thin volume while sitting on the floor of the store. It helped me see that my relationship with Jose, the church, and with God as I understood Him, were all unhealthy, despite how good I felt in the midst of it all, and of how bad I felt after I left it behind. It didn’t completely silence those nagging voices, but it definitely turned their volume down.

The book on religious addiction also helped me see Malcolm outside of the context of the course I was taking. True, Malcolm had a profound impact on African American culture, so much so that he even made the term “African American” possible. His influence on Black artists was clear to me, but as I read Malcolm's story, I also began to see structural similarities between his relationship with Elijah Muhammad, and my relationship with Jose, between his walk and my own. Malcolm talked of having a depth of faith in Mr. Muhammad that led him to “totally and absolutely” reject his own intelligence – something that I had nearly done, and was in danger of still doing if I turned back to the church. He talked of the hurt and shame that came with discovering that the person he held in such high esteem was, like him, simply human.

And he wrote of “the boy Icarus. Do you remember the story?”

He was the boy who defied gravity.

"The Flight of Icarus" by Jacob Peter Gowy

"The Flight of Icarus" by Jacob Peter Gowy

Icarus wore a pair of wings his father had made for him, wings made out of feathers and wax, and he flew free of the prison he and his father were kept in. But Icarus ignored his father’s warnings. Caught up in the glory of flight, Icarus flew too close to the sun, which melted his wings, and allowed gravity to drag him back to earth and certain death.

Upon returning to Boston to speak at Harvard, Malcolm drew a comparison between himself and Daedalus’ doomed son. As he paused to reflect just how far he had come due to his faith, how Islam “had enabled me to lift myself up from the muck and mire of this rotting world,” Malcolm “silently vowed to Allah that I never would forget that any wings I wore had been put on by the religion of Islam.” In doing so, Malcolm seemed to be saying that he would never lose sight of his proximity to the sun, that he would never feel himself to be greater than the words of his father.

But Malcolm’s confusion about who his “father” was – as represented by his toxic belief in Elijah Muhammad as the ultimate arbiter of his relationship with Allah – would be revealed later in The Autobiography as he commented on the notoriety he had attained as a NOI spokesman. Malcolm states that his international prominence was the sole result of “the wings Mr. Muhammad had put on me” (emphasis mine). In saying this, Malcolm let it slip that he too was wearing wings that were not made by God, or Allah, but by a small man from Georgia.

And yet Malcolm's profoundly impactful life belonged only to him.

This understanding came to me as finished the last few pages of his book, which I had been assigned to read for a class designed to reveal the breadth and width of Malcolm's influence. This gave me, a White-Devil, something that by the end of his life I think Malcolm intended for everyone to have: true freedom.

It would take many years to fully purge my system of the toxicity I experienced as a result of my experiences with Jose and My Father’s House. I would have to come to terms with my family’s implosion, and my father’s exodus. I would have to sift through the pain of how my relationship with Jose ended to reconnect with the good things that he taught me, things I hold onto even now. I would have to have my own child, and I’d need to learn how to be the kind of father she deserved after my marriage also ended in divorce.

I would learn that we are meant to fly too close to the sun, so long as we're wearing our own wings.

Upon returning to Boston to speak at Harvard, Malcolm drew a comparison between himself and Daedalus’ doomed son. As he paused to reflect just how far he had come due to his faith, how Islam “had enabled me to lift myself up from the muck and mire of this rotting world,” Malcolm “silently vowed to Allah that I never would forget that any wings I wore had been put on by the religion of Islam.” In doing so, Malcolm seemed to be saying that he would never lose sight of his proximity to the sun, that he would never feel himself to be greater than the words of his father.

But Malcolm’s confusion about who his “father” was – as represented by his toxic belief in Elijah Muhammad as the ultimate arbiter of his relationship with Allah – would be revealed later in The Autobiography as he commented on the notoriety he had attained as a NOI spokesman. Malcolm states that his international prominence was the sole result of “the wings Mr. Muhammad had put on me” (emphasis mine). In saying this, Malcolm let it slip that he too was wearing wings that were not made by God, or Allah, but by a small man from Georgia.

And yet Malcolm's profoundly impactful life belonged only to him.

This understanding came to me as finished the last few pages of his book, which I had been assigned to read for a class designed to reveal the breadth and width of Malcolm's influence. This gave me, a White-Devil, something that by the end of his life I think Malcolm intended for everyone to have: true freedom.

It would take many years to fully purge my system of the toxicity I experienced as a result of my experiences with Jose and My Father’s House. I would have to come to terms with my family’s implosion, and my father’s exodus. I would have to sift through the pain of how my relationship with Jose ended to reconnect with the good things that he taught me, things I hold onto even now. I would have to have my own child, and I’d need to learn how to be the kind of father she deserved after my marriage also ended in divorce.

I would learn that we are meant to fly too close to the sun, so long as we're wearing our own wings.

|

|

1. Arterburn, Stephen & Felton, Jack. Toxic Faith: Experiencing Healing from Painful Spiritual Abuse. Colorado Springs: WaterBrook Press. 1991.

2. Zerbe Taylor, Cheryl. "Religious Addiction: Obsession with Spirituality," Pastoral Psychology, No. 4, March 2002.

3. Haley, Alex & X, Malcolm. The Autobiography of Malcolm X: As Told to Alex Haley. New York: The Ballantine Publishing Group. 1964

2. Zerbe Taylor, Cheryl. "Religious Addiction: Obsession with Spirituality," Pastoral Psychology, No. 4, March 2002.

3. Haley, Alex & X, Malcolm. The Autobiography of Malcolm X: As Told to Alex Haley. New York: The Ballantine Publishing Group. 1964

Header art by T. Guzzio. Original photo by P. Casablanca.

CONNECT WITH TOM:

In addition to editing Prodigal's Chair, Tom is a teacher, father, husband, writer, artist, futbol fan and slightly maladjusted optimist. He lives in Beverly, Massachusetts with his wife and their cocker spaniel, Honey (who approves this message). You can connect with him on Twitter @t_guzzio, or via email at [email protected].

ADD YOUR VOICE:

ABOUT COMMENTS:

At Prodigal's Chair, thoughtful, honest interaction with our readers is important to our site's success. That's why we use Disqus as our comment / moderation system. Yes, you will need to login to leave a comment - with either your existing Facebook, Twitter, or Google+ account - or you can create your own free Disqus account. We do this for a couple of reasons: 1) to discourage trolling, and 2) to discourage spamming. Please note that Disqus will never post anything to your social network accounts unless you authorize it to do so. Finally, if you prefer you can always email comments directly to us by clicking here.