The United States of America is the only nation in the world founded not on a common culture, language, ethnicity, religion or due to geographic circumstance, but rather on a grand idea. This nation was anchored on the promise of democracy, of and by the people. However, for 144 years, from its conception in 1776 until the ratification of the 19th Amendment in1920, America was but a partial democracy, exclusionary, and as such, hypocritical. Anthony and her colleagues spent their lives crusading to balance the scales of justice by fulfilling the American promise of democracy for all. Susan B. Anthony may very well be America’s most influential historical figure you never learned about in school. This is her story, and her story is America’s story.

AN AMERICAN LIFE:

"The women of this nation in 1876, have greater cause for discontent, rebellion and revolution than the men of 1776." ― Susan B. Anthony

By G.E. Perine, via Wikimedia Commons.

By G.E. Perine, via Wikimedia Commons.

Susan Brownell Anthony was born on February 15th, 1820 in Adams, Massachusetts. She was the second of seven siblings, 2 boys and 5 girls. Susan’s mother, Lucy Read, raised each of the Anthony children with a strong moral compass. Their father, Daniel Anthony, was prominent in the temperance movement and was a well-known abolitionist. Susan B. Anthony’s siblings were all actively involved in pursuing social justice issues as well, and throughout their lives advocated on behalf of temperance, abolition, equal rights, and women’s suffrage.

Young Susan attended a local public school. At age seven she encountered a teacher who refused to teach her long division despite her obvious mathematical aptitude for the simple, matter-of-fact reason that she was female. Upon finding other schools in the area to be no better in this regard, Daniel Anthony started a school of his own where Susan, her siblings, and other local children, boys and girls together, received the curriculum with attention to equality. As a young adult, beginning in 1837, and for several years thereafter, Susan held a teaching position at the school. Over the next several years she would also teach at a variety of neighboring schools. As a teachers' union member, Anthony advocated for equal pay for male and female teachers, and for women to be allowed into the ranks of educational administration and management.

The first women’s suffrage movement was started by Elizabeth Cady Stanton in 1851. Anthony met Stanton at that time and the two embarked on a friendship and collegial relationship which lasted a lifetime. Together they founded the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) in 1869. The same year Susan B. Anthony’s role in the NWSA garnered her access to speak before Congress lobbying in favor of a woman’s suffrage amendment, an act she repeated every year for 37 years until her passing.

Arrested for voting illegally in the Presidential Election of 1872, because she was female, Anthony was tried, disallowed to speak at her trial on her own behalf, and found guilty. Famously, Susan never did pay the fine. Stanton and Anthony founded The Revolution, a newspaper whose mission was to promote women’s suffrage, and although short lived, it allowed them to broadcast a message which would sow the seeds of suffrage.

In her last year of life, at age 86, speaking publicly about how suffrage was within reach, Anthony stated in no uncertain terms “failure is impossible”. Susan B. Anthony died at home in Rochester, NY, on March 13, 1906. She would never realize the ultimate fruit of her labor, 14 years later, with the passage of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution, providing the right to vote to all American citizens, regardless of gender. The Anthony Family homestead in Rochester, NY, now serves as the National Susan B. Anthony Museum, and is a registered National Historic Landmark. In 1979 through 1981 the federal mint issued the Susan B. Anthony U.S. one dollar coin, making Anthony the first woman in America’s history to be featured on U.S. currency.

In 2020, one hundred years after the ratification of the 19th Amendment assuring for women the right to vote, we will hold a national celebration marking this milestone; the U.S. ten dollar bill will take on a new look, celebrating five women influential in the push for suffrage: Sojourner Truth, Alice Paul, Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and highest ranking among them, Susan B. Anthony.

Young Susan attended a local public school. At age seven she encountered a teacher who refused to teach her long division despite her obvious mathematical aptitude for the simple, matter-of-fact reason that she was female. Upon finding other schools in the area to be no better in this regard, Daniel Anthony started a school of his own where Susan, her siblings, and other local children, boys and girls together, received the curriculum with attention to equality. As a young adult, beginning in 1837, and for several years thereafter, Susan held a teaching position at the school. Over the next several years she would also teach at a variety of neighboring schools. As a teachers' union member, Anthony advocated for equal pay for male and female teachers, and for women to be allowed into the ranks of educational administration and management.

The first women’s suffrage movement was started by Elizabeth Cady Stanton in 1851. Anthony met Stanton at that time and the two embarked on a friendship and collegial relationship which lasted a lifetime. Together they founded the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) in 1869. The same year Susan B. Anthony’s role in the NWSA garnered her access to speak before Congress lobbying in favor of a woman’s suffrage amendment, an act she repeated every year for 37 years until her passing.

Arrested for voting illegally in the Presidential Election of 1872, because she was female, Anthony was tried, disallowed to speak at her trial on her own behalf, and found guilty. Famously, Susan never did pay the fine. Stanton and Anthony founded The Revolution, a newspaper whose mission was to promote women’s suffrage, and although short lived, it allowed them to broadcast a message which would sow the seeds of suffrage.

In her last year of life, at age 86, speaking publicly about how suffrage was within reach, Anthony stated in no uncertain terms “failure is impossible”. Susan B. Anthony died at home in Rochester, NY, on March 13, 1906. She would never realize the ultimate fruit of her labor, 14 years later, with the passage of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution, providing the right to vote to all American citizens, regardless of gender. The Anthony Family homestead in Rochester, NY, now serves as the National Susan B. Anthony Museum, and is a registered National Historic Landmark. In 1979 through 1981 the federal mint issued the Susan B. Anthony U.S. one dollar coin, making Anthony the first woman in America’s history to be featured on U.S. currency.

In 2020, one hundred years after the ratification of the 19th Amendment assuring for women the right to vote, we will hold a national celebration marking this milestone; the U.S. ten dollar bill will take on a new look, celebrating five women influential in the push for suffrage: Sojourner Truth, Alice Paul, Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and highest ranking among them, Susan B. Anthony.

TEACHER:

“Cautious, careful people, always casting about to preserve their reputation and social standing, never can bring about a reform....” ― Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony was, above all else, an educator. Formally, as a teacher in the classroom, and informally, across the spectrum of her life’s work in social reform, Anthony raised awareness of pressing civil rights issues, and stimulated dialogue, discussion and debate across the citizenry on matters as pressing as abolitionism, equality for women in the law, financial equality for women in the workplace, temperance, and of course, suffrage.

As a youngster, Anthony was schooled in the strict and formal Quaker tradition. Despite this, her parents were fairly liberal for their day and they impressed upon young Susan and her siblings, both male and female, the importance of self-reliance and equality. At the age of 17, Anthony attended a Quaker boarding school in Philadelphia--one of her first experiences away from her family and her home, as well as one of her first exposures to the dynamics of a large city.

As a youngster, Anthony was schooled in the strict and formal Quaker tradition. Despite this, her parents were fairly liberal for their day and they impressed upon young Susan and her siblings, both male and female, the importance of self-reliance and equality. At the age of 17, Anthony attended a Quaker boarding school in Philadelphia--one of her first experiences away from her family and her home, as well as one of her first exposures to the dynamics of a large city.

Photo by H.C. Ohlhous.

Photo by H.C. Ohlhous.

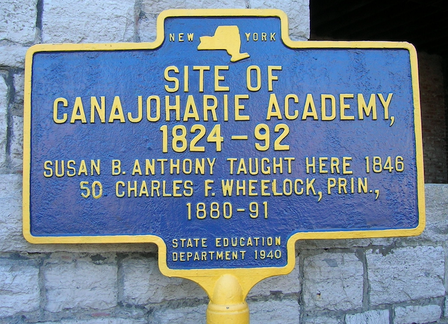

Susan B. Anthony’s first job was teaching in a classroom. She relished the opportunity to help students become literate, critical thinkers. Without this ability, she believed, society was doomed to stagnation, destined to repeat itself, and denied the opportunity to fulfill its democratic destiny. As headmistress of the Canajoharie Academy, an all-girls school in upstate New York, not far from her family home in Rochester, Susan’s positive influence grew from a single classroom to an entire student body and teaching staff.

As an educator Susan B. Anthony was vocal about equality in pay for male and female teachers. At the time, male teachers commonly earned up to ten times the wage of their female counterparts, and sometimes much more. Anthony’s first teaching job paid 110.00 annually, or about two dollars a week. At the 1853 New York State Teacher’s Convention Anthony raised this very point, though not before the men running the convention spent a half hour debating amongst themselves if it was, in fact, appropriate to allow a woman to speak at all. Greater sensibilities prevailed and Anthony proceeded to make her case for equality in pay. Later, at the 1857 Convention, Susan argued for the admission of African Americans to attend public schools, elementary through college. This idea was promptly shut down, deemed inappropriate for discussion. She also presented a case for male and female students to learn together, in the same schools and in the same classrooms. Her ideas were scorned, she was accused of attempting to derail the natural order, and one colleague stated in her proposals lurked “a vast social evil...a monster of social deformity.”

Focused on what she knew be just, Susan B. Anthony was not discouraged nor was she deterred. She strongly advocated her beliefs steeped in equality despite how poorly her message was received. Thanks to her perseverance, what was once ridiculed is today common practice under the law.

As an educator Susan B. Anthony was vocal about equality in pay for male and female teachers. At the time, male teachers commonly earned up to ten times the wage of their female counterparts, and sometimes much more. Anthony’s first teaching job paid 110.00 annually, or about two dollars a week. At the 1853 New York State Teacher’s Convention Anthony raised this very point, though not before the men running the convention spent a half hour debating amongst themselves if it was, in fact, appropriate to allow a woman to speak at all. Greater sensibilities prevailed and Anthony proceeded to make her case for equality in pay. Later, at the 1857 Convention, Susan argued for the admission of African Americans to attend public schools, elementary through college. This idea was promptly shut down, deemed inappropriate for discussion. She also presented a case for male and female students to learn together, in the same schools and in the same classrooms. Her ideas were scorned, she was accused of attempting to derail the natural order, and one colleague stated in her proposals lurked “a vast social evil...a monster of social deformity.”

Focused on what she knew be just, Susan B. Anthony was not discouraged nor was she deterred. She strongly advocated her beliefs steeped in equality despite how poorly her message was received. Thanks to her perseverance, what was once ridiculed is today common practice under the law.

ABOLITIONIST:

“No compromise with slaveholders… immediate and unconditional emancipation.” ― Susan B. Anthony

Sculpture in Susan B. Anthony Square, Rochester, NY. Photo by H.M. Larson via Wikimedia Commons.

Sculpture in Susan B. Anthony Square, Rochester, NY. Photo by H.M. Larson via Wikimedia Commons.

Between the years of 1845 and 1850 the Anthony family home in Rochester, New York became a hotbed of abolitionist philosophy, logistics, and activism. During this time Susan’s family was attending the local Unitarian church whose prime directive was promoting social justice. Many Unitarians devoted themselves to racial equality though the abolition of slavery. Sunday gatherings at the Anthony homestead were common, and well attended. Former slave and tireless abolitionist Frederick Douglass was one of those commonly in attendance. Douglass and Anthony forged a friendship and working relationship which lasted a lifetime.

Susan B. Anthony became a key figure within the newly formed American Anti-Slavery Society in the 1850s. Working collegially with influential abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison she managed a wide variety of tasks including organizing and booking speaking engagements, canvasing neighborhoods, issuing press releases, composing and delivering speeches and near-constant lecturing.

Susan B. Anthony became a key figure within the newly formed American Anti-Slavery Society in the 1850s. Working collegially with influential abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison she managed a wide variety of tasks including organizing and booking speaking engagements, canvasing neighborhoods, issuing press releases, composing and delivering speeches and near-constant lecturing.

During the period of 1860 - 1861, from her Rochester, New York base, Susan B. Anthony worked alongside Harriet Tubman, notable engineer of the Underground Railroad, in assisting fugitive slaves on their way to Canada. This was the cusp of the Civil War, national tensions ran high, and battle was in the air. Throughout 1861 Anthony’s lectures featuring her vision of racial equality and harmonious integration were met with protest and violence. In many cases Susan and the other speakers had to be escorted into and out of various venues by armed police to protect their safety. To be sure, many in the North, particularly New York, favored ending slavery, but many did not favor interfering in the business of other states, nor did they wish to go to war. Susan B. Anthony’s powerful, logic based arguments necessarily stirred the pot on this issue, and many on either side of the ideological coin formed mobs and clashed mightily with each other--in a sense, a micro scale civil war preceding the actual Civil War which would arrive in under two years. Of one of these episodes--a particular night in Syracuse--the Post Standard wrote “rotten eggs were thrown, benches broken, and knives and pistols gleamed in every direction”. Undeterred, Anthony and her colleagues continued to voice opinions and exercise their rights to freedom of speech, night after night, acts which took exceptional personal courage, strong fiber, and great vision.

Susan B. Anthony’s moral compass was set and strong early in life. In 1837, at the age of 16, Anthony was instrumental in collecting signatures in favor of ending slavery. At the time, even in the north, this was an unpopular position. Northerners certainly in large number abhorred the existence of slavery present across the south, but were not quick to act politically and interfere. They appeared content enough to leave the matter of slavery to each state’s independent decision and law. Anthony’s work as a teenager helped to educate and motivate those in the northern states to move to embrace a more aggressive, national anti-slavery position which culminated with the Civil War and Lincoln’s subsequent Emancipation Proclamation closing forever the horrific chapter of slavery in the United States.

Susan B. Anthony’s moral compass was set and strong early in life. In 1837, at the age of 16, Anthony was instrumental in collecting signatures in favor of ending slavery. At the time, even in the north, this was an unpopular position. Northerners certainly in large number abhorred the existence of slavery present across the south, but were not quick to act politically and interfere. They appeared content enough to leave the matter of slavery to each state’s independent decision and law. Anthony’s work as a teenager helped to educate and motivate those in the northern states to move to embrace a more aggressive, national anti-slavery position which culminated with the Civil War and Lincoln’s subsequent Emancipation Proclamation closing forever the horrific chapter of slavery in the United States.

WOMEN'S RIGHTS ACTIVIST:

"There never will be complete equality until women themselves help to make laws and elect lawmakers.” ― Susan B. Anthony

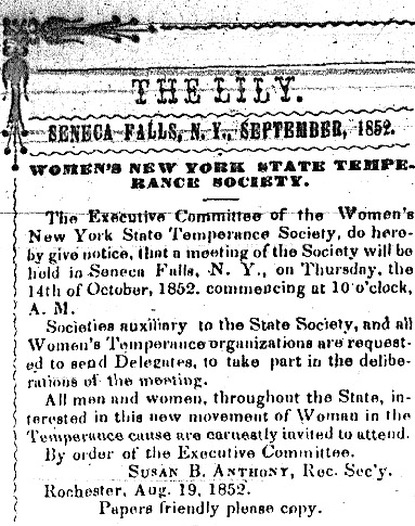

Announcement of Women's New York State Temperance Society Convention. Photo via the Model Editions Partnership.

Announcement of Women's New York State Temperance Society Convention. Photo via the Model Editions Partnership.

In Susan B. Anthony’s day, as was true across the United States of America from its founding in 1776, white women enjoyed very few guaranteed freedoms and sovereign rights in America, and African American women were protected by no rights whatsoever. The framers of the Constitution may have considered themselves wild eyed revolutionaries, thinkers and philosophers yet, fresh on the heels of victory in the American Revolution against the monarchy of the motherland, they had no place in their vision for women and people of color when it came to the overarching and uniquely American concept of liberty and justice for all. The revolution had not come, it seemed, for women. Their roles in this brand new country still mirrored the very same disenfranchised roles of women in England long before the battles at Lexington and Concord and Bunker Hill were fought and won.

In the family sphere of early America, husbands had complete legal control over the lives of their spouses. Any property the family had was, as bound by law, held by the husband in his name alone. This was true for the offspring. Children in a marriage were solemn property of the husband, subject to his rules and treatment, and in instances of divorce, children deferred directly to the husband uncontested, to remain in most cases forever estranged from their mother. For the first 150 years of our newly formed nation it was exceptionally rare for a woman to be employed outside of the home and to earn a salary. Throughout the course of Anthony’s life laws were firmly in place disallowing women from working in many occupations, and the idea of a woman going to work was frowned upon socially and seen as a weakness within the family, particularly a weakness of the husband. So it was, the prevailing culture distanced women from the social arena and from earning a wage. Married women were, in most instances, kept economically dependent on their husbands by way of common laws and the dominant social mores of the day. By entering into marriage a woman was quite simply giving up her very being and complete legal existence directly to her husband. Later in her career, in 1877, speaking on these very laws and the culture from which they emerged, Susan B. Anthony predicted an “epoch of single women”, noting “the woman who will not be ruled must live without marriage”.

Susan B. Anthony was frequently accused of attempting to dissolve the very foundations of marriage and family. This was never her argument, never her vision. However, those who stood to lose their social and legal power if women had the same rights as men (husbands specifically, and men in general) fought her on this point tooth and nail.

In 1949 at a meeting of the Daughters of Temperance a young Susan B. Anthony gave her first public speech. Temperance was a national debate, but also considered a woman’s rights issue. Drunken husbands were frequently abusive, and with no laws to protect women from domestic violence, wives were at the mercy of their intoxicated husbands. Because laws assured the wife had no access to the monetary holdings of the family, nor the property, alcoholic husbands could (and often did) drink through the family’s savings leaving wives and children destitute. In most instances divorce was not a legal option initiated by the woman without consent from the man, and even if the husband consented, the woman would lose full rights to her children and any claim to the family’s financial resources. Susan B. Anthony pursued temperance as a woman’s issue, and to that end a couple of years after making her first public speech Susan was scheduled to present at the largest temperance convention of its kind to that point, the New York Temperance Conference of 1852. Susan B. Anthony was disallowed from speaking, however, due to her status as a woman, and undeterred she and Elizabeth Cady Stanton formed the Woman’s State Temperance Society the following year. Stanton served as its first president and Anthony the vice president. The Society gained momentum and, soon thereafter, Susan prepared a speech to be delivered at the World Temperance Conference in New York City. The conference never heard that speech, however, because after engaging in a three day debate amongst themselves the board determined it was socially and professionally inappropriate to “allow” a woman to speak, and thus despite the progressive work she had done pushing forward the necessary itinerary of temperance, Susan B. Anthony was turned away.

Reflecting back on this experience and others like just it, Susan wrote "No advanced step taken by women has been so bitterly contested as that of speaking in public. For nothing which they have attempted, not even to secure the suffrage, have they been so abused, condemned and antagonized."

Susan B. Anthony was tireless pursuing equality under the law, equal pay for women, more lenient divorce laws from abusive husbands, equal access to speaking in a public forum, and opening up previously male-only professional positions to capable women. In short, she pursued undiluted equality for all women. Anthony had come to the conclusion that the one right above all else which she had to prioritize, must secure, was the right to vote--and from that one right only, she believed correctly, could come all other rights.

In the family sphere of early America, husbands had complete legal control over the lives of their spouses. Any property the family had was, as bound by law, held by the husband in his name alone. This was true for the offspring. Children in a marriage were solemn property of the husband, subject to his rules and treatment, and in instances of divorce, children deferred directly to the husband uncontested, to remain in most cases forever estranged from their mother. For the first 150 years of our newly formed nation it was exceptionally rare for a woman to be employed outside of the home and to earn a salary. Throughout the course of Anthony’s life laws were firmly in place disallowing women from working in many occupations, and the idea of a woman going to work was frowned upon socially and seen as a weakness within the family, particularly a weakness of the husband. So it was, the prevailing culture distanced women from the social arena and from earning a wage. Married women were, in most instances, kept economically dependent on their husbands by way of common laws and the dominant social mores of the day. By entering into marriage a woman was quite simply giving up her very being and complete legal existence directly to her husband. Later in her career, in 1877, speaking on these very laws and the culture from which they emerged, Susan B. Anthony predicted an “epoch of single women”, noting “the woman who will not be ruled must live without marriage”.

Susan B. Anthony was frequently accused of attempting to dissolve the very foundations of marriage and family. This was never her argument, never her vision. However, those who stood to lose their social and legal power if women had the same rights as men (husbands specifically, and men in general) fought her on this point tooth and nail.

In 1949 at a meeting of the Daughters of Temperance a young Susan B. Anthony gave her first public speech. Temperance was a national debate, but also considered a woman’s rights issue. Drunken husbands were frequently abusive, and with no laws to protect women from domestic violence, wives were at the mercy of their intoxicated husbands. Because laws assured the wife had no access to the monetary holdings of the family, nor the property, alcoholic husbands could (and often did) drink through the family’s savings leaving wives and children destitute. In most instances divorce was not a legal option initiated by the woman without consent from the man, and even if the husband consented, the woman would lose full rights to her children and any claim to the family’s financial resources. Susan B. Anthony pursued temperance as a woman’s issue, and to that end a couple of years after making her first public speech Susan was scheduled to present at the largest temperance convention of its kind to that point, the New York Temperance Conference of 1852. Susan B. Anthony was disallowed from speaking, however, due to her status as a woman, and undeterred she and Elizabeth Cady Stanton formed the Woman’s State Temperance Society the following year. Stanton served as its first president and Anthony the vice president. The Society gained momentum and, soon thereafter, Susan prepared a speech to be delivered at the World Temperance Conference in New York City. The conference never heard that speech, however, because after engaging in a three day debate amongst themselves the board determined it was socially and professionally inappropriate to “allow” a woman to speak, and thus despite the progressive work she had done pushing forward the necessary itinerary of temperance, Susan B. Anthony was turned away.

Reflecting back on this experience and others like just it, Susan wrote "No advanced step taken by women has been so bitterly contested as that of speaking in public. For nothing which they have attempted, not even to secure the suffrage, have they been so abused, condemned and antagonized."

Susan B. Anthony was tireless pursuing equality under the law, equal pay for women, more lenient divorce laws from abusive husbands, equal access to speaking in a public forum, and opening up previously male-only professional positions to capable women. In short, she pursued undiluted equality for all women. Anthony had come to the conclusion that the one right above all else which she had to prioritize, must secure, was the right to vote--and from that one right only, she believed correctly, could come all other rights.

THE REVOLUTION:

“Men, their rights and nothing more: Women, their rights and nothing less.” ― Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. Photo via Library of Congress.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. Photo via Library of Congress.

In the years leading up to the Civil War our young nation was filled with newsprint, radical in nature, pushing political and social belief systems and providing viewpoints from a variety angles. To be sure, traditional news outlets garnered the lion’s share of readership; however the tensions of pre-Civil War America necessitated media which wavered often widely from the center. In the years following the Civil War, many of these outlier publications died away, and the nation began to settle into the post-Civil War era, a period of healing, not division.

The women’s movement had, in the pre-Civil War years, associated itself closely with the abolitionist movement. Often, abolitionist media would also contain news and editorials of the women’s movement and was a primary vehicle for the women’s movement to further its voice and reach a larger readership. But with the Civil War in the nation’s rear view mirror, abolitionist media dried up and with it opportunities to get women’s rights issues out to the masses.

In 1868 Susan B. Anthony along with colleague and friend Elizabeth Cady Stanton founded The Revolution, a radical new newspaper which was the first of its kind in the United States. Published weekly from a home base in Rochester, NY, the driving force of the paper was to promote equality among the sexes in all regards from legal to financial to social--with women’s suffrage the ultimate goal.

The motto of The Revolution was simple and elegant: Men, their rights and nothing more: Women, their rights and nothing less. Unfortunately the financial obligations of running a weekly newspaper were rigorous and within a two year period The Revolution fell upon hard times. Anthony and Stanton passed ownership of the paper on to a wealthy women’s rights advocate who then toned down the “radical” nature of The Revolution bringing it more in line with moderate social thinking--which of course is not revolutionary at all. Nonetheless, during its short run, The Revolution gave Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton a platform from which they could communicate and educate people at large about the unconstitutional practice of barring women from having a voting say in their government. Years

later, during her famous trial speech, Anthony would remind the nation disallowing women the right to vote effectively reduces women from status of citizen to status of subject.

The women’s movement had, in the pre-Civil War years, associated itself closely with the abolitionist movement. Often, abolitionist media would also contain news and editorials of the women’s movement and was a primary vehicle for the women’s movement to further its voice and reach a larger readership. But with the Civil War in the nation’s rear view mirror, abolitionist media dried up and with it opportunities to get women’s rights issues out to the masses.

In 1868 Susan B. Anthony along with colleague and friend Elizabeth Cady Stanton founded The Revolution, a radical new newspaper which was the first of its kind in the United States. Published weekly from a home base in Rochester, NY, the driving force of the paper was to promote equality among the sexes in all regards from legal to financial to social--with women’s suffrage the ultimate goal.

The motto of The Revolution was simple and elegant: Men, their rights and nothing more: Women, their rights and nothing less. Unfortunately the financial obligations of running a weekly newspaper were rigorous and within a two year period The Revolution fell upon hard times. Anthony and Stanton passed ownership of the paper on to a wealthy women’s rights advocate who then toned down the “radical” nature of The Revolution bringing it more in line with moderate social thinking--which of course is not revolutionary at all. Nonetheless, during its short run, The Revolution gave Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton a platform from which they could communicate and educate people at large about the unconstitutional practice of barring women from having a voting say in their government. Years

later, during her famous trial speech, Anthony would remind the nation disallowing women the right to vote effectively reduces women from status of citizen to status of subject.

THE ROAD TO SUFFRAGE:

“It was we, the people; not we, the white male citizens; nor yet we, the male citizens; but we, the whole people, who formed the Union. And we formed it, not to give the blessings of liberty, but to secure them; not to the half of ourselves and the half of our posterity, but to the whole people - women as well as men. And it is a downright mockery to talk to women of their enjoyment of the blessings of liberty while they are denied the use of the only means of securing them provided by this democratic-republican government - the ballot.” ― Susan B. Anthony

In the years leading up to the Civil War, the abolitionist movement, driven in large part by William Lloyd Garrison and the American Anti-Slavery Society, and the women’s rights movement fueled by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, worked together, shared the stage at lectures and presentations, and often published their persuasive essays in the same periodicals and newspapers. Abolitionists also provided space in their newspapers at no cost allowing the woman’s movement to get its collective voice out to a much wider audience than otherwise would have been possible.

The women’s rights movement had precious little funding. Funding was always the chief obstacle for the women’s movement. Recall, women by and large were, by law, mainly disallowed from working, and their salaries if they did work outside the home at all, went, also by law, directly to their husbands--so soliciting donations from sympathetic minded readers was unrealistic. Also, women advocating openly for their rights and the rights of all women were subject to divorce by their husbands, loss of their homes, loss of rights to their children and even going to jail. Abolitionists on the other hand, while typically men, had donations coming in from a variety of wealthy sources, primarily business men from the North. Abolitionists believed in the concept of freedom and overall sympathized with the woman’s rights movement. Unity between the two groups was strong. Abolitionists and the women’s rights movement stood shoulder to shoulder against the greater American culture which enslaved African Americans and dismissed women as second rate citizens unworthy of protection under the law.

Anthony, Stanton and their associates were blindsided when, in 1860, a few years before the Civil War broke out, abolitionists pulled back on the relationship with the women’s rights movement and abandoned them of anticipated support at a highly critical time. Anthony was advocating greater leniency in divorce laws effectively allowing a woman swifter access to divorce in cases of violence, desertion, inhumane treatment, and financial neglect of the children. Abolitionists did mainly agree with Anthony and the woman’s rights movement, on this and other issues. Logistically, however, the abolitionists believed the woman's issues were distracting the nation from focusing on ending slavery and they made a plea to Susan B. Anthony and her colleagues in the women’s rights movement to put their cause on the back burner, for now, for what they argued was the greater common good, total emancipation. Infuriated and insulted, Anthony wrote to Lucy Stone, staunch women’s rights advocate: “The men, even the best of them, seem to think the women’s rights question should be waived for present. So let us do our own work, and in our own way.”

Over the course of her career, Susan B. Anthony is believed to have averaged between 75-100 speeches a year. Lecturing and speaking publicly was her only source of income from the time she left teaching at age 28 well into old age. The money she earned on her speaking circuits financed her personal life as well as much of the women’s movement. She formed the National Woman Suffrage Association, eventually merging with the competing American Woman Suffrage Association, and renamed the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). In the years after suffrage was achieved, the NAWSA would change its name one last time. It lives on today as the League of Women Voters.

During the Civil War the women’s rights movement came to a standstill as North battled South. In the years following the Union’s victory, during the period referred to as Reconstruction, three amendments to the United States Constitution, known as the Reconstruction Amendments, were enacted by Congress. The 13th Amendment provided for the abolition of the practice of slavery and involuntary labor. The 14th Amendment granted citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States,” including recently freed slaves. In addition, it forbade denying any person "life, liberty or property, without due process of law" or to "deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” The third and final Reconstruction Amendment is the15th Amendment which prohibits the federal and state governments from denying a citizen the right to vote based on that citizen's "race, color, or previous condition of servitude."

The women’s rights movement had precious little funding. Funding was always the chief obstacle for the women’s movement. Recall, women by and large were, by law, mainly disallowed from working, and their salaries if they did work outside the home at all, went, also by law, directly to their husbands--so soliciting donations from sympathetic minded readers was unrealistic. Also, women advocating openly for their rights and the rights of all women were subject to divorce by their husbands, loss of their homes, loss of rights to their children and even going to jail. Abolitionists on the other hand, while typically men, had donations coming in from a variety of wealthy sources, primarily business men from the North. Abolitionists believed in the concept of freedom and overall sympathized with the woman’s rights movement. Unity between the two groups was strong. Abolitionists and the women’s rights movement stood shoulder to shoulder against the greater American culture which enslaved African Americans and dismissed women as second rate citizens unworthy of protection under the law.

Anthony, Stanton and their associates were blindsided when, in 1860, a few years before the Civil War broke out, abolitionists pulled back on the relationship with the women’s rights movement and abandoned them of anticipated support at a highly critical time. Anthony was advocating greater leniency in divorce laws effectively allowing a woman swifter access to divorce in cases of violence, desertion, inhumane treatment, and financial neglect of the children. Abolitionists did mainly agree with Anthony and the woman’s rights movement, on this and other issues. Logistically, however, the abolitionists believed the woman's issues were distracting the nation from focusing on ending slavery and they made a plea to Susan B. Anthony and her colleagues in the women’s rights movement to put their cause on the back burner, for now, for what they argued was the greater common good, total emancipation. Infuriated and insulted, Anthony wrote to Lucy Stone, staunch women’s rights advocate: “The men, even the best of them, seem to think the women’s rights question should be waived for present. So let us do our own work, and in our own way.”

Over the course of her career, Susan B. Anthony is believed to have averaged between 75-100 speeches a year. Lecturing and speaking publicly was her only source of income from the time she left teaching at age 28 well into old age. The money she earned on her speaking circuits financed her personal life as well as much of the women’s movement. She formed the National Woman Suffrage Association, eventually merging with the competing American Woman Suffrage Association, and renamed the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). In the years after suffrage was achieved, the NAWSA would change its name one last time. It lives on today as the League of Women Voters.

During the Civil War the women’s rights movement came to a standstill as North battled South. In the years following the Union’s victory, during the period referred to as Reconstruction, three amendments to the United States Constitution, known as the Reconstruction Amendments, were enacted by Congress. The 13th Amendment provided for the abolition of the practice of slavery and involuntary labor. The 14th Amendment granted citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States,” including recently freed slaves. In addition, it forbade denying any person "life, liberty or property, without due process of law" or to "deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” The third and final Reconstruction Amendment is the15th Amendment which prohibits the federal and state governments from denying a citizen the right to vote based on that citizen's "race, color, or previous condition of servitude."

Susan B. Anthony arrested while attempting to register to vote, 1872. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Susan B. Anthony arrested while attempting to register to vote, 1872. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

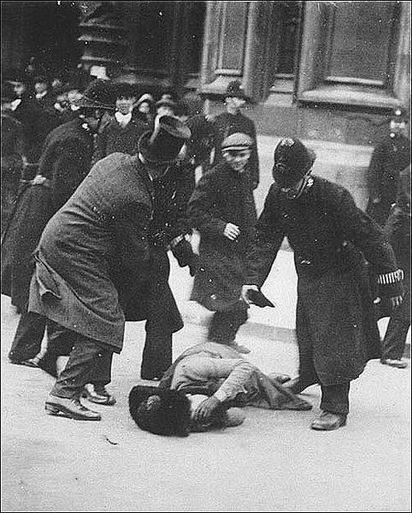

During Reconstruction no changes had been made with respect to a woman’s legal status in the United States of America. Amid the largest social order shake up this country has ever known vis a vis the emancipation of slaves and the Reconstruction Amendments, the subjected position of women in the world’s greatest “democracy” remained unchanged. Susan B. Anthony continued to push for women’s suffrage, of course, in the lecture hall, in newsprint, canvasing neighborhoods, and by any logical means possible. The fight had been long and hard, and the frustrations were many. Denied the opportunity to speak on multiple occasions, losing the support of the abolitionists right before the Civil War, and now seeing newly freed male former slaves granted the right to vote while still women were barred from participation in the democratic process, Susan B. Anthony was more dedicated than ever before to changing the laws systematically denying women the right to legal existence.

For Anthony, it was time to take another, considerably different, tactical approach. The newly ratified 14th Amendment granted citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States”. It made no mention or distinction between males and females, but rather denoted “all persons”. Susan B. Anthony and her suffragist colleagues, knowing themselves to be “persons born in the United States”, and thus presumably free to legally enjoy the rights of citizenship, of which voting is a principal right, made a major step forward in the push for women’s suffrage. Citing protection under the 14th Amendment, Anthony and fifty or so other women showed up at sites across Rochester, NY, to vote in the presidential election of 1872. Some of the women were, in fact, allowed to cast a ballot, and others were ushered out of the various polling venues. Susan B. Anthony, however, the face and voice of the women’s rights movement, was arrested on the spot. How could it be a crime, she questioned, for an American to vote in a U.S. Election?

The trial date was set, and the location was to be Monroe County, New York. Susan went to work lecturing in every town within the Monroe County limits raising the question “Is it a crime for a US citizen to vote?’ During the lecture crusade she was able to get her message out to nearly every potential juror in the county. When, at nearly the last moment, the trial was changed from Monroe to Ontario County, Anthony proceeded to give the same speech and convey the same message in all the towns and villages in Ontario County as she had done in Monroe County.

The trial began on June 17, 1873 and lasted three days. The story was national news, and reporters from across the country filed stories with their big city newspapers on all aspects of the proceedings. Due to a law in place at the time which disallowed a person on trial in a felony case from speaking on their own behalf, the powerful, logical and convincing voice of Susan B. Anthony was silenced. The following day Anthony was found guilty and fined 100.00, a sum she refused to pay and all evidence indicates she never did. On the final day the judge, Justice Hunt, asked Susan B. Anthony if she had anything to say for herself. Susan responded with what historian Ann Gordon called the “most famous speech in the history of agitation for woman suffrage”.

She spoke strongly and harshly against the court, its interpretations and its bias towards men. Her outrage of denial of rights under the law, despite being a natural born citizen, was articulately orated, and when Judge Hunt repeatedly insisted she stop talking, she continued eloquently onward, seizing the opportunity to state the case how her civil rights, natural rights, political rights, and judicial rights had all been ignored. Susan B. Anthony’s trial speech motivated masses of women and many men who, in a post-Civil War era, were better able to see beyond traditional norms, mores, and the overarching male dominant culture. A brief dramatization of Anthony’s famous trial speech may be found here.

For Anthony, it was time to take another, considerably different, tactical approach. The newly ratified 14th Amendment granted citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States”. It made no mention or distinction between males and females, but rather denoted “all persons”. Susan B. Anthony and her suffragist colleagues, knowing themselves to be “persons born in the United States”, and thus presumably free to legally enjoy the rights of citizenship, of which voting is a principal right, made a major step forward in the push for women’s suffrage. Citing protection under the 14th Amendment, Anthony and fifty or so other women showed up at sites across Rochester, NY, to vote in the presidential election of 1872. Some of the women were, in fact, allowed to cast a ballot, and others were ushered out of the various polling venues. Susan B. Anthony, however, the face and voice of the women’s rights movement, was arrested on the spot. How could it be a crime, she questioned, for an American to vote in a U.S. Election?

The trial date was set, and the location was to be Monroe County, New York. Susan went to work lecturing in every town within the Monroe County limits raising the question “Is it a crime for a US citizen to vote?’ During the lecture crusade she was able to get her message out to nearly every potential juror in the county. When, at nearly the last moment, the trial was changed from Monroe to Ontario County, Anthony proceeded to give the same speech and convey the same message in all the towns and villages in Ontario County as she had done in Monroe County.

The trial began on June 17, 1873 and lasted three days. The story was national news, and reporters from across the country filed stories with their big city newspapers on all aspects of the proceedings. Due to a law in place at the time which disallowed a person on trial in a felony case from speaking on their own behalf, the powerful, logical and convincing voice of Susan B. Anthony was silenced. The following day Anthony was found guilty and fined 100.00, a sum she refused to pay and all evidence indicates she never did. On the final day the judge, Justice Hunt, asked Susan B. Anthony if she had anything to say for herself. Susan responded with what historian Ann Gordon called the “most famous speech in the history of agitation for woman suffrage”.

She spoke strongly and harshly against the court, its interpretations and its bias towards men. Her outrage of denial of rights under the law, despite being a natural born citizen, was articulately orated, and when Judge Hunt repeatedly insisted she stop talking, she continued eloquently onward, seizing the opportunity to state the case how her civil rights, natural rights, political rights, and judicial rights had all been ignored. Susan B. Anthony’s trial speech motivated masses of women and many men who, in a post-Civil War era, were better able to see beyond traditional norms, mores, and the overarching male dominant culture. A brief dramatization of Anthony’s famous trial speech may be found here.

THE 19TH AMENDMENT:

“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”―19th Amendment to the United States Constitution

Susan B. Anthony continued to crusade for full rights of citizenship for women, and most importantly the right to vote. She spent her entire adult life promoting causes of social justice, the fruits of which are quite often taken for granted today.

In 1882, Anthony saw the cause of woman’s suffrage advance to a point where victory appeared to be near. The Senate appointed a Committee focused on Woman Suffrage. The committee announced it favored a constitutional amendment legalizing voting rights for women. Opposition from a number of senators, however, including many from the southern states, derailed that bill and thus effectively shut down woman suffrage in what had been its greatest advance yet.

When Anthony died, at age 86, on March 13, 1906 in Rochester, NY, women had still not gained the right to vote. Our democracy, the shining City on the Hill, rested on an unjust foundation. It promised liberty for all, but provided liberty only to some, depending on an X or Y chromosome. The majority of the nation, citizens in name only, were still denied the most basic of rights, and disenfranchised from democracy, denied the rights afforded all citizens under the 14th Amendment, denied the right to vote.

In 1882, Anthony saw the cause of woman’s suffrage advance to a point where victory appeared to be near. The Senate appointed a Committee focused on Woman Suffrage. The committee announced it favored a constitutional amendment legalizing voting rights for women. Opposition from a number of senators, however, including many from the southern states, derailed that bill and thus effectively shut down woman suffrage in what had been its greatest advance yet.

When Anthony died, at age 86, on March 13, 1906 in Rochester, NY, women had still not gained the right to vote. Our democracy, the shining City on the Hill, rested on an unjust foundation. It promised liberty for all, but provided liberty only to some, depending on an X or Y chromosome. The majority of the nation, citizens in name only, were still denied the most basic of rights, and disenfranchised from democracy, denied the rights afforded all citizens under the 14th Amendment, denied the right to vote.

On August 18, 1820, fourteen years after the death of Susan B. Anthony, Congress ratified the 19th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States. Known unofficially as the Anthony Amendment out of respect for the greatest advocate of woman’s suffrage, the 19th Amendment provides to all citizens, male and female alike, the right to vote in local, state and national elections. This right “shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.” What to this point had been only a partial democracy, masquerading as it did, pretending to offer full and complete democracy, had been elevated, vis a vis the 19th Amendment, to a government which would now truly be of, by, and for the people, male and female--and, thanks to the 14th Amendment, black and white. One hundred and forty four years after the signing of the Declaration of Independence, America took its greatest steps yet in fulfilling the promise of liberty and justice for all.

SIGNIFICANT EVENTS IN THE LIFE OF SUSAN B. ANTHONY:

1820

- Susan B. Anthony was born in Adams, a small town in the Berkshire hills of Massachusetts. Soon thereafter, her family moved to Rochester, NY where she lived the entirety of her life. The Anthony homestead is currently on the Register of Historic Places and serves as the National Susan B. Anthony Museum.

- Young Susan attended the first women's rights convention held in Seneca Falls, New York. Raised in a family whose liberal values and commitment to human rights were ever present Ms. Anthony drew from her background and family teachings as she made a life speaking on behalf of those disenfranchised from democracy, and from the pursuits of life, liberty and happiness.

- Gave her very first public speech at a women's temperance meeting. This would be the start of a lifetime of public speaking. In fact, SBA made her living from a seemingly endless lecture circuit right up into her 80s.

- Anthony organized the women’s state temperance society (with Elizabeth Cady Stanton) recognizing temperance to be a woman’s issue. Alcohol was rampant and alcoholic husbands often drank through the family savings something about which the wife had no legal recourse. Wives were more akin to property owned by the husband than equal partners in a relationship based on love and respect.

- Susan B. Anthony petitions for married women's property rights and protections for women from abusive spouses. At the time husbands had sole ownership of property and children. Women who advocated for themselves on this issue were often divorced by their husbands and left destitute as well as losing custody of their children.

- Susan pursued abolition serving as the New York State agent for the Anti-Slavery Society. Long time associate, colleague and friend of Harriet Tubman and Frederic Douglass, Ms. Anthony worked to end slavery on both a political front as well as vis a vis the Underground Railroad, helping fugitive slaves make their way to Canada.

- Anthony founded the National Woman Suffrage Association which, years after her death, when the 19th Amendment had passed and women had won the right to vote, changed its name from the NWSA to the League of Women Voters.

- Susan B. Anthony was famously arrested for voting illegally in Rochester, New York. She was tried during the United States Of America v. Susan B. Anthony. Disallowed from speaking on her own behalf at her trial, Anthony lost and was fined 100. dollars. She swore to never pay what she deemed an unjust the fine, and she never did.

REFERENCES:

- Biography of Susan B. Anthony. National Susan B. Anthony Museum & House.

- Chasing Freedom: The Life Journeys of Harriet Tubman and Susan B. Anthony. Grimes, Nikki & Wood, Michelle

- The Concise History of Woman Suffrage: Selections from History of Woman Suffrage, by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Matilda Joslyn Gage, and the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Buhle, Mary Jo & Buhle, Paul

- Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony: A Friendship That Changed the World. Coleman, Penny

- Failure Is Impossible: Susan B. Anthony in Her Own Words. Sherr, Lynn

- Failure is Impossible: The Story of Susan B.Anthony. Bohannon, Lisa F.

- The Feminist Revolution: A Story of the Three Most Inspiring and Empowering Women in American History: Susan B. Anthony, Margaret Sanger, and Betty Friedan. Archer, Jules

- The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony. Harper, Ida H.

- Not for Ourselves Alone: The Story of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. Burns, Ken & Ward, Geoffrey

- Susan B. Anthony. National Historic Park of New York.

- The Susan B. Anthony Women's Voting Rights Trial: A Headline Court Case. Monroe, Judy

FURTHER READING (FOR ALL AGES):

Picture Books about Susan B. Anthony & her Contemporaries

- Elizabeth Leads the Way: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the Right to Vote - A contemporary of Susan B. Anthony and fellow women’s rights activist, Elizabeth Cady Stanton played an integral role in the suffrage movement. This picture book tells the story of her life from a young girl to the leader she became. Stone, Tanya Lee (Author) & Gibbon, Rebecca (Illustrator)

- Friends for Freedom: The Story of Susan B. Anthony & Frederick Douglas - This picture book describes the unlikely friendship between Douglas and Anthony as they fought for equality for all Americans. Slade, Suzanne (Author) & Tagdell, Nicole (Illustrator)

- Heart on Fire: Susan B. Anthony Votes for President - Follow the story of the illegal and historic vote that Susan B. Anthony cast in the 1872 presidential election, resulting in her arrest and trial. Malaspina, Ann (Author) & James, Steve (Illustrator)

- If You Lived When Women Won Their Rights - This informational picture describes the limited life for American women in the mid 1800’s and how the women’s rights movement began and gained momentum. Kamma, Anna (Author) & Johnson, Pamela (Illustrator)

- Marching with Aunt Susan: Susan B. Anthony and the Fight for Women's Suffrage - Frustrated by all that girls cannot do in 1896, Bessie is inspired into action when Susan B. Anthony visits her small town. Murphy, Clair Rudolph (Author) & Schuett, Stacey (Illustrator)

- Susan B. Anthony - Accompanied by vibrant illustrations, this book tells the story of Susan B. Anthony’s fortitude in fighting for women’s rights. Wallner, Alexandra (Author & Illustrator)

- Two Friends: Susan B. Anthony and Frederick Douglas - Inspired by a Rochester, NY statue of Douglas and Anthony sharing tea, this book is the story of their separate but shared struggle for equality. Robbins, Dean (Author), & Alko, Selina (Illustrator), & Sean Qualls (Illustrator)

- You Want Woman to Vote, Lizzie Stanton? - Elizabeth (Lizzie) Cady Stanton recognized the inequality between men and women at a young age and eventually played a vital role in helping women gain the right to vote. This biographical picture book describe Lizzie’s role in this movement. Fritz, Jean (Author) & DiSalvo-Ryan, DyAnne (Illustrator)

- Susan B. Anthony: Fighter for Women’s Rights - This biographical book covers Susan’s early life and education as well as her fervent activism in the suffrage movement. Appropriate for students in Gr. 2-5. Hopkinson, Deborah (Author) & Bates, Amy June (Illustrator)

- Susan B. Anthony (TIME for Kids Nonfiction Readers) - This informational text begins with Susan B. Anthony’s young life and follows her involvement in the suffragist movement. Interspersed with photographs from Susan’s life, this book is appropriate for students in Gr. 3-6. Herweck, Dona

- Who Was Susan B. Anthony: Champion of Women’s Rights (Childhood of Famous Americans) - One of many books in a series, this biography details the life of Susan B. Anthony and her life-long dedication to women’s equality. Appropriate for students in Gr. 2-6. Helen Albee Monsell, Helen Albee

- Bio.com

- Humanities: The Magazine of the National Endowment for the Humanities

- Library of Congress: Women’s Suffrage

- National Susan B. Anthony Museum and House

- Susan B. Anthony Dares to Vote!

- The Elizabeth Cady Stanton & Susan B. Anthony Papers Project

- The Trial of Susan B. Anthony

Header art by M. Guzzio. Original photo via Twitter

CONNECT WITH CHRISTINE: |

CONNECT WITH CHRISTOPHER: |

|

Christine Gray taught middle school English Revere, MA where she is currently a Literacy Coach. Christine has Masters of Secondary Ed and is licensed reading specialist. She is passionate about providing access to books and choice to middle school readers. At home, Christine enjoys spending time with her husband, son, and daughter. Email her at [email protected].

|

Christopher Mattera, Ed.D. has been descending and photographing technical canyons on the Colorado Plateau for twenty-five years. His photography appears in Moab Canyoneering: Exploring Technical Canyons Around Moab, the newest guide book to technical canyoneering on the Colorado Plateau, recently published by Sharp End Publications. In addition he is an educator, and writer. Contact Chris at [email protected].

|

ADD YOUR VOICE:

ABOUT COMMENTS:

At Prodigal's Chair, thoughtful, honest interaction with our readers is important to our site's success. That's why we use Disqus as our comment / moderation system. Yes, you will need to login to leave a comment - with either your existing Facebook, Twitter, or Google+ account - or you can create your own free Disqus account. We do this for a couple of reasons: 1) to discourage trolling, and 2) to discourage spamming. Please note that Disqus will never post anything to your social network accounts unless you authorize it to do so. Finally, if you prefer you can always email comments directly to us by clicking here.