What happens in Vegas may stay there, but it doesn’t go unnoticed. Nearly 40 million visitors a year make it their destination of choice for anonymous debauchery. Yet there are almost 2 million people living in the Las Vegas Metropolitan area. Believe it or not, their lives resemble the ones those 40 million Hangover extras return to once they’ve imbibed the decadence that greases the town’s neon gears.

I was one of those 2 million people.

In fact, I did something that many people outside of Vegas don’t think was possible: I grew up in Sin City. Now that I’ve been away, and have seen how people in so-called “normal” cities and towns live, I can reflect on how my experience as a kid was similar to and different from the ways kids in other parts of the country came up. It’s an interesting contrast, shaped not only by the town, but also by the times and my dysfunctional family. I don’t expect every person who grew up in Las Vegas to identify with what you’re about to read. Nor do I expect what I’ve written to be completely foreign to people who grew up in other places. With all that being acknowledged, I firmly believe that there’s something unique about being a child of The Meadows.

I was one of those 2 million people.

In fact, I did something that many people outside of Vegas don’t think was possible: I grew up in Sin City. Now that I’ve been away, and have seen how people in so-called “normal” cities and towns live, I can reflect on how my experience as a kid was similar to and different from the ways kids in other parts of the country came up. It’s an interesting contrast, shaped not only by the town, but also by the times and my dysfunctional family. I don’t expect every person who grew up in Las Vegas to identify with what you’re about to read. Nor do I expect what I’ve written to be completely foreign to people who grew up in other places. With all that being acknowledged, I firmly believe that there’s something unique about being a child of The Meadows.

THE MORE THINGS CHANGE...

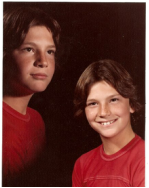

The author, circa 1978.

The author, circa 1978.

Something striking about Las Vegas to anyone who steps away from the Strip is the bizarre sameness of it all. Neighborhoods are marked by a level of consistency that can be mind-numbing. You drive on arterials that run through and around the town as the scenery zooms by in a repeating loop of apartments, tract houses, schools, mini-malls, and casino complexes – all awash in small streaks of neon and capped with Spanish tile. It’s the kind of cartoon sprawl that you could get lost in had the city not been planned out on a fairly predictable grid.

In 1976, as a five-year-old new to the city, I did get lost in the sameness. I had ventured out of our apartment complex for my first solo run to the 7-11 around the corner. I’d made the trip a few times before with my older brothers and sisters, and everything went along smoothly until I returned, Slurpee in hand, to my apartment, flung open the door, and found a completely strangers sitting in the living room watching TV. I dropped my Slurpee, took a deep breath, and pusjed aside my shock in convulsive sobs.

My complex was made up of a series of indistinguishable units that guarded both sides of the street. I turned into the courtyard for Building 4 when I should’ve been looking for Building 5, or something like that – I can’t remember the exact numbers – it all looked the same to me. The people whose afternoon I disrupted were kind and patient enough to help me get home. Maybe they were used to strange children opening their door. I can imagine the woman who helped me get to my apartment slowly getting up, sighing, and saying to the room more than to anyone particular person, “Another one? Really?”

In 1976, as a five-year-old new to the city, I did get lost in the sameness. I had ventured out of our apartment complex for my first solo run to the 7-11 around the corner. I’d made the trip a few times before with my older brothers and sisters, and everything went along smoothly until I returned, Slurpee in hand, to my apartment, flung open the door, and found a completely strangers sitting in the living room watching TV. I dropped my Slurpee, took a deep breath, and pusjed aside my shock in convulsive sobs.

My complex was made up of a series of indistinguishable units that guarded both sides of the street. I turned into the courtyard for Building 4 when I should’ve been looking for Building 5, or something like that – I can’t remember the exact numbers – it all looked the same to me. The people whose afternoon I disrupted were kind and patient enough to help me get home. Maybe they were used to strange children opening their door. I can imagine the woman who helped me get to my apartment slowly getting up, sighing, and saying to the room more than to anyone particular person, “Another one? Really?”

...THE MORE THINGS STAY THE SAME

The biggest constant during my years living in Las Vegas was the way the city was always changing. My family’s circumstances were such that I moved close to 20 times within the city before I graduated high school. That’s not typical regardless of where you live. My intransigence aside, there was, and continues to be, a massive demographic turbulence in Las Vegas that directly impacts how one experiences things like making and keeping friends – even if you're stationary.

When I graduated from Eldorado High School in 1989 (go Sundevils), there were – if I remember correctly – 11 high schools. Now there are over 30. The population has changed so dramatically that the number of high schools needed to serve the city has roughly tripled. Extrapolate back to the middle and elementary schools, and you have a lot of kids coming and going throughout the valley.

This growth continues to have an unsettling effect on anyone who stays in one place within Vegas for too long. Exact figures are hard to come by, but it’s known that for all of the people moving into the city each month, there is a smaller, yet significant number of people moving out. Many of the relationships I made in Vegas were literally built on shifting sands. The desert where you rode your bikes and went hunting for lizards gave way to new developments with new schools that siphoned off students you got used to riding the bus with because, even though they lived just the next block over they were suddenly zoned for a different school. I remember there being times when classes were consolidated midway through the year because so many kids had moved, and other times when new classes were created to accommodate sudden growth. People were coming and going all the time. My family’s dysfunction – parents divorcing, older siblings leaving, the constant moving in and around the city – made me a fairly depressed, solitary kid. The fact that I was depressed and solitary in an a demographically amorphous town made things worse. A plant needs strong roots to thrive in the desert.

When I graduated from Eldorado High School in 1989 (go Sundevils), there were – if I remember correctly – 11 high schools. Now there are over 30. The population has changed so dramatically that the number of high schools needed to serve the city has roughly tripled. Extrapolate back to the middle and elementary schools, and you have a lot of kids coming and going throughout the valley.

This growth continues to have an unsettling effect on anyone who stays in one place within Vegas for too long. Exact figures are hard to come by, but it’s known that for all of the people moving into the city each month, there is a smaller, yet significant number of people moving out. Many of the relationships I made in Vegas were literally built on shifting sands. The desert where you rode your bikes and went hunting for lizards gave way to new developments with new schools that siphoned off students you got used to riding the bus with because, even though they lived just the next block over they were suddenly zoned for a different school. I remember there being times when classes were consolidated midway through the year because so many kids had moved, and other times when new classes were created to accommodate sudden growth. People were coming and going all the time. My family’s dysfunction – parents divorcing, older siblings leaving, the constant moving in and around the city – made me a fairly depressed, solitary kid. The fact that I was depressed and solitary in an a demographically amorphous town made things worse. A plant needs strong roots to thrive in the desert.

LIFE ON MARS

Not the skyline one normally associates with Las Vegas. Photo by the author.

Not the skyline one normally associates with Las Vegas. Photo by the author.

Growing up in the desert was also a gift. The land was wild, dusty, and alive. I made it my playground. My first dog – my best friend during the lonely years after my family disintegrated – came to me from a wild pack, an instant bond as like recognized like.

He wasn’t my only gift from the desert.

After my mom and her new boyfriend (who would eventually become my step-father) fought mom would take my brother and me out to Valley of Fire, or Red Rock Canyon, or to Lake Mead. Free from a house filled with stress and tension, my brother and I scrambled over rocks chasing lizards – something we also did in the patches of desert around wherever we happened to be living at the time. Yet to be developed scrub lots were also part of the formula of sameness in Vegas, and we made Secret Gardens among the snakes, scorpions, abandoned mine shafts, bomb shelters, vagrants, and piles of illegally dumped trash.

It’s surreal how intermingled desert, housing, and casinos were to the boy I was, the boundaries broken by my not knowing any better. When I was about 9 my brother, some friends, and I headed into the desert looking for a good place to ride bikes. We often carved BMX tracks out of the dirt, built jumps and berms. We used old tires and other trash to mark out the corners. That day we lazily rode up and down the sides of a concrete culvert designed to catch heavy late summer rains, and we decided to follow it for as far as we could. A thunderstorm might have washed us away, something that still happens from time to time. Instead we came to a tunnel, moved past the homeless people camped near its entrance, and moved down into the darkness. We hoped there would be sunlight at the other end eventually, and behold, we came out near the Strip. Soon I was riding my bike around the fountains outside of Caesar’s Palace like a pint-sized Evil Knievel. I think there were five or six of us, ranging from ages 8 to 12.

A beautiful moment came in January of 1979, when seven inches of snow blanketed the valley and shut down the town. I walked to the desert, got down on my hands and knees in the frosted dirt and gravel for a lizard's-eye view of the sage and creosote now flocked in white. I lay down in the muffled silence created by the fallen snow and wondered what a hibernating whiptail would think if it woke up to this winter wonderland.

He wasn’t my only gift from the desert.

After my mom and her new boyfriend (who would eventually become my step-father) fought mom would take my brother and me out to Valley of Fire, or Red Rock Canyon, or to Lake Mead. Free from a house filled with stress and tension, my brother and I scrambled over rocks chasing lizards – something we also did in the patches of desert around wherever we happened to be living at the time. Yet to be developed scrub lots were also part of the formula of sameness in Vegas, and we made Secret Gardens among the snakes, scorpions, abandoned mine shafts, bomb shelters, vagrants, and piles of illegally dumped trash.

It’s surreal how intermingled desert, housing, and casinos were to the boy I was, the boundaries broken by my not knowing any better. When I was about 9 my brother, some friends, and I headed into the desert looking for a good place to ride bikes. We often carved BMX tracks out of the dirt, built jumps and berms. We used old tires and other trash to mark out the corners. That day we lazily rode up and down the sides of a concrete culvert designed to catch heavy late summer rains, and we decided to follow it for as far as we could. A thunderstorm might have washed us away, something that still happens from time to time. Instead we came to a tunnel, moved past the homeless people camped near its entrance, and moved down into the darkness. We hoped there would be sunlight at the other end eventually, and behold, we came out near the Strip. Soon I was riding my bike around the fountains outside of Caesar’s Palace like a pint-sized Evil Knievel. I think there were five or six of us, ranging from ages 8 to 12.

A beautiful moment came in January of 1979, when seven inches of snow blanketed the valley and shut down the town. I walked to the desert, got down on my hands and knees in the frosted dirt and gravel for a lizard's-eye view of the sage and creosote now flocked in white. I lay down in the muffled silence created by the fallen snow and wondered what a hibernating whiptail would think if it woke up to this winter wonderland.

"I SEE LONDON, I SEE SAM'S TOWN"

Iconic Circus Circus sign. Photo: Mutari.

Iconic Circus Circus sign. Photo: Mutari.

There are things people who didn’t grow up in Las Vegas ask people who did: “Was your mom a showgirl?” or, “Did you gamble all the time?” No, my mother was not a showgirl. And, no, I didn’t gamble all the time because it’s illegal unless you’re 21. But casinos played a definitive part of my life growing up, and I doubt it’s that different for kids in Vegas today.

As a teen, me and a few buddies would go trolling for suckers – and girls – at the midway in Circus Circus. We had a system for making extra money at the quarter-toss, that carnival game where if you managed to land a quarter on a crystal plate, you’d win a huge stuffed animal. We’d take turns lobbing stacks of five quarters at once, before they changed the rules and made it so you could only throw one quarter at a time. The bottom quarter always stuck, and we’d stroll around the midway carrying the tacky stuffed animals on our shoulders (they were that big), and chat up girls before we'd loop back to the game. Inevitably, there’d be some poor sap trying to win a toy for his girl or his kid. We’d wait until he tossed away few dollars worth of quarters, and then offer him our bounty for ten bucks. If we got hungry, a cheap meal wasn't far away, because you could always get a dollar foot-long at the Slots-O'-Fun next door.

Eventually, spending time on the Strip grew less appealing because, frankly, we weren't wanted there. The city placed a Strip-specific curfew for minors. But a trend started during my high school years that offered teens an alternative. This was the growth of so-called “locals” casinos that began popping up all over the valley, so much so that they soon became part of the aforementioned Vegas sameness. These were places that captured more revenue from residents as opposed to tourists. They had all of the things you’d expect from casinos – hotel rooms, video and table games, sports books, restaurants and lounges – along with things you’d expect to find in “normal” neighborhoods like movie theaters, fast food restaurants, and bowling alleys. Some even had ice rinks.

Palace Station was probably the first such complex, followed by Sam's Town, but the real game-changer for me was the Gold Coast Hotel and Casino, which opened in 1986. I was a sophomore in high school, and my friends and I would go there to bowl, see movies, and just hang out. This isn’t to say we didn’t hang out in other places, too. Vegas had its share of malls and parks, but we couldn't get a $3.00 steak dinner at two in the morning at the park (at least not a good one).

These local entertainment complexes began to elbow out other stand-alone establishments. Why would you go see a movie in a broken down theater when you could see it at the brand new one – with surround sound, no less – that just happened to be in a casino? You could make a day of it - eat at the buffet afterwards, then go bowl a few frames while the parents played some video poker. Everything you needed entertainment-wise – regardless of your age – was in one place.

All of this was just normal to me. It wasn't until I left for college that I first began to realize how growing up in a place most people only come to visit might have been unusual. I attended Ohio University, in Athens – a decidedly different place – about an hour south of Columbus. I couldn’t sleep those first few weeks in Athens, because at night it was too dark, too quiet. The methadone for my Vegas withdrawals became midnight trips to the 24-hour Kroger, where I'd vacantly push around an empty shopping cart, the fluorescent lights making a poor neon substitute. Eventually I got a sound machine and slept much better.

As a teen, me and a few buddies would go trolling for suckers – and girls – at the midway in Circus Circus. We had a system for making extra money at the quarter-toss, that carnival game where if you managed to land a quarter on a crystal plate, you’d win a huge stuffed animal. We’d take turns lobbing stacks of five quarters at once, before they changed the rules and made it so you could only throw one quarter at a time. The bottom quarter always stuck, and we’d stroll around the midway carrying the tacky stuffed animals on our shoulders (they were that big), and chat up girls before we'd loop back to the game. Inevitably, there’d be some poor sap trying to win a toy for his girl or his kid. We’d wait until he tossed away few dollars worth of quarters, and then offer him our bounty for ten bucks. If we got hungry, a cheap meal wasn't far away, because you could always get a dollar foot-long at the Slots-O'-Fun next door.

Eventually, spending time on the Strip grew less appealing because, frankly, we weren't wanted there. The city placed a Strip-specific curfew for minors. But a trend started during my high school years that offered teens an alternative. This was the growth of so-called “locals” casinos that began popping up all over the valley, so much so that they soon became part of the aforementioned Vegas sameness. These were places that captured more revenue from residents as opposed to tourists. They had all of the things you’d expect from casinos – hotel rooms, video and table games, sports books, restaurants and lounges – along with things you’d expect to find in “normal” neighborhoods like movie theaters, fast food restaurants, and bowling alleys. Some even had ice rinks.

Palace Station was probably the first such complex, followed by Sam's Town, but the real game-changer for me was the Gold Coast Hotel and Casino, which opened in 1986. I was a sophomore in high school, and my friends and I would go there to bowl, see movies, and just hang out. This isn’t to say we didn’t hang out in other places, too. Vegas had its share of malls and parks, but we couldn't get a $3.00 steak dinner at two in the morning at the park (at least not a good one).

These local entertainment complexes began to elbow out other stand-alone establishments. Why would you go see a movie in a broken down theater when you could see it at the brand new one – with surround sound, no less – that just happened to be in a casino? You could make a day of it - eat at the buffet afterwards, then go bowl a few frames while the parents played some video poker. Everything you needed entertainment-wise – regardless of your age – was in one place.

All of this was just normal to me. It wasn't until I left for college that I first began to realize how growing up in a place most people only come to visit might have been unusual. I attended Ohio University, in Athens – a decidedly different place – about an hour south of Columbus. I couldn’t sleep those first few weeks in Athens, because at night it was too dark, too quiet. The methadone for my Vegas withdrawals became midnight trips to the 24-hour Kroger, where I'd vacantly push around an empty shopping cart, the fluorescent lights making a poor neon substitute. Eventually I got a sound machine and slept much better.

THE PATRON SAINT OF GAMBLERS

Photo: USA Today

Photo: USA Today

More than anything else, the thing about Las Vegas that has come to define the person I am was church. Depending on the data you use, Las Vegas may or may not boast more churches per capita than any other US city. On one level this makes perfect sense. If you have a town full of Saturday sinners, you’ll need a lot of room for Sunday saints. As much as I’d like to blame my family’s dysfunction on Sin City, the truth is that moving to Vegas was a band-aid on the head wound that caused my family’s death. There are many, many families in Las Vegas that are whole – stereotypically so – but we were not among them. Vegas draws many desperate people like my parents, who want better for themselves and their kids, but who end up seeing the town as a broken place.

On top of that, there is no end to the people coming and going who are determined to save the people of Sin City. Las Vegas is a mecca for vice. Gambling is not only legal, it’s celebrated, pays for the schools, and makes it possible for the state to collect no income tax. While prostitution is technically illegal, brothels in nearby counties will pick up any customer in need of the services they offer, and you need only walk down the Strip to know that “escorts” are readily available, and will come “direct to you” because there’s billboards on wheels, and a bunch of skeevy guys passing out handbills that say so.

My brother and I – with the sanction of our parents and some help from the state – wound up involved with some Jesus People, and it probably saved our lives, if not our souls. Michael, my brother, who is older by two-and-a-half years, did something stupid. A kid who just moved into the neighborhood (one of the longest we had lived in at roughly three years) thought it would be good to make friends by sharing his dad’s pot. Mike was in seventh grade; and, well, he liked pot. He and an older boy went to this kid’s house, only to find no one home and the door slightly ajar. They went in, looked around a bit, opened some drawers, found a few bucks and a few joints, and left. Then they headed for the local arcade (this was 1982-ish – Pac Man Fever was is full flush), and bragged about their little adventure. Someone else then went back to said house and ransacked the place. Guess who got the blame?

Here’s where it gets strange. The owner of the home initially went to the police, but later refused to press charges because Mike had found pot. How would that look in court? “Yes, your Honor, that looks like my weed.” Mike and I had been running wild all over the neighborhood, especially during the summer, when we were on our own until our parents got home from work. We sniffed gas. We jumped off our roof and into our pool, mooning cars on the way down. We sold parsley to younger kids and called it pot. We shot bottle rockets at each other. By this point, my mother and stepfather had enough of my brother’s behavior. They blamed him for both his actions and mine, citing him as a bad influence on me even though I willingly went along for the ride in the cars we stole. They did the most responsible bit of parenting they ever did: turned my brother over to the state as an unmanageable child.

After a few weeks in juvie, Mike was placed in a Christian run youth home called Mizpah House. It was probably the best thing that could have happened to us. The person who ran the program was a Cuban refugee whose father was killed by the Castro regime / former outlaw biker / former drug dealer named Jose Boveda. Looking back, it’s clear he was a zealot who saw proselytizing as his job, but it was also clear that, at least for a time – a crucial time – he greatly and sincerely cared for my brother and me. Jose wanted us to be better people, to not make the mistakes he made, and he helped us do that by giving us better things to do. Going to church, in my mind, was a small price to pay for learning martial arts, taking trips to Disneyland, going camping in Colorado, or hiking in the red mountains of my precious desert. If I spent my elementary years raising the hell I should have done in high school, I made up for it by spending my high school years in church. From 10 to 18, Jose and the people at Mizpah would be my stable family. They would guide me through my first love and first heartbreak. They became a constant as the latest version of my biological family continued to ricochet across the valley.

There’s a story as to how that family too fell apart – a good one, full of rebellion and pain – just like most coming of age tales. But the take away as it applies to growing up in Las Vegas is that, when I most needed to, I found an unlikely sort of salvation in Sin City.

On top of that, there is no end to the people coming and going who are determined to save the people of Sin City. Las Vegas is a mecca for vice. Gambling is not only legal, it’s celebrated, pays for the schools, and makes it possible for the state to collect no income tax. While prostitution is technically illegal, brothels in nearby counties will pick up any customer in need of the services they offer, and you need only walk down the Strip to know that “escorts” are readily available, and will come “direct to you” because there’s billboards on wheels, and a bunch of skeevy guys passing out handbills that say so.

My brother and I – with the sanction of our parents and some help from the state – wound up involved with some Jesus People, and it probably saved our lives, if not our souls. Michael, my brother, who is older by two-and-a-half years, did something stupid. A kid who just moved into the neighborhood (one of the longest we had lived in at roughly three years) thought it would be good to make friends by sharing his dad’s pot. Mike was in seventh grade; and, well, he liked pot. He and an older boy went to this kid’s house, only to find no one home and the door slightly ajar. They went in, looked around a bit, opened some drawers, found a few bucks and a few joints, and left. Then they headed for the local arcade (this was 1982-ish – Pac Man Fever was is full flush), and bragged about their little adventure. Someone else then went back to said house and ransacked the place. Guess who got the blame?

Here’s where it gets strange. The owner of the home initially went to the police, but later refused to press charges because Mike had found pot. How would that look in court? “Yes, your Honor, that looks like my weed.” Mike and I had been running wild all over the neighborhood, especially during the summer, when we were on our own until our parents got home from work. We sniffed gas. We jumped off our roof and into our pool, mooning cars on the way down. We sold parsley to younger kids and called it pot. We shot bottle rockets at each other. By this point, my mother and stepfather had enough of my brother’s behavior. They blamed him for both his actions and mine, citing him as a bad influence on me even though I willingly went along for the ride in the cars we stole. They did the most responsible bit of parenting they ever did: turned my brother over to the state as an unmanageable child.

After a few weeks in juvie, Mike was placed in a Christian run youth home called Mizpah House. It was probably the best thing that could have happened to us. The person who ran the program was a Cuban refugee whose father was killed by the Castro regime / former outlaw biker / former drug dealer named Jose Boveda. Looking back, it’s clear he was a zealot who saw proselytizing as his job, but it was also clear that, at least for a time – a crucial time – he greatly and sincerely cared for my brother and me. Jose wanted us to be better people, to not make the mistakes he made, and he helped us do that by giving us better things to do. Going to church, in my mind, was a small price to pay for learning martial arts, taking trips to Disneyland, going camping in Colorado, or hiking in the red mountains of my precious desert. If I spent my elementary years raising the hell I should have done in high school, I made up for it by spending my high school years in church. From 10 to 18, Jose and the people at Mizpah would be my stable family. They would guide me through my first love and first heartbreak. They became a constant as the latest version of my biological family continued to ricochet across the valley.

There’s a story as to how that family too fell apart – a good one, full of rebellion and pain – just like most coming of age tales. But the take away as it applies to growing up in Las Vegas is that, when I most needed to, I found an unlikely sort of salvation in Sin City.

IT'S A NICE PLACE TO VISIT

Postcard from the National Atomic Testing Museum, via the author.

Postcard from the National Atomic Testing Museum, via the author.

42 million people go through the Las Vegas Valley each year. 40 million of them call someplace else home. You hear stories about encounters residents have with tourists, like the time a woman commented to a friend’s mom how nice it was for the casino to fly her in for work. As was the custom back in the day, casino workers wore where they were from on their name tags, so that my friend’s mom’s said, “Lynn, from California.” The tourist couldn’t conceive that Lynn, like tons of other people, actually lived in Las Vegas. She thought the casino bosses flew Lynn out, and put her up in the hotel.

No shit.

But that happened in the late 70s, when Vegas really was a small place.

It still seems small to me, though I’m sure it’s changed dramatically since I was there last – to visit my mom in 2007. Then, I eased into the town like a well-worn pair of jeans, seeing old familiar touchstones hidden beneath the new veneer. I’ve no doubt that the familiar beat and pulse of the town remains the same, despite the Ferris Wheel, and the Golden Knights, and the coming of the Raiders. I talk about going back to visit – bringing my wife who has never been, and showing her places that make up this story, as well as other places off the beaten path, like the Atomic Testing Museum. I know that, even through the recession, the town continued to sprout and grow, pushing my desert further and further out, making neighborhoods of the desolate places I once built forts in. Regardless of how much the city has or hasn’t changed, I know that I will never be lost in Las Vegas, just as surely as I know that I will never live there again, even though I still call it “home.”

No shit.

But that happened in the late 70s, when Vegas really was a small place.

It still seems small to me, though I’m sure it’s changed dramatically since I was there last – to visit my mom in 2007. Then, I eased into the town like a well-worn pair of jeans, seeing old familiar touchstones hidden beneath the new veneer. I’ve no doubt that the familiar beat and pulse of the town remains the same, despite the Ferris Wheel, and the Golden Knights, and the coming of the Raiders. I talk about going back to visit – bringing my wife who has never been, and showing her places that make up this story, as well as other places off the beaten path, like the Atomic Testing Museum. I know that, even through the recession, the town continued to sprout and grow, pushing my desert further and further out, making neighborhoods of the desolate places I once built forts in. Regardless of how much the city has or hasn’t changed, I know that I will never be lost in Las Vegas, just as surely as I know that I will never live there again, even though I still call it “home.”

Header art by T. Guzzio. Original photo via Wikimedia Commons.

CONNECT WITH TOM:

In addition to editing Prodigal's Chair, Tom is a teacher, father, husband, writer, artist, futbol fan and slightly maladjusted optimist. He lives in Beverly, Massachusetts with his wife and their cocker spaniel, Honey (who approves this message). You can connect with him on Twitter @t_guzzio, or via email at [email protected].

ADD YOUR VOICE:

ABOUT COMMENTS:

At Prodigal's Chair, thoughtful, honest interaction with our readers is important to our site's success. That's why we use Disqus as our comment / moderation system. Yes, you will need to login to leave a comment - with either your existing Facebook, Twitter, or Google+ account - or you can create your own free Disqus account. We do this for a couple of reasons: 1) to discourage trolling, and 2) to discourage spamming. Please note that Disqus will never post anything to your social network accounts unless you authorize it to do so. Finally, if you prefer you can always email comments directly to us by clicking here.