In Fever Pitch, Nick Hornby writes of how his obsession with Arsenal FC came to shape his life in unusual ways. He structures the memoir as a diary of sorts, compulsively measuring moments in his life against home and away fixtures, his results versus the team's. Hornby's devotion to the Gunners is such that he turns down invitations to weddings, birthday parties, and other events that conflict with Arsenal’s schedule - often to the frustration of those closest to him. He even lets an apartment within walking distance of the pitch, thus fulfilling a "pitiful twenty-year ambition" of naked fandom. But his book is less of an exploration of his foibles than an attempt at explaining their staying power. "Why," he asks, "has the relationship that began as a schoolboy crush endured for nearly a quarter of a century, longer than any other relationship I have made of my own free will?" While Fever Pitch is unapologetically personal, and - well - unapologetic about one man’s obsessive love of a sports team, Hornby's look at his personal history through the lens of football does reveal something about society in general and sports culture in particular.

Hornby is a fan, and Fever Pitch shows just how far one fan's obsession with sport can infiltrate all levels of his or her life. But he is, after all, just one fan. The fact that Emirates Stadium, where Arsenal now plays its home matches, regularly sells out its 65,000 plus seats illustrates how fandom can unite disparate individuals into groups – whose size can rival the populations of small towns – behind a bunch of guys playing a game. A game. Not a religious or political belief, but a game.

Hornby is a fan, and Fever Pitch shows just how far one fan's obsession with sport can infiltrate all levels of his or her life. But he is, after all, just one fan. The fact that Emirates Stadium, where Arsenal now plays its home matches, regularly sells out its 65,000 plus seats illustrates how fandom can unite disparate individuals into groups – whose size can rival the populations of small towns – behind a bunch of guys playing a game. A game. Not a religious or political belief, but a game.

True, the religious and political beliefs of sports fans are often projected onto the teams they follow. Franklin Foer, in his wonderful book, How Soccer Explains the World: An Unlikely Theory of Globalization describes, for example, how free market football in Glasgow, Scotland has failed to erase centuries old religious conflict. Free market apologists will argue that the rising tide of world capitalism raises everyone’s boat indiscriminately, regardless of which flags they fly or whose kit they wear. But in the city that gave us Adam Smith and the market’s “invisible hand,” Protestant Rangers fans refuse to share safe harbor with Catholic Celtic supporters, despite the bright and shiny façade free trade has given contemporary Glasgow. As the Celtic-Rangers derby approaches, the cosmopolitan sense of community rooted in the modern Glaswegian culture of mass consumption steps aside and the city is thrust back in time to the Reformation Era with alarmingly measurable consequences: during derby weekends, Foer notes, "admissions in the city's emergency wards increase nine-fold."

The love of one team (or is it the hatred of another) and the often-irrational acts it can inspire is not limited to old-world Euro-tribalism. It happens here in the States, too. Just look at the most storied of American sports rivalries, our version of Scotland's Old Firm: the New York Yankees versus the Boston Red Sox. Mike Vaccarro explores the rivalry in-depth in his very readable Emperors and Idiots: The Hundred Year Rivalry Between the Yankees and Red Sox, From the Very Beginning to the End of the Curse.

"Having grown up a fan of neither team but an admirer of both,” Vaccarro brings an outsider's eye to a rivalry that, for many fans blinded by passion simply boils down to irrational declarations of how much the other team sucks. While there have been enough on-field battles – both physical and statistical – between the two teams to stoke the flames, these are often ignored by fans quick to latch onto the “Curse of the Bambino” as the main reason for Boston’s demise and the Yankee’s ascension in the baseball food chain after 1918. But to reduce the origins of the rivalry to a “curse” brought on by Sox owner Harry Frazee’s trading of a cocky young pitcher (with a penchant for hitting the long ball) to the Yankees denies the rivalry’s true origins. The roots of the enmity between the Sox and Yanks can be traced to an event that happened when George Herman Ruth was eight years old, the Red Sox were the Boston Pilgrims, and the Yankees were an upstart team called the Highlanders. It was born out of the inability to assign responsibility for a brutal collision between players most fans on either side of baseball's "Great Fault Line" aren’t able to name today.

But for fans, it's not about who threw the proverbial first punch anymore, nor is it about the curse – that was broken when the Red Sox came from behind to beat the Yankees for the American League Pennant en route to winning the 2004 World Series. For the fans, the rivalry has become an end in itself. In Boston and New York players come, go, and move between the two clubs (over 200 have worn both uniforms over the decades). The pendulum of success has swung from the Red Sox, who dominated baseball early in its modern history, to the Yankees, and back to Boston again. Yet regardless of either team’s line-ups or the fortunes their arms and bats bring, the rivalry’s one true constant has been the fans and their unending need to hate one another. This hatred has led to acts that run from absurdly childish to profoundly disturbing.

The love of one team (or is it the hatred of another) and the often-irrational acts it can inspire is not limited to old-world Euro-tribalism. It happens here in the States, too. Just look at the most storied of American sports rivalries, our version of Scotland's Old Firm: the New York Yankees versus the Boston Red Sox. Mike Vaccarro explores the rivalry in-depth in his very readable Emperors and Idiots: The Hundred Year Rivalry Between the Yankees and Red Sox, From the Very Beginning to the End of the Curse.

"Having grown up a fan of neither team but an admirer of both,” Vaccarro brings an outsider's eye to a rivalry that, for many fans blinded by passion simply boils down to irrational declarations of how much the other team sucks. While there have been enough on-field battles – both physical and statistical – between the two teams to stoke the flames, these are often ignored by fans quick to latch onto the “Curse of the Bambino” as the main reason for Boston’s demise and the Yankee’s ascension in the baseball food chain after 1918. But to reduce the origins of the rivalry to a “curse” brought on by Sox owner Harry Frazee’s trading of a cocky young pitcher (with a penchant for hitting the long ball) to the Yankees denies the rivalry’s true origins. The roots of the enmity between the Sox and Yanks can be traced to an event that happened when George Herman Ruth was eight years old, the Red Sox were the Boston Pilgrims, and the Yankees were an upstart team called the Highlanders. It was born out of the inability to assign responsibility for a brutal collision between players most fans on either side of baseball's "Great Fault Line" aren’t able to name today.

But for fans, it's not about who threw the proverbial first punch anymore, nor is it about the curse – that was broken when the Red Sox came from behind to beat the Yankees for the American League Pennant en route to winning the 2004 World Series. For the fans, the rivalry has become an end in itself. In Boston and New York players come, go, and move between the two clubs (over 200 have worn both uniforms over the decades). The pendulum of success has swung from the Red Sox, who dominated baseball early in its modern history, to the Yankees, and back to Boston again. Yet regardless of either team’s line-ups or the fortunes their arms and bats bring, the rivalry’s one true constant has been the fans and their unending need to hate one another. This hatred has led to acts that run from absurdly childish to profoundly disturbing.

Workers dig up a David Ortiz buried in the foundation of Yankee Stadium. Photo: A Chevrestt

Workers dig up a David Ortiz buried in the foundation of Yankee Stadium. Photo: A Chevrestt

In April of 2008, Red Sox fan and stonemason Gino Castignoli attempted to create a curse of his own. During the construction of the new Yankee Stadium, Castignoli – a Sox fan since 1975 – sunk a David Ortiz jersey into the stadium’s foundation, much to the annoyance of Yankee brass. “I hope his coworkers kick the shit out of him,” fumed Senior Yankees VP Hank Steinbrenner, adding that Yankee fans need not worry about any supernatural ramifications of Castignoli’s act, “It’s a bunch of bullshit.”

Bullshit? The jersey was quickly dug up after the New York Post broke the story, and one fan, at least was worried enough to retaliate. While attending a Phish concert at Fenway Park, Ian Ferris brought along leftover grass seed from the new Yankee Stadium. "I'm a lifelong Yankee fan and someone buried an Ortiz jersey in the cement at our stadium in the Bronx, so this was a little retribution," Ferris explained. "It's all in good fun. It wasn't meant to be malicious in any way. I just wanted to add fuel to the rivalry fire."

But sometimes it’s not all good, let alone fun.

Just a month after Castignoli's act, a Nashua, New Hampshire woman named Ivonne Hernandez rammed her car into a crowd of people outside of a bar, killing 29 year old Matthew Beaudoin. According to prosecutors, “she never braked, and she accelerated at a high speed for about 200 feet,” all because Beaudoin and his friends – all Red Sox fans – taunted her for following the Yankees. In Falmouth, Mass that July Red Sox fan Robert Correia allegedly beat a man with a baseball bat because the man’s car sported a Yankees bumper sticker. Later that summer a Red Sox fan filed a lawsuit against the Yankees and two of their fans after an altercation at Yankee Stadium. After having words in the stands, the suit claims that the Massachusetts resident was “viciously attacked and physically assaulted” by the two men when he went to a concession stand.

It’s natural to see the rivalry between the Red Sox and the Yankees as an extension of the educational, economic, and cultural competition that has existed between Boston and New York since our Nation’s founding. But all metaphors aside, the impulse that drove Hernandez to step on the gas, caused Castignoli to throw a Papi jersey into the mix, and left Hornby looking for living arrangements based on a place’s proximity to a soccer stadium is rooted in a singularly skewed sense of personal identity that seems to transcend the accepted norms and mores of community membership. The actions I’ve described are notable because they’re, well… not normal. These acts are outliers, representing the extremes of fandom.

But even a casual fan can understand these extremes. They don’t condone these acts, but at the surface, they understand.

It hasn't been that way for me.

When Fever Pitch was adapted for a US film audience, the producers placed the narrative in Boston, and cast “Hornby” as a Red Sox fan. I’ve always liked baseball. I even played little league for a year, but I’ve never looked to any one team (in any one sport) the way the characters in both Fever Pitches do. So-called “true” fans have called this lack of sports centeredness a moral defect – a sure sign that momma didn’t raise me right. It’s not. It’s simply a function of time and geography. It’s taken as a given that the vast majority of American boys grow up entranced by sports, and while I was very much a sports fan as a kid, I was never half as interested in a particular team as Hornby is. I am convinced that this is a result of me coming of age in Las Vegas.

Bullshit? The jersey was quickly dug up after the New York Post broke the story, and one fan, at least was worried enough to retaliate. While attending a Phish concert at Fenway Park, Ian Ferris brought along leftover grass seed from the new Yankee Stadium. "I'm a lifelong Yankee fan and someone buried an Ortiz jersey in the cement at our stadium in the Bronx, so this was a little retribution," Ferris explained. "It's all in good fun. It wasn't meant to be malicious in any way. I just wanted to add fuel to the rivalry fire."

But sometimes it’s not all good, let alone fun.

Just a month after Castignoli's act, a Nashua, New Hampshire woman named Ivonne Hernandez rammed her car into a crowd of people outside of a bar, killing 29 year old Matthew Beaudoin. According to prosecutors, “she never braked, and she accelerated at a high speed for about 200 feet,” all because Beaudoin and his friends – all Red Sox fans – taunted her for following the Yankees. In Falmouth, Mass that July Red Sox fan Robert Correia allegedly beat a man with a baseball bat because the man’s car sported a Yankees bumper sticker. Later that summer a Red Sox fan filed a lawsuit against the Yankees and two of their fans after an altercation at Yankee Stadium. After having words in the stands, the suit claims that the Massachusetts resident was “viciously attacked and physically assaulted” by the two men when he went to a concession stand.

It’s natural to see the rivalry between the Red Sox and the Yankees as an extension of the educational, economic, and cultural competition that has existed between Boston and New York since our Nation’s founding. But all metaphors aside, the impulse that drove Hernandez to step on the gas, caused Castignoli to throw a Papi jersey into the mix, and left Hornby looking for living arrangements based on a place’s proximity to a soccer stadium is rooted in a singularly skewed sense of personal identity that seems to transcend the accepted norms and mores of community membership. The actions I’ve described are notable because they’re, well… not normal. These acts are outliers, representing the extremes of fandom.

But even a casual fan can understand these extremes. They don’t condone these acts, but at the surface, they understand.

It hasn't been that way for me.

When Fever Pitch was adapted for a US film audience, the producers placed the narrative in Boston, and cast “Hornby” as a Red Sox fan. I’ve always liked baseball. I even played little league for a year, but I’ve never looked to any one team (in any one sport) the way the characters in both Fever Pitches do. So-called “true” fans have called this lack of sports centeredness a moral defect – a sure sign that momma didn’t raise me right. It’s not. It’s simply a function of time and geography. It’s taken as a given that the vast majority of American boys grow up entranced by sports, and while I was very much a sports fan as a kid, I was never half as interested in a particular team as Hornby is. I am convinced that this is a result of me coming of age in Las Vegas.

No major or minor American sport would dare place a professional franchise in Sin City, though – from time to time – there are flirtations. Cast aside the fear of being associated with gangsters and gambling (this is, after all, the state that decided the image that best represented it on a quarter was a wild horse and not the slot machine that consumes so many of said quarters), and you’re left with a fan base whose dominant feature is transiency. No one is from Vegas. People live there, but they aren’t from there, and when they scan the sports pages, they’re likely to search for a bar in their neighborhood that’s aligned with their favorite teams from home.

I was one of those people. When I was five, my family moved to Vegas from Buffalo, New York. Included in the inventory of what I took along for the trip were the Buffalo Bills, the New York Yankees, and the Buffalo Sabres. But I was too young to truly understand what it meant to be a fan in general, let alone a fan of these teams in particular. Like most things passed on to a five year old, these teams were chosen for me. I never really had a chance to develop a love for them on my own. When my family fell apart shortly after the move, the questions I struggled with were far greater than, “who’s your favorite Bills player?” My parents sat me down and asked me whom I wanted to live with. Seriously. If I could even name a player other than OJ Simpson, and I’m sure I couldn’t, the answer wouldn’t be close at hand.

I – along with a brother and a sister – stayed in Vegas with my mom, while my father took another brother and sister back to Buffalo with him. As time went on, following the Yankees, Sabres, and the Bills was less about the teams and more about coping, about holding onto to a past when my family was whole. It was easy to root for the successful Yankees teams of the late 70s and early 80s, especially after they signed Tommy John in 1979 (since “John” is my middle name, family members had been calling me “Tommy John” since I toddled). Before we moved to Vegas, a pre-white Bronco OJ used to frequent a bar my dad ran in Buffalo called the Little Red Inn, and my mother worked as a waitress at a club in Memorial Auditorium where the Sabres played. But as I grew older, the tenuous strands linking me to Buffalo grew weaker and weaker. By the time I was in middle school, I had no family in Western NY that I stayed in any kind of regular contact with, and while my interest in sports grew along with my body, my interest in Buffalo sports was something that arced and drifted wide-right as I moved towards adulthood. Increasingly, I became more and more a fan of players instead of teams, reveling in Michael Jordan’s greatness, for example as opposed to the Bulls (who had won three championships before I ever visited Chicago). I became what a good friend of my derisively calls "a bandwagoner."

The nature of my fandom changed when I moved to Boston in 2006. I suddenly had access to four storied franchises from America’s big-four sports leagues (the NFL’s New England Patriots, the NHL’s Boston Bruins, the Boston Celtics of the NBA, and of course MLB’s Red Sox). Additionally, the Boston market was big enough to support teams from upstart leagues like Major League Lacrosse’s Boston Cannons, or World Team Tennis’ Boston Lobsters, and Major League Soccer’s New England Revolution (and the region would soon welcome a women’s professional soccer team in the Boston Breakers). Suddenly, I went from a town that had more cheap buffets than sports teams to one with a metaphorical potluck of teams to cheer for and follow. And I did follow, at first out of curiosity and a general love of sports, and then due to compulsion.

I was one of those people. When I was five, my family moved to Vegas from Buffalo, New York. Included in the inventory of what I took along for the trip were the Buffalo Bills, the New York Yankees, and the Buffalo Sabres. But I was too young to truly understand what it meant to be a fan in general, let alone a fan of these teams in particular. Like most things passed on to a five year old, these teams were chosen for me. I never really had a chance to develop a love for them on my own. When my family fell apart shortly after the move, the questions I struggled with were far greater than, “who’s your favorite Bills player?” My parents sat me down and asked me whom I wanted to live with. Seriously. If I could even name a player other than OJ Simpson, and I’m sure I couldn’t, the answer wouldn’t be close at hand.

I – along with a brother and a sister – stayed in Vegas with my mom, while my father took another brother and sister back to Buffalo with him. As time went on, following the Yankees, Sabres, and the Bills was less about the teams and more about coping, about holding onto to a past when my family was whole. It was easy to root for the successful Yankees teams of the late 70s and early 80s, especially after they signed Tommy John in 1979 (since “John” is my middle name, family members had been calling me “Tommy John” since I toddled). Before we moved to Vegas, a pre-white Bronco OJ used to frequent a bar my dad ran in Buffalo called the Little Red Inn, and my mother worked as a waitress at a club in Memorial Auditorium where the Sabres played. But as I grew older, the tenuous strands linking me to Buffalo grew weaker and weaker. By the time I was in middle school, I had no family in Western NY that I stayed in any kind of regular contact with, and while my interest in sports grew along with my body, my interest in Buffalo sports was something that arced and drifted wide-right as I moved towards adulthood. Increasingly, I became more and more a fan of players instead of teams, reveling in Michael Jordan’s greatness, for example as opposed to the Bulls (who had won three championships before I ever visited Chicago). I became what a good friend of my derisively calls "a bandwagoner."

The nature of my fandom changed when I moved to Boston in 2006. I suddenly had access to four storied franchises from America’s big-four sports leagues (the NFL’s New England Patriots, the NHL’s Boston Bruins, the Boston Celtics of the NBA, and of course MLB’s Red Sox). Additionally, the Boston market was big enough to support teams from upstart leagues like Major League Lacrosse’s Boston Cannons, or World Team Tennis’ Boston Lobsters, and Major League Soccer’s New England Revolution (and the region would soon welcome a women’s professional soccer team in the Boston Breakers). Suddenly, I went from a town that had more cheap buffets than sports teams to one with a metaphorical potluck of teams to cheer for and follow. And I did follow, at first out of curiosity and a general love of sports, and then due to compulsion.

Paul Revere, in the style of John Singleton Copley, by Joanne Kaliontzis

Paul Revere, in the style of John Singleton Copley, by Joanne Kaliontzis

You can’t live in Boston and try to make it your home without accepting – for better or worse – the impact sports has on the area’s culture. Fenway Park is every bit as iconic as the Old North Church, Bobby Orr’s diving goal as revered as Paul Revere’s ride. You can sit next to a statue of Red Auerbach as you watch historical re-enactors teach tourists about Sam Adams on the steps of Faneuil Hall. For the vast majority of Bostonians, sport is a palpable presence 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

It also didn’t hurt that Boston sports franchises were riding an unprecedented wave of success as I arrived, with the Sox taking another World Series title in 2007, and again in 2013. Coming off Super Bowl victories in 2001, 2003, and again in 2004, the Patriots made two unsuccessful Super Bowl appearances in 2007 and 2011 before winning it for the fourth time in 2014. The Bruins would raise the Stanley Cup in 2011, and play for it again in 2013 without success. And – while the Celtics were well removed from their glory days when I arrived in the city – that would soon change in a way that would allow me to easily (and authentically) embrace them as well. In moves that fit perfectly with my cult-of-personality form of fandom, the Celtics would land two of my favorite players in Ray Allen and Kevin Garnett the summer after my arrival. These two players would combine with Celtic stalwart Paul Pierce to form “The Boston Three Party,” leading the team to the 2008 Championship and another NBA Finals appearance in 2010.

Steadily, I’ve been learning how to be a different kind of sports fan. I find myself looking forward to a season’s coming in ways I never have before as I transform into something I never thought I could be: a loyal fan of a single area’s offering of professional sports teams. Since my arrival I’ve been to numerous games, including a few playoff contests. I stood and watched the Duck Boats roll by after the Bruins won the Cup, soaking in the moment with thousands of other black and yellow clad fans. A sports talk radio station has come to occupy one of the presets in my car stereo, and I spend time discussing the merits of each rumored potential soccer-specific stadium site the Revolution will – hopefully – one day call home (I’m pulling for the former Wonderland dog track in Revere. It’s on the Blue Line and close to the commuter rail, and I have a good friend who lives right down the street).

It also didn’t hurt that Boston sports franchises were riding an unprecedented wave of success as I arrived, with the Sox taking another World Series title in 2007, and again in 2013. Coming off Super Bowl victories in 2001, 2003, and again in 2004, the Patriots made two unsuccessful Super Bowl appearances in 2007 and 2011 before winning it for the fourth time in 2014. The Bruins would raise the Stanley Cup in 2011, and play for it again in 2013 without success. And – while the Celtics were well removed from their glory days when I arrived in the city – that would soon change in a way that would allow me to easily (and authentically) embrace them as well. In moves that fit perfectly with my cult-of-personality form of fandom, the Celtics would land two of my favorite players in Ray Allen and Kevin Garnett the summer after my arrival. These two players would combine with Celtic stalwart Paul Pierce to form “The Boston Three Party,” leading the team to the 2008 Championship and another NBA Finals appearance in 2010.

Steadily, I’ve been learning how to be a different kind of sports fan. I find myself looking forward to a season’s coming in ways I never have before as I transform into something I never thought I could be: a loyal fan of a single area’s offering of professional sports teams. Since my arrival I’ve been to numerous games, including a few playoff contests. I stood and watched the Duck Boats roll by after the Bruins won the Cup, soaking in the moment with thousands of other black and yellow clad fans. A sports talk radio station has come to occupy one of the presets in my car stereo, and I spend time discussing the merits of each rumored potential soccer-specific stadium site the Revolution will – hopefully – one day call home (I’m pulling for the former Wonderland dog track in Revere. It’s on the Blue Line and close to the commuter rail, and I have a good friend who lives right down the street).

I also met, fell in love with, and married someone who was born and raised here. Roots are a rarity in Vegas. During our time together, my wife and I have taken annual trips to Fenway Park, watched from seats as high as the rafters (a surprisingly good vantage point) as the Celtics beat the Knicks in a thrilling playoff game (despite later going on to lose the series), and sat caught in the cross-fire as local Brazilians and Portuguese fans cheered on their respective national soccer teams in a sold out international friendly at Gillette Stadium. I am not, and probably never will be, as devoted a fan as Hornby, nor will I begrudge anyone’s right to root for whatever team they wish… even the Yankees. But now I understand why, when people move to Vegas, their teams come with. It’s not simply the dearth of pro sports teams in Las Vegas that causes new arrivals to continue to root for teams from home; it’s how sport helps you define what home is.

Looking back, I innately grasped at this idea when I was five, but it has only become really clear to me after April 15th, 2013 when two pressure cooker bombs exploded at the finish line of the 117th running of the Boston Marathon.

I wasn’t in Boston that day – I was, ironically, in New York visiting my daughter – but as soon as I heard about the blasts my mind immediately turned to friends who were. You can’t live in the Boston area and not know someone who is running in the Marathon, or who is cheering on someone who is running. As information poured in over the next few days, I would learn that one of my best friends – a man who would later stand with me at my wedding – was yards away from the blasts. A former student of the middle school I work at would be unjustly labeled a bag man in an irresponsible report in the New York Post; his love of running and his dark skin putting him in the awkward position of the wrongly accused. My mind would swim around the fact that my daughter and I had visited the finish line just a month before. Figurative shockwaves from the blasts stretched beyond Boylston Street in the days that followed. Once two viable suspects were named, Boston was locked down as the hunt for them intensified. The city became a ghost town as those trapped in their homes were riveted to their televisions, the events leading up to the capture of the surviving suspect unfolding in real-time across the screens.

Looking back, I innately grasped at this idea when I was five, but it has only become really clear to me after April 15th, 2013 when two pressure cooker bombs exploded at the finish line of the 117th running of the Boston Marathon.

I wasn’t in Boston that day – I was, ironically, in New York visiting my daughter – but as soon as I heard about the blasts my mind immediately turned to friends who were. You can’t live in the Boston area and not know someone who is running in the Marathon, or who is cheering on someone who is running. As information poured in over the next few days, I would learn that one of my best friends – a man who would later stand with me at my wedding – was yards away from the blasts. A former student of the middle school I work at would be unjustly labeled a bag man in an irresponsible report in the New York Post; his love of running and his dark skin putting him in the awkward position of the wrongly accused. My mind would swim around the fact that my daughter and I had visited the finish line just a month before. Figurative shockwaves from the blasts stretched beyond Boylston Street in the days that followed. Once two viable suspects were named, Boston was locked down as the hunt for them intensified. The city became a ghost town as those trapped in their homes were riveted to their televisions, the events leading up to the capture of the surviving suspect unfolding in real-time across the screens.

When the suspects who targeted one of the Nation’s oldest sporting events were killed or captured, Bostonians used sport to begin healing and to return to normalcy. A makeshift memorial sprung up in Copley Square, with many marathon participants leaving their shoes as a way of reclaiming the site as their own. In a show of solidarity with the city and team they so often despise, the Yankees played Neil Diamond’s “Sweet Caroline” in the third inning of their April 16th game against the Arizona Diamondbacks, their fans singing along to the Fenway staple as a ribbon declaring “New York Stands with Boston” flashed across the scoreboard. And as the Bruins, Celtics, Revolution, and Red Sox resumed play, each team took time to honor those whose lives were impacted by the event – something that would continue in the coming months as victims and responders recovered from injuries sustained during the attack. T-shirts and ribbons declaring “Boston Strong” in the yellow and blue colors of the Boston Athletic Association, as well as “B Strong” buttons and hats – the “B” echoing the Red Sox’s famous logo – were ubiquitous at these events and in Boston in general as we rallied around the city by rallying around our teams.

No moment better illustrates the ability of sport to define and defend “home” for me than the Red Sox’s return to Fenway Park on April 20th. In the ceremony leading up to the game, slugger David Ortiz – who has been with the Sox since 2003, and who became a US citizen in 2006 – stepped up to the microphone: “This jersey that we're wearing today it doesn't say 'Red Sox.' It says, 'Boston.' We want to thank you for you, Mayor Menino, Governor Patrick, the whole police department, for the great job that they did this past week." Then he uttered the words that would launch hundreds of FCC complaints while capturing the way everyone living in Boston felt at the time: "This is our fucking city. And nobody gonna to dictate our freedom. Stay strong!"

It would be wrong for me to claim that the Boston Marathon bombing and the ensuing tragedy and triumph that it produced made me a Boston sports fan. But as I watched Big Papi speak, I began to realize that Boston was becoming home to me in ways Buffalo and Vegas never were. Boston sports had a huge hand in that, and I was grateful for the role they had in helping what has become my city heal.

No moment better illustrates the ability of sport to define and defend “home” for me than the Red Sox’s return to Fenway Park on April 20th. In the ceremony leading up to the game, slugger David Ortiz – who has been with the Sox since 2003, and who became a US citizen in 2006 – stepped up to the microphone: “This jersey that we're wearing today it doesn't say 'Red Sox.' It says, 'Boston.' We want to thank you for you, Mayor Menino, Governor Patrick, the whole police department, for the great job that they did this past week." Then he uttered the words that would launch hundreds of FCC complaints while capturing the way everyone living in Boston felt at the time: "This is our fucking city. And nobody gonna to dictate our freedom. Stay strong!"

It would be wrong for me to claim that the Boston Marathon bombing and the ensuing tragedy and triumph that it produced made me a Boston sports fan. But as I watched Big Papi speak, I began to realize that Boston was becoming home to me in ways Buffalo and Vegas never were. Boston sports had a huge hand in that, and I was grateful for the role they had in helping what has become my city heal.

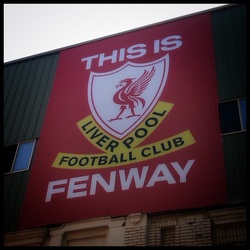

I don't know if Boston will always be where I live. But now when I leave the city, whether on vacation overseas or while visiting family and friends stateside, I take Boston with me; my love of the city and its sports teams reflected in the shirts and hats I bring along for the trip. When I travelled to England with my wife the summer after the bombing I purchased a Liverpool FC jersey in downtown Liverpool. With apologies to Hornby and Arsenal, I had decided to follow the Reds because of their connections to Boston via the Fenway Sports Group, and due to the thrilling experience of seeing them play at Fenway Park. And should I ever realize my dream of living in the UK, it will be “You’ll Never Walk Alone” coming from me on match days, with thoughts of Boston, whether I’m living in Merseyside or not.

Header image by T. Guzzio

CONNECT WITH TOM:

Here's the author and his lovely wife at a Red Sox game. In addition to editing Prodigal's Chair, Tom is a teacher, father, husband, writer, artist, futbol fan and slightly maladjusted optimist. He lives in Beverly, Massachusetts with his wife and their aging incontinent cocker spaniel, Honey (who approves this message). You can connect with him on Twitter @t_guzzio, or via email at [email protected].

ADD YOUR VOICE:

ABOUT COMMENTS:

At Prodigal's Chair, thoughtful, honest interaction with our readers is important to our site's success. That's why we use Disqus as our comment / moderation system. Yes, you will need to login to leave a comment - with either your existing Facebook, Twitter, or Google+ account - or you can create your own free Disqus account. We do this for a couple of reasons: 1) to discourage trolling, and 2) to discourage spamming. Please note that Disqus will never post anything to your social network accounts unless you authorize it to do so. Finally, if you prefer you can always email comments directly to us by clicking here.